Communicating issues of students in relation to mental health and identifying blind spots of support networks of year abroad

Takako Amano

Department of Japanese Studies, School of Humanities, Language and Global Studies, University of Central Lancashire, UK

ABSTRACT

This study identifies students’ mental health issues that are unique to the year/study/period[1] abroad programme to start and it draws attention to the interchangeably used terms that refer to mental health related concerns. By employing on-line corpora, it carries out quantitative analyses of terms used when mental health related issues are communicated between 1991-1994 mainly in Britain and as of 2017 in various Englishes. Based on these corpus analyses, not only the mostly used and diminishing terms but also emerging terms are identified. Whilst mental illness remains the most used term over the decades, it is found that mental health issue/s and anxiety disorder/s are rapidly increasing their usages. The study further explores mental health crisis/crises, the third fast growing term in terms of their usages, in the context of period abroad. Based on the clinical definition by the Joint commissioning panel for mental health (JCPMH), it examines the support network of students abroad who face mental health crises by suggesting a worksheet, which analyses the roles of period abroad coordinators and support staff of both home and host institutions by simulating a crisis case. The suggested worksheet identifies blind spots of an existing support network and varied roles that period abroad coordinators are expected to undertake. This study further supports the notion of the heavy reliance on period abroad coordinators who have been under a pressure to carry out varied and specialist roles at times of mental health crises of students on their period abroad.

KEYWORDS: mental health, crisis/crises, study/period/year abroad, student, corpus/corpora

INTRODUCTION

In the UK, the Mental Health Foundation reports “the declining state of student mental health in universities and the rapid increase of the total reported number of students who have mental health problems” (2018) and in the context of Higher Education (HE thereafter) sector, Broglia et al. (2018) also confirm the demand for the mental health needs of students is accelerating. Moreover, according to Royal College of Psychiatrists, when looking at the whole student population in the UK, it has to be acknowledged that the numbers of students in HE have expanded rapidly, and they are from more culturally and socially diverse backgrounds. Students are drawn from backgrounds historically low rates of participation in HE. In addition, social changes such as the withdrawal of financial support, higher rates of family breakdown and economic recession are all having an impact on the well-being of students (2011, p.7). These references support anecdotal statements by academic and service staff that they feel they have been attending to more and more students with mental health related concerns in wider and varied manners in UK HE and it is unavoidable to refer to studies by mental health support organisations and in the psychiatric field when discussing student mental health issues as the fields are clearly inter-linked. A question arises: are there any mental health related issues that are distinctively unique to period abroad programmes that have not been investigated yet? And are there any blind spots that have yet been noticed?

The figure of “One-in-four adults (…) experience mental illness during their lifetime” (National Health Service England, ND) or “Approximately 1 in 4 people in the UK will experience a mental health problem each year” (Mind, 2013) have been often cited when discussing the large and growing numbers of the student population with issues related to their mental health in HE. It is noticeable that NHS England and Mind use the terms mental illness and mental health problem as if they are interchangeable. In addition, academic and administrative staff in UK HE who are directly dealing with students may have been using terms such as mental wellbeing or well-being, mental illness, mental health issues, mental health concerns and so forth as if they are synonyms. Have these terms been mainstream worldwide and interchangeable so that when communicating with colleagues at partner institutions abroad they are used under the same understanding?

This study firstly sums up what are considered unique to students’ mental health concerns in the context of the period abroad from available literature. It then examines various terms in literature that refer to mental health related issues by employing online corpora. Although when defined by linguists, corpus may be considered mainly for a quantitative analysis for areas of linguistics, study of language or theories of language (McEnery and Hardie 2011), when it is combined with another area of study, it may further its potential as a means of research. This paper attempts to make a humble contribution by combining the widely available online corpora and references from the field of psychiatry in order to visualise blind spots in the support network for students abroad in crises.

WHAT IS UNIQUE TO A PERIOD ABROAD PROGRAMME IN RELATION TO STUDENTS’ MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES?

