Facilitating Reflection on Year Abroad Learning - Digital media and Portfolio Module

Siobhan Mortell

Department of German, University College Cork

BACKGROUND

The Department of German at University College Cork has three international programmes, including the BComm International, for which I coordinate the Year Abroad. All students going abroad do so during their third year of study, are required to spend two semesters in Germany/Austria, and take a mix of courses in language and business, as well as one literature/culture module. They are also given the option of completing a tandem learning module, and a portfolio module, as presented in this paper. The Department of German offers two preparatory modules for year abroad during their second year, of which students may choose one, and of which neither is compulsory. One of these deals with postwar history and culture (Political and Social Culture since 1945), the other with intercultural learning (An Intercultural Journey: Preparation and Reflective Writing for the Year Abroad). Students are guided by their respective coordinators with regard to processes and bureaucracy before departure, and are given a handbook outlining academic requirements, timelines, some guidance on how choose courses, doing a work placement, housing, and much more. All students on international programmes must spend two semesters abroad, and some of them have the option of doing a work placement in their second semester, which they organise in liaison with staff of the department.

INTRODUCTION

Everyone who works on Year Abroad matters knows what a transformational experience it can be. Students themselves, however, often seem unaware of what benefits they have gained or cannot articulate these. When asked in class on return what benefits the year abroad brought, common answers are making friends from many countries, travel, and language improvement. While these are all worthwhile outcomes in themselves, over several years, the students I asked seemed unable to reflect on any deeper learning from their year abroad. Based on these observations, I designed a portfolio module consisting of five mostly reflective tasks which require students to present these reflections using different forms of digital media, such as blog, online magazine, or animation, among others. Students complete this module during their time abroad. I piloted this module with 21 participants in 2017-18, 15 participants in 2018-19, and four participants in 2019-20.