During their[2] period abroad, the student may get in touch to request their withdrawal from the programme as early as on the day of arrival at the host institution. Or their host institution may directly contact the coordinator requesting a withdrawal of the student based on their observation that the student’s mental health is deteriorating but it is often without direct communication with or consent from the student.[3] Receiving such communication puts the coordinator in an awkward situation in relation to the General Data Protection Regulation or GDPR. [4]

Based on a small scale of database, Hunley (2010) concluded that “students experiencing more psychological distress and more loneliness did demonstrate lower levels of functioning while studying abroad” (p.389). This reference makes period abroad programmes look high risk for students with mental health concerns. However, according to the Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health[5] (ND), (JCPMH), perceptions of mental health crisis are highly individual. Students with mental health issues often believe or are advised that the current environment is the cause of their problems so a complete change of environment is encouraged for their condition, such as “Since arriving in Prague, both my depression and anxiety have significantly improved” (usatoday 2016[6]). Furthermore, Bathke and Kim (2016) carried out a statistical analysis of the state of student mental health when they are abroad and they reached a positive finding that “studying abroad seemed to improve mental health in some areas” (p.11). Therefore, it is premature to conclude that proceeding to the period abroad programme worsens or risks student’s mental health.

NHS national services of Scotland (ND) lists a wide range of factors that are considered to disrupt stable mental health during travel:

- Separation from family and friends.

- Time zone changes and jet lag/sleep deprivation.

- Disruption of normal routines and travel delays.

- Unfamiliar surroundings and presence of strangers.

- Culture Shock and sense of isolation.

- Language barriers.

- Use of drugs and alcohol.

- Physical ill health during travel.

- Forgetting to take medication regularly.

- Type of travel; some forms have a higher risk e.g. business, family events (wedding/funeral) and volunteer/aid work.

In addition, Bathke and Kim (2016) listed culture shock, relationships, abuse of alcohol and other drugs, grief and coping with loss. Moreover, Oropeza et al. displayed more rigorous entries such as changes in status, expectations about academic performance, alienation, discrimination and miscellaneous stressors in addition to isolation, family related pressures and cultural shock (1991, p.280-1).

Period abroad coordinators know that it is not only during the period abroad but also at pre- and post-period abroad stages they are expected to deal with a variety of issues that are related to students’ mental health needs. In cases of the pre-period abroad stage, internal staff may be in touch with the coordinator regarding a student who is aiming to progress onto their period abroad but is failing to submit assessments for core/compulsory modules, poor attendance, relationships with staff or peers, poor management of finance, insomnia and so on that may carry on during their period abroad. The student’s host institution may also be in touch to enquire about unsettled bills, non-submitted reports or testimonials that had been the agreed conditions of institutional scholarship or students’ social media posts that defamed the host institution at their post-period abroad stage. These varied issues involving partner institutions abroad are expected to be resolved by the period abroad coordinators hence they complicate the overall experience of coordinators who directly deal with the students.

HOW TO CALL IT

From directly cited references, mental wellbeing, mental health problems, mental health crisis, mental health needs or mental illness have been introduced so far in this article. But have they always been used and widely communicated by all concerned and shared the same understanding of such terms when they are used? In this section, by introducing how major health institutions such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), National Health Service (NHS) and American Psychiatric Association (APA), define mental health related terms, the boundaries of such terms are examined and quantify which terms are frequently used.

Mental Wellbeing, Mental Health Problems, Mental Health Crises, Mental Illness or something else?

In its action plan (2013) the WHO describes mental health as “an integral part of health and well-being” (p.7) and that mental disorders “denote a range of mental and behavioural disorders that fall within the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth revision (ICD-10)” (p.6). Or they define mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (WHO 2014). Mental disorders are described as “generally characterized by some combination of abnormal thoughts, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others. Examples are schizophrenia, depression, intellectual disabilities and disorders due to drug abuse” (WHO 2019).

Whilst the APA explains mental illnesses as “health conditions involving changes in emotion, thinking or behavior (or a combination of these)” and mental health as “the foundation for emotions, thinking, communication, learning, resilience and self-esteem. Mental health is also key to relationships, personal and emotional well-being and contributing to community or society” (Parekh 2018).

When we turn our attention back to the UK, “mental health is treated on a par with physical health”(NHS England ND) and “Mental wellbeing means feeling good about yourself and the world around you, and being able to get on with life in the way you want” (NHS 2018). The charity organisation Mind repeatedly uses mental health problems but, in its subcategory, there exist names of disorders such as anxiety disorder, depression, phobias, OCD, panic attack, psychotic disorder, suicidal thoughts and so forth. According to the Mental Health Foundation, anxiety and depression are the most common mental health problems with around 1 in 10 people affected at any one time whilst between one and two in every 100 people experience a severe mental illness, such as bi-polar disorder or schizophrenia, and have periods when they lose touch with reality (2019b).

As seen, it seems boundaries of terms used have been left vague and there are preferred terms that have been used by each institution. In fact, “There is little consistency in how severe mental illness (SMI) is defined in practice, and no operational definitions” (Ruggeri et al. 2000, p.149). In addition, the phrases to refer to mental health related matters also seem to have been left to emerge amongst non-medical experts. In the next section such phenomena are depicted by employing English corpora.

The emergence of terms

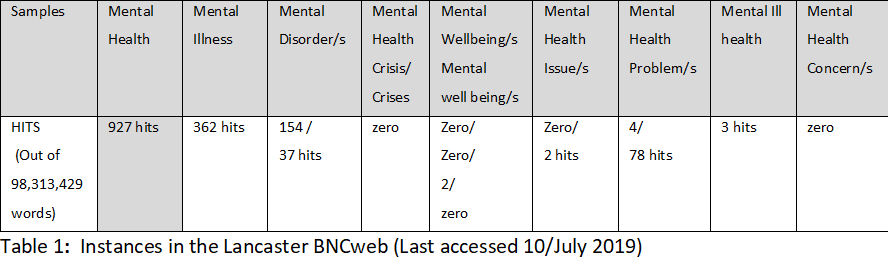

The terms that refer to mental health issues that made appearances in various cited articles, Mental Health, Mental Illness, Mental Disorder/s, Mental Health Crisis/Crises, Mental Wellbeing, Mental Health Issue/s, Mental Health Problem/s, Mental Ill health, Mental Health Concern/s, have been analysed firstly with the Lancaster British National Corpus web. Lancaster BNCweb is based on 98,313,429 words out of 4,048 primarily British English texts between years 1991 and 1994. This particular corpus has been chosen in order to show what terms had been generally used in the UK before statistics of the student mobility by the British Council[7] was made easily accessible that is from 1996 onward (British Council 2020). Table 1 shows that Lancaster BNCweb only picked up three such terms with significance, Mental Health, Mental Illness, Mental Disorder/s, whilst other terms only displayed a few or zero instances. It suggests the other terms were not regularly used in Britain at least during 1991-1994 and possibly before that period.

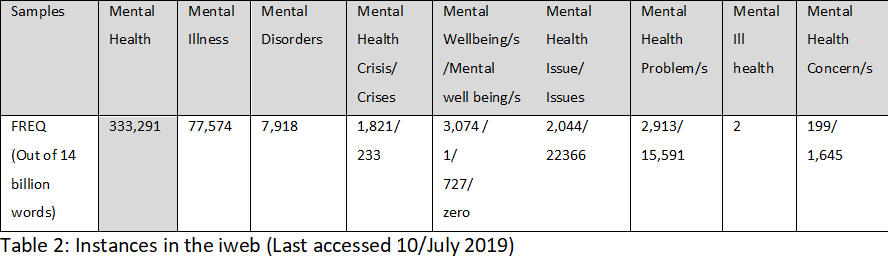

By unlimiting it to British English in early 1990’s and using a much wider database, more terms that are related to mental health emerge. Table 2 displays the results for the same terms, but they have been analysed by the iweb. iweb is based on the database of 14 billion words in 22 million web pages in US, CA, UK, IE, AU and NZ Englishes as of 2017 and they claim to offer unparalleled insight into variation in English (English corpora 2017). Interestingly despite iweb 2017 being a much larger database, mental ill health remains a minority entry with only a couple of instances like it was found in Lancaster BNCweb. It is also noticeable that mental wellbeings is the only sample out of the entries that its plural form has less hits than its singular form based on the analysis.