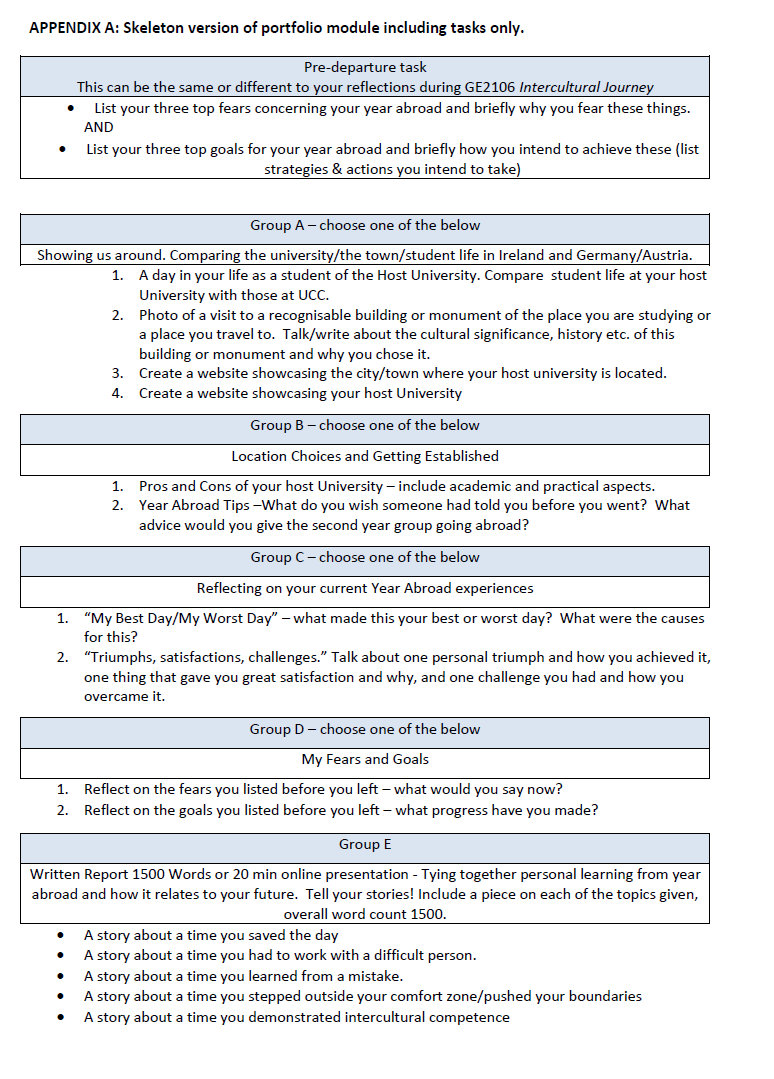

The portfolio module is optional. Students are sent all tasks in one attachment to an email before they leave or very early during their study abroad. Submission dates are spread across the academic year from November to July and the five tasks (see Appendix A) are timed so that students have experienced enough to engage in meaningful reflection for them. For example, the third task, with a submission date in the spring, requires reflecting on the pre-departure goals and fears when they have already completed a full semester and settled in their location and university. Each task has a choice of at least two options, of which students choose one. In the first two runs of this module, submission was done via a shared folder in google docs. Subsequently, due to GDPR concerns, each student now submits to a folder in google docs which is shared only between the student and the lecturer. This module is graded on a pass/fail basis only. Given the reflective nature of tasks and the fact that they are based on individual experience and can therefore sometimes be very personal, I look for appropriate length and level of reflection in deciding on pass/fail. The module has five main aims. The first is to capture information for outgoing students that is often lost. The second is to encourage and enable deeper and more structured reflection on their learning from their time abroad. Graduates consistently report informally that in job interviews, selection panels often spent more time probing the graduate’s year abroad experience than anything else. This led to the third aim of exploring the year abroad experience with reference to their future professional life. A fourth aim was born of the awareness that people express themselves differently in different media (using words, images, sound, etc.) and that digital skills are increasingly important in today’s world. A fifth aim developed after the completion of the first module run when it became clear that students found it useful to look back at their pre-departure fears and goals.

In some cases, students’ work far exceeded expectations and the best examples of student work are disarming in their honesty and self-awareness, and are often beautifully done. They have opened my eyes to new facets of the students themselves and have reinforced for me the enormous benefits of study abroad. It has been satisfying to see students progress in their personal development, reflect on their experience, and to see them become aware of their own individual progress also. Feedback from students has, to date, been largely positive. Minor issues have arisen in terms of the organisation of the module and clarity of instruction, but these have been easily resolved.

While the module was created for language students, it can be applied in any context, for example people who spend time in foreign locations but where their home language is spoken (e.g. Irish students studying science in Australia). Equally, it could be given to young people going abroad as an au-pair or teaching assistant, or any other longer stay in a foreign environment, irrespective of language.

FIVE AIMS

1. Capturing location-specific information for future students

Since 2002 I have been coordinating the Year Abroad for students of Commerce with German at University College Cork. This includes allocating places at host universities, practical aspects of preparing them for study abroad, for example giving information on the types of teaching offered at their host university (lecture, seminar, tutorial) and guidelines on choosing courses for their year abroad. It also includes monitoring them while abroad, and the examinations and approval process at their home university on return. In preparing them and allocating places, I have listened to the questions outgoing students ask, the worries they have about their study abroad, and the kind of information they feel they need before departure. In addition, I have listened to returned students informally report on their study abroad experience, and comment on these. It became clear that useful, sometimes even crucial information bypasses me as a staff member. Tips about specific locations as well as general year abroad tips are usually lost when students leave university without passing it on to outgoing students. Whether this is passed on seems purely coincidental. What gets lost is information, along with the benefits this may bring for future outgoing students, and includes information such as in which locations it might be easier to find part-time work (useful for students with financial pressures), or how to deal with a multiplicity of complex methods of registration for academic modules at host universities (saving a lot of stress during an already pressured initial settling in period).

With this in mind, one of several aims of this portfolio module is to capture information for future students going abroad using tasks that require them to introduce the reader/listener to their location or university (task A) and give tips on how to make the most of the year abroad experience, or compare their home institution with the host institution (task B). An example of Task A work submitted has been depicting a day in the life of the student at their host university, using film or cartoon media. Other students have given a tour of the town or city using photographs with text, or by creating a blog. (see appendix C for an example of student work for this task). Still others have described a central monument or feature of the city or area and its significance using photographs or film. Examples of Task B work submitted has included film, blogs, audio and text, and included topics such as overcoming fears and making friends. (see appendix B for an example of student work for this task) Much of the information captured to date has already been made available to outgoing students, with the consent of the students whose work is being shared. Consent comes in the form of an opt-out given in the module description. For a limited period outgoing students are given read-only access to a shared folder in google docs containing this information. By collecting information from former Year Abroad students and making it available, current outgoing students can read and digest this, which may help to allay any fears (Li, Olson and Frieze, 2013) they may have and give them tools to plan their experience and gain more benefit.

2. Encouraging deeper reflection on year abroad experience and benefits

The main aim of this module is to enable and encourage a deeper reflection on students’ year abroad learning experience. In constructing the tasks for the module, I was interested in what their challenges were, how they overcame these, what they learned about themselves, and why this is of value. By reflecting and writing not after they returned (and probably through rose-tinted glasses), but as they were going through the year, in the process of coping with challenging times while settling in, my aim was to make them more aware of the personal development they were gaining through their experiences abroad, and which immediate as well as future benefits these were bringing.