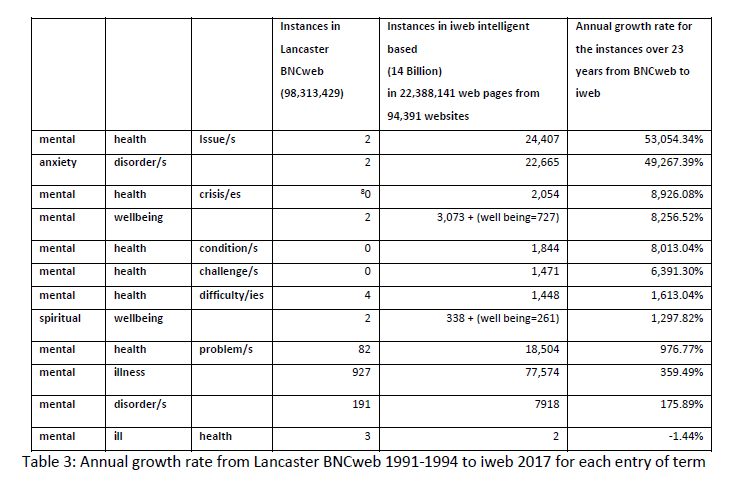

Table 3 has been created to depict the significance of emergence and growing popularities of terms. The growth rates of various mental health related terms have increased more than that of the entire database to confirm that the references to mental health are growing in general. It is noticeable that mental health issue/s and anxiety disorder/s are the fastest growing entries. If it is assumed that Lancaster BNCweb kept on growing into the size of iweb over 23 years from 1914 to 2017, the annual growth of instances over the same period for mental health issue/s and anxiety disorder/s are 53,054.34% and 49,267.39% respectively, whilst the calculated annual growth rate of the entire database size is only 614.79%. Furthermore, despite mental illness scoring the highest in both corpora, its growth rate remains only 359.49% and Mental disorder/s that were commonly used in the UK in 1994 score only 175.89%. Although these medical or blunt unequivocal terms are still growing but not at the rapid growth rate of mental health issue/s, which are overarching terms for more general reference. These results suggest that referring to mental health related concerns have been occurring more and more over the years in English and the favoured terms used are less blunt. When communicating with overseas partner institutions where English is not their dominant language, it is recommended to use more general terms instead of blunt terms and avoid random use of synonyms for the sake of appearance to confuse the recipients.

MENTAL HEALTH CRISIS AND CRISES IN THE CONTEXT OF PERIOD ABROAD

Based on the analysis in the previous chapter, it is noticeable that the third emergent and growing entry, mental health crisis or crises, clearly implies urgency hence immediate attention is required either medically or institutionally unlike other entries listed on the Table 3. What do mental health crisis or crises mean in the context of the period abroad? A student may face crisis or crises, or period abroad coordinators may have to deal with multiple crises. In this section, depicting the expectations of the period abroad coordinator at times of crises in the context of period abroad is attempted.

Clinical Definitions

There are a variety of descriptions similar to dictionary entries such as “A mental health crisis often means that you no longer feel able to cope or be in control of your situation” (NHS 2019). Charity bodies such as the Mental Health Foundation or Mind define a mental health crisis as “an emergency that poses a direct and immediate threat to your physical or emotional wellbeing. There is no one set definition of what a crisis entails; it is highly personal to each individual case and can be escalated by service users, their carers, or family/friends according to what they consider normal/abnormal” (Mental Health Foundation 2019) or “A mental health crisis is when you feel your mental health is at breaking point, and you need urgent help and support. ... Some people feel in crisis as part of ongoing mental health problems, or due to stressful and difficult life experiences such as abuse, bereavement, addiction, money problems or housing problems” (mind 2013b). The common key points here seem to be who are involved and their individual perspectives are expected and respected when dealing with crises. Having these points in mind, JCPMH (ND)’s definition gives a clearer perspective when defining crises:

- Self-definition: defined by the person or carer as a fundamental part of that person owning the experience and their recovery. Identifying potential crises is a skill that can be developed as part of self-management.

- Negotiated or flexible definition: defined as outside the manageable range for the individual, carer or society; to use the crisis service, a decision is reached between the user and the worker.

- Pragmatic, service orientated definition: defined by the service as a personal or social situation that has broken down where mental distress is a significant contributing factor. Crisis is a behavioural change that brings the user to the attention of crisis services and this for example might result from relapse of an existing mental illness. For the team, however, the crisis is the impact of the change on the user and the disruption it causes to their life and social networks.

- Risk-focused definitions: viewed as a relatively sudden situation in which there is an imminent risk of harm to the self or others and judgement is impaired – a psychiatric emergency – the beginning, deterioration or relapse of a mental illness.

- Theoretical definitions: where crisis is viewed as a turning point towards health or illness, a self-limiting period of a few days to six weeks in which environmental stress leads to a state of psychological disequilibrium. Crisis is defined on the basis of the severity, not the type of problem facing the individual, and whether any acknowledged trigger factors for a crisis are present.

Their definitions involve who: individuals and organisations/institutions. The next section explores the possibility of adapting this JCPMH’s definition to the context of a period abroad programme to form a base of situational crisis analysis in order to visualise who are taking what kind of roles at times of student crises abroad and identify blind spots if any.

Who takes care of the crisis?

When the JSPMH definition is viewed in the context of a period abroad programme, it seems safe to presume that the interchangeable terms such as the person, the user, the self or the individual, all directly refer to the student. On the other hand, when attempting to assign responsibilities of the following roles, it suddenly becomes unclear who they could be, how much responsibility that they are expected to carry, when and in which situation at times of student crises abroad:

the carer

the crisis service

the worker

the team

social network

others

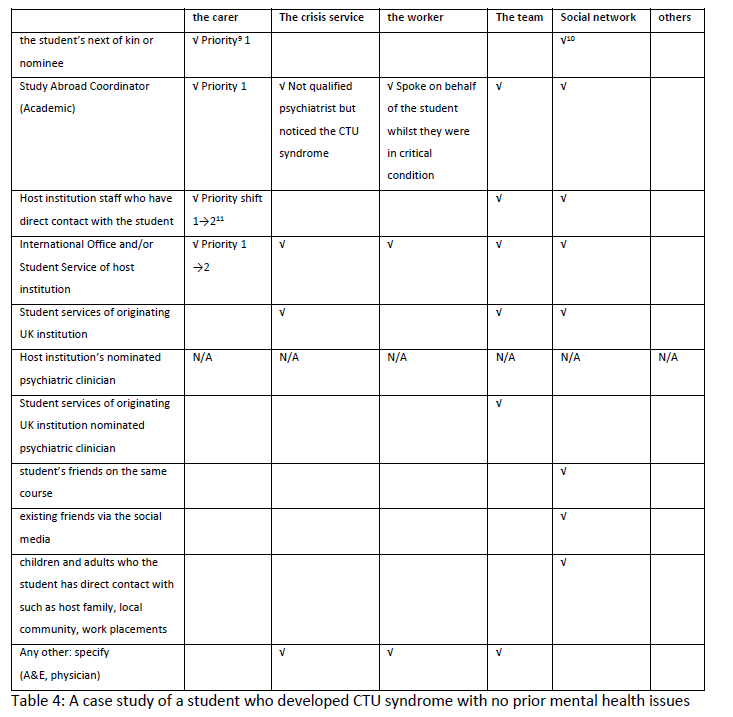

In order to analyse how these identified roles by the JSPMH can be distributed to all concerned who may be involved with the student with mental health issues in the context of a period abroad programme, a worksheet has been prepared. Table 4 is the created sheet for an attempt to examine a case of a student who had no pre-existing mental health issues prior to their period abroad. Because of an accident that they were involved in, they were carried into The Accident and Emergency (A&E) department at hospital and were placed in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The coordinator arrived at the hospital with the student’s next of kin from the UK. The coordinator firstly met with the representative from the host institution and visited the student at the ward. The ICU syndrome, temporary but serious psychiatric symptoms, were observed that the coordinator coincidentally possessed a good knowledge of, therefore a meeting with the physician in charge was requested on the day and it was negotiated that the student to be moved to less harsh environment.