Knowing ahead of time what each task requires them to think about, participants had to filter their experiences day by day. For example, one option for task C requires them to reflect on ‘triumphs, satisfactions, challenges,’ for which submission is in Spring following the first semester spent abroad, thus giving them time to settle at the university and the location, complete initial bureaucracy, get to grips somewhat with the living language, make friends and live one semester of student life in a different country. For this they had to monitor their experiences each and every day, and consider what personal triumph, satisfaction, challenge meant for them, and why. For one student, it was a triumph to master using the washing machine, for another it was to pass a difficult exam. For one student satisfaction meant seeing incremental improvements in language and communication skills, for another, it meant standing their ground in a discussion in the foreign language. For one student, challenge meant overcoming homesickness, for another it meant explaining to the doctor what ailed them. In thinking about what they had experienced, deciding what these triumphs, satisfactions, and challenges meant in their lives and describing these in words for another person, students have told me they became aware of how far they had come in only a few months. The benefits became more tangible to the students.

Another option for task C requires them to reflect on their best or their worst day. In completing this task, students had to first consider what a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ day meant for them, monitor their experiences of good and bad, and then choose the best or worst of these. One student, for example, made a very poignant and beautiful four-minute film about her worst days, which for her were all the days when she had to say goodbye to the friends she had made. Another student wrote a longer text as a blog entry with photographs. She described spending a day visiting a rural Italian vineyard owned by the family of a friend she had made and weeping hysterically on the seven-hour bus ride home, overwhelmed by the beauty and simplicity of her experience.

3. Learning for future professional life and career

A third aim is to relate personal development during study abroad to future professional life, specifically, skills students can relate in a job interview, such as learning from mistakes, communication, intercultural competence (of lack thereof), or problem solving. For this task (task E) one student, when writing about learning from a mistake, realised that being abroad had taught her to:

put aside pride and ignorance and open up more to the fact that I don’t actually always know everything. I’m definitely much more likely to seek guidance or help now - that’s why we are given academic coordinators and mentors, after all. (Student 34, Year Abroad 2018-19)

Another student, writing about intercultural competence for the same task, described a project team situation where she gave polite instructions to local students using (English) language commonly used for this in English-speaking cultures, but which was not interpreted as an instruction by the local students. This led to some confusion and some adjustments to the assignment not being completed. (Student 33, Year Abroad 2018-19)

4. Overcoming fears and achieving goals in a study abroad period

Students’ entries to task D clearly show that pre-departure fears such as homesickness, not being able to understand or be understood, not making friends and social isolation are common. Goals for the year abroad frequently include travel and improving language skills. However, strategies to overcome fears and achieve desired goals are consistently vague. Having read these perceived fears and potential goals, I wanted to support students, and thus the fourth aim of this module became the capturing of information which can potentially be used to help future outgoing students streamline their strategies in both areas (overcoming fears and achieving goals) and make them more concrete and achievable. Students were asked to articulate their fears and goals before they depart for the host university and reflect on them once more the following spring. One student, who had been neither particularly confident nor struggled with the idea of going abroad, in hindsight, described her fears as ‘faintly laughable’, and expresses part of her progress as follows:

Reliance breeds complacency and unfortunately before this year, while I would have always viewed myself as an independent person, I rarely planned or organized myself enough to back up this assumption. However, I feel as though I have acquired maturity through some rather steep learning curves, which stemmed from coordinating my various college modules into a complementary timetable, navigating life in another country and travelling. (Student 23, Year Abroad 2018-19)

Other students expressed similar sentiments. They felt that reflecting at a later point enabled them to see the progress they had made and found this very satisfying.

5. Developing digital media skills

The final aim is to facilitate the development of new skills in the digital area, as well as creativity in presenting the information and reflections. The five tasks in the module challenge the students to explore unfamiliar digital media such as writing a blog, creating a website or an online magazine, or using video or animation. Students are given some media options, but they are not limited to these. To date they have used variations on all the above. They are not given lists of specific tools, nor any training in digital skills. The results have been mixed. For example, some students put immense thought and preparation into creating a film or animation that appropriately reflects their thoughts and experience: backdrop, music, choosing and sequencing clips, subtitles, voiceover. Others put more into the reflection itself and less into the presentation of it.

PORTFOLIO MODULE AS A FRAMEWORK FOR REFLECTION ON YEAR ABROAD LEARNING

This module provides students with a framework by which to structure their reflections on their experiences and consequently their personal development. In my experience, general questions (What was the high point/low point of the year? What would you change if you could?) tend to elicit general answers and all students experience significant personal development during this time, but participants doing this module answer very specific questions aimed at making their development more visible to them.