Discussion

Despite the next of kin being present, due to the emergency as well as cultural and language barriers it was the study abroad coordinator who acted for the best interest of the student. The worksheet also depicted the status of the host institution as the carer shifted from priority 1 to 2 as soon as the coordinator arrived. Furthermore, despite the coordinator not being a qualified medical expert or a social worker, the responsibilities that are carried out by the coordinator involved such roles amongst others because such positions were unoccupied and nobody else could fill them on behalf of the student when outside the UK. The coordinator became the key person on behalf of the user in English and Japanese to begin with, later between the user and the hospital/physician in charge and the host institution. Most importantly what the worksheet highlighted is this heavy reliance on the period abroad coordinator outside their trained capacities when dealing with crises abroad.

This worksheet and the method of filling it in are both at very early stages of development and are in need of improvement with further research with various case studies, but it has successfully identified blind spots and ambiguities of the division of responsibilities or roles in this particular case of crisis that previously were hard to visualise. It also has shown the potential that there may be other roles that the period abroad coordinator may have to fill in at times of crises at different situation, location and season abroad.

CONCLUSION

This study investigated terms that refer to mental health related concerns in various literatures using corpora. It confirmed that usages of many mental health related terms have grown significantly larger than the growth rate of the database. Mental illness remains the most used term over two decades but mental health issue/s have been identified as the emerging and fast-growing overarching term when referring to mental health related matters. Previously well used terms in UK, namely mental disorder/s, are found not to have grown much. The results suggest that while over the years users of the English language refer to mental health related concerns more and more, at the same time they come to favour more indirect and less harsh terms. This may be explained due to the culture of softening and chiselling the edges of expression off, in this case students’ mental health, as well as the expectation of the use of synonyms to avoid repetition when writing formally in English. It would be ideal if mental health experts put together guidelines that define the boundaries of each term but as terms emerge and develop where the needs are, that may be an unrealistic expectation. Therefore, when communicating with overseas institutions, staff from institutions where English being their operational language may want to choose terms generally referring to the condition of students instead of using unequivocal terms.

The third classified emerging entry from this investigation, mental health crisis/crises, although their growth rate is not as significant as that of mental health issue/s, this term stands out from the rest of the samples with their urgent implications. They were further explored in the context of the period abroad programme with the creation of a worksheet that is based on the JCPMH’s clinical definitions. The worksheet depicted blind spots in the support network that is formed by the student’s home and the host institution at a time of crisis. Multiple roles to support the student during the mental health crisis have been identified in this simulation and many of them are expected to be taken up by the period abroad coordinator despite some being specialist fields in the UK and the coordinator not necessarily having specific training for these. Although the worksheet itself and the methods of completing the form are still at their very early development stage and in need of further improvements, it has demonstrated its potential for an effective situational analysis or simulation of support networks prior to placing students with mental health issues abroad to identify blind spots in currently available support and take appropriate action in this regard. The worksheet may also be shared when discussing the placement of students between the home and host institutions to be better prepared for support networks.

The study at the same time has depicted the vulnerability, complication and high expectations of period abroad coordinators at times of students’ mental health crises abroad. The managers of coordinators need to be made aware of such demands and arrange training and access to specialist support for the staff.

[1] A period of studying abroad differ course to course: not all students spend an entire year abroad and it may involve work placement. Hence in this article a period abroad is used throughout thereafter.

[2] Gender free pronouns are going to be employed throughout this article.

[3] For example, in Japan, university students are often regarded in need of guardian. On-site medical centre at the host institution or approved physician submit medical note of the student to the institution first before the student gets to see it and it is without a consent of the student. Such medical notes are sent to the coordinator at the home institution.

[4] GDPR was enforceable from 25th May 2018 in UK.

[5] Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health is co-chaired by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of General Practitioners.

[6] https://eu.usatoday.com/story/college/2016/04/06/voices-studying-abroad-is-helping-me-cope-with-mental-illness/37415699/ This story originally appeared on the USA TODAY College blog, a news source produced for college students by student journalists. The blog closed in September of 2017. Published 10:00 AM EDT Apr 6, 2016

[7] The data held by the British Council dates back as far as 1978.

[8] When growth rate is calculated for 0 instances in this column, 1 is used.

[9] Priority: numbered if the responsibility is shared by more than one agent.

[10] √: indicates some involvement.

[11] Several staff at the host institution were taking the priority position until the arrival of the period abroad coordinator from the student’s home institution.

Address for correspondence: tamano@uclan.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Bathke, A. and Kim, R. 2016. Keep Calm and go abroad: the effect of learning abroad on student mental health. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 27, pp.1-16.

British Council. 2020. Student mobility. [Online]. Available from: https://www.britishcouncil.org/education/ihe/knowledge-centre/student-mobility

Broglia, E., Millings, A. and Barkham, M. 2018. Challenges to addressing student mental health in embedded counselling services: a survey of UK higher and further education institutions. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 46(4), pp.441-455.

Department of Health. 2014. The relationship between wellbeing and health: a compendium of factsheets: wellbeing across the lifecourse. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/295474/The_relationship_between_wellbeing_and_health.pdf

English Corpora. 2017. iWeb: the intelligent web-based corpus. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.english-corpora.org/iweb/

Hunley, H.A. 2010. Students’ functioning while studying abroad: the impact of psychological distress and loneliness. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 34(4), pp.386-392.

Joint commissioning panel for mental health (JCPMH). n.d. What is a crisis?. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.jcpmh.info/commissioning-tools/cases-for-change/crisis/what-is-a-crisis/

Lancaster University. Lancaster BNCweb. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: http://bncweb.lancs.ac.uk/cgi-binbncXML/BNCquery.pl?theQuery=search&urlTest=yes

Lindeman, B. ed. 2016. Addressing mental health issues affecting education abroad participants. NAFSA Association of International Educators. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: http://eap.ucop.edu/Documents/Health/Best%20Practices%20Mental%20Health.pdf

McCabe, L. 2005. Mental health and study abroad: responding to the concern. International Educator. Washington. 14(6), pp.52-57.

McEnery, T. and Hardie, A. 2011. What is corpus linguistics? In: Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory and Practice (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics, pp. 1-24). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mental Health Foundation. 2018. The declining state of student mental health in universities and what can be done. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/blog/declining-state-student-mental-health-universities-and-what-can-be-done.

Mental Health Foundation. 2019. Crisis care. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/c/crisis-care

Mental Health Foundation. 2019b. What are mental health problems?. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/your-mental-health/about-mental-health/what-are-mental-health-problems

Mind. 2013. How common are Mental Health Problems?. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/statistics-and-facts-about-mental-health/how-common-are-mental-health-problems/#.XRy_ao8kodU

Mind. 2013b. Crisis services and planning for a crisis. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/guides-to-support-and-services/crisis-services/#.XR4j248kodU

NHS England Transformation & Corporate Operations Business Planning Team. 2016. Our 2016/17 Business Plan. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2016/03/business-plan-2016/

NHS England. 2016. Implementing the five year forward view for mental health-implementation plan - 4. Adult mental health: common mental health problems. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/taskforce/imp/

NHS England. n.d. About mental health. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/about/

NHS National Services of Scotland. n.d. Mental health and travel. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/advice/general-travel-health-advice/mental-health-and-travel#risk

NHS. 2018. Learn for mental wellbeing. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/learn-for-mental-wellbeing/

NHS. 2019. Dealing with a mental health crisis or emergency. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/using-the-nhs/nhs-services/mental-health-services/dealing-with-a-mental-health-crisis-or-emergency/

Oropeza, B.A.C., Fitzgibbon, M. and Baron, A.J.R. 1991. Managing mental health crises of foreign college student. Journal of Counselling and Development. 69(3), pp.280-284.

Parekh, R. 2018. What is mental illness? [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness

Ratliff, R. E. 2015. The relationship between spiritual well being and college adjustment for freshmen at a Southeastern University. Growth: The Journal of the Association for Christians in Student Development. 5(5), pp.28-36.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2011. Mental health of students in higher education: College Report CR166. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr166.pdf?sfvrsn=d5fa2c24_2

Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2019. Problems and disorders. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/problems-disorders.

Ruggeri, M., Leese, M., Thornicroft, G. and Bisoffi, G. 2000. Definition and prevalence of severe and persistent mental illness. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 177(2), pp.149-155.

WHO. 1993. ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/

WHO. 2013. Mental health action plan 2013-2020. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/action_plan/en/

WHO. 2014. Mental health: a state of well-being. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/

WHO. 2019. Mental disorders. [Online]. [Accessed 11 September 2019]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/en/