STUDENT FEEDBACK ON THE PORTFOLIO MODULE

Feedback was gathered anonymously from one group (2018-19) after completion of the module and using google forms. Participants answered two questions, namely, what benefits they saw and how the module could be improved. Of the 15 who completed the module, 12 responded. In the feedback, students mentioned the following benefits: tracking progression, reflecting on mistakes and learning for the future, recording experiences (a form of journal), benefit to future students, and that it served as a series of marking points for their time abroad. Suggestions for improvement included different/later submission dates, answering in the foreign language, more emphasis on using different media, more on ‘what we had learned from the year, in terms of developing ourselves personally as well as our notable improvement in language proficiency.’ (anonymous feedback 2018-2019)

BENEFITS AND AMENDMENTS TO PORTFOLIO MODULE

In the absence of more structured research on its outcomes, the module appears to enable deeper reflection on development and learning during study abroad, as well as increasing media competence to a degree. It also appears to generate higher awareness of one’s own experience and the processing of it. Insight gained from portfolio entries and feedback can be used to better prepare outgoing students so they can avoid pitfalls and benefit more and sooner from the study abroad. Students have displayed what I consider to be significant talent and creativity, for example photography, film making and animation, writing and humour, introspection, and charisma in front of the camera. Minor problems have arisen in terms of file compatibility and features being lost. One group of students tended to type all their entries into a word document and seemed to dispense with media creativity, although feedback indicated that instructions were not clear. How to organise submission of portfolio entries has required some thought, as uploading to a common folder (google docs) to which all participants have access may lead to privacy and GDPR issues. However, students have said they enjoyed reading what their peers were experiencing and this would be eliminated by not sharing. Using a shared folder, I had also wondered whether copying from peers whose entries they had had temporary access to would be an issue, but this did not appear to be the case. They did, however, seem to get inspiration from each other concerning media for future entries.

INTEGRATING LEARNING FROM THE PORTFOLIO INTO YEAR ABROAD PREPARATION AND THE WIDER CURRICULUM

There is a clear need for gathering more structured and detailed feedback, as well as finding a way to measure the benefit and learning from the portfolio module. This could be compared to those who studied abroad without completing the module. Insights could be fed into improving the module itself and year abroad preparation work. Another area could look at translating student reflections on year abroad experiences into concrete insights into where each student progressed in their development, e.g. became a better communicator etc., and how this is of value (DeGraaf et.al., 2013).

It is possible that realisation of the real benefits and learning of such experiences as the year abroad come only later. One could potentially gather feedback from participants three to five years after completion and develop this. The insights into fears, goals and strategies around these could be used to construct a pre-departure workshop, encouraging students to think them through more carefully, streamline them, and facilitate students to begin operating more ‘effectively’ at an earlier point during their study abroad. Students could then potentially go further towards achieving the goals they set for themselves. Finally, future research could analyse whether the information captured by previous students and made accessible to outgoing students is of use to outgoing students.

REFLECTIONS ON THE PORTFOLIO MODULE IN ITS CURRENT FORM

One study found that ‘many students felt they increased their confidence, gained independence, matured and became stronger persons through overcoming challenges’ (Meyer, 2010, p.46). Part of becoming stronger, more confident, and more mature is working through one’s fears and learning that one can in fact get through difficult situations, they are perhaps not as difficult to overcome as one thought, and that one has (or can develop) personal resources to do this. Another part of this might lie in the achievement of one’s goals, or the realisation that the goals needed adjustment, or the strategies one had set out to achieve them needed more thought. Perhaps fears about study abroad can never fully be allayed without going through the experience in person, but if progress can be made visible to students through reflecting on fears and goals from before departure, the satisfaction this can bring could be considered one of positive outcomes of the module.

It is also possible that some of these aims are not achievable – one student, when asked informally what she would change if she had her time again, said: ‘Nothing. It was imperfect, but I wouldn’t change any of it.’ (Student 32, Year Abroad 2018-19) The courage to accept imperfection is a valuable lesson indeed, and one which outgoing students and those who prepare them could often benefit from.

Address for correspondence: s.mortell@ucc.ie

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DeGraaf, D., Slagter, C., Larsen, K. and Ditta, E. 2013. the long-term personal and professional impacts of participating in study abroad programs. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 23(1), pp.42-59.

Li, M., Olson, J.E. and Frieze, I.H. 2013. Students' study abroad plans: the influence of motivational and personality factors. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 23, pp.73-89.

Meier, G. 2010.Review of the assessment of the year abroad in the modern language degrees at Bath: Assessment for experiential and autonomous learning based on the continuity model Research Report University of Bath.

Williams, T.R., 2017. Using a PRISM for reflecting: providing tools for study abroad students to increase their intercultural competence. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 29(2), pp.18-34.