Are our students ready for a shift in how grammar is taught and the format in which is presented for practice?

1.INTRODUCTION: CHANGING PERSPECTIVES IN GRAMMAR TEACHING AND LEARNING

According to Nunan (1986, p.3), if we want to put students at the centre of learning, then we need to take into account their needs and attitudes. In this sense, the aim of this study was precisely to analyse students’ attitudes and perceptions towards two different ways of explaining and presenting the same grammar content in order to introduce modifications and adapt the teaching materials to the students’ needs and preferences.

As far as methods and approaches usually used for teaching Spanish is concerned, although the communicative approaches (advocated and promoted in the European Framework of References for the Languages CEFR) have been accepted and adopted by applied linguists and practitioners with enthusiasm (Nunan, 1986, p.2), there seems to be a mismatch between what teachers and learners perceive as useful in the classroom (Nunan, 1986, p.4). Hence, the need to identify and monitor students’ perceptions about what should be happening in the classroom and how they think this should be happening. On the other hand, according to Llopis-García, Real-Espinosa and Ruiz-Campillo (2012) the teaching of grammar, and more specifically of Spanish grammar, has been focusing for many years on the form rather than on the meaning or the communicative purpose underlying a specific tense or mode, and there is a need to shift from the traditional approach to a more communicative one. The activities designed according to a traditional conception of grammar teaching have mainly consisted of filling the gaps exercises in which sentences were deprived of any context and the only cue to get the right answer was the analysis of the linguistic form or syntactic structure. On the other hand, a teaching of grammar based on a cognitive approach whereby grammar forms are dependent on the subjective ways in which the speaker perceives and organises reality (Slobin, 1996, p.76) has been consistently advocated and implemented in recent years in the field of second language acquisition and more specifically in the teaching of Spanish grammar (Llopis-García, Real-Espinosa and Ruiz-Campillo, 2012). According to this approach, not only the context but also the speaker’s intention or purpose will determine which tense or mode is more suitable to meet those needs. In this sense, the activities designed according to this conception will have to immerse the learner in a specific reality—with more information provided—which will be close to any actual situation with which the learner will be confronted in the future when using the target language, which will, in turn, prove to be more effective than traditional ways of presenting the grammar based on repetition and memorization (Molina-Vidal, 2016). However, and according to Ruiz-Campillo (2007, p.1) there is a lack of a pedagogical grammar based on the concept of cognitive grammar, and most Spanish textbooks still present the grammar from a behaviourist point of view (2007, p.5). These observations lead us to assume that advanced students who have been learning Spanish for several years have been mainly taught through tasks and activities based on the traditional model described above. Thus how can tutors know whether students are willing to reorganise the—in most cases—already settled ways of applying Spanish grammar rules, which have been consolidated over the years? On the other hand, do they prefer a more traditional paper-based way of presenting grammar practice or will they enjoy the alleged benefits of using digital tools and games? (Gee, 2003; Godwin-Jones, 2014; Garland, 2015; Figueroa-Flores, 2015). These are the two main questions that gave rise to the intervention proposed in this paper, which is to compare learners’ perceptions of two activities dealing with the same grammar content but based on two different conceptions of how grammar should be taught and presented for practice.

2.TRADITIONAL, HARD COPY AND NON-INTERACTIVE VS. COGNITIVE, ONLINE, GAME

As mentioned in the previous section, a cognitive approach to teaching grammar regards tenses and modes as elements that interact with reality, as a means for the speaker of making sense and conveying meaning and intention. Thus, the importance of context and the need to immerse in the actual situation of communication that the cognitive approach prioritises, aligns with the idea of dialogues, situations or stories, as opposed to single sentences which lack the necessary pragmatic information required to make grammatical decisions. Therefore, an activity based on a cognitive approach should consist of at least a dialogue or a story in which enough context is provided, so that the learner can make a decision not based on mere memorization or application of a rule. In this sense, the online tool Twine, which allows the designer to create a story that unfolds according to the choices that the reader makes between two options that are given, seemed appropriate to design an activity according to a cognitive approach (Molina-Vidal, 2016, p.10). Such a tool provides context and it is interactive—it works like a game in which, depending on the reader’s decisions between two tenses or modes (two different past tenses or indicative/subjunctive modes), the story will follow one path or another and will progress towards reaching a goal or come to an end. This interaction also implied that the player or user is getting immediate feedback about the decisions that are made.

On the other hand, in the format in which the activity was presented, the concept of gamification (Werbach and Hunter, 2012) and its potentials benefits for learning were taken into account. According to Godwin-Jones (2014, p.11) “serious games” are designed specifically for educational use and therefore can be tailored to meet learning and curricular needs, and some of the affordances of using online games in language learning include:

- It is highly motivating for students who are not interested in formal education. This idea has also been supported by Figueroa-Flores (2015).

- It provides extensive practice of the target language.

- It is a safe environment where multiple participants playing at the same time and interacting feel comfortable and create an ‘affinity space’ (Gee, 2003).

The consideration of both these aspects—cognitive approach and gamification—and the choice of Twine for designing one of the activities proposed in this paper has already been elaborated and supported in Molina-Vidal (2016).

Conversely, according to a behaviourist or traditional approach, there is no need to give a context in order to decide which tense or mode is the right one, provided that the activity includes a sentence with a specific structure, which is linked to a grammar rule that the learner will apply. According to this, another activity was designed consisting in ten sentences with a verb in brackets, which had to be written in the appropriate mode—either indicative or subjunctive. In most of the sentences there were some cues that helped the learner to decide which one was the correct mode. However, there were some sentences in which both indicative and subjunctive were possible and there was no information or enough context to assist in making that decision. In those instances, in which both options were possible, the student had to justify his/her decision by providing a plausible context in which either the indicative or the subjunctive (depending on their choice) would work. This activity was presented in a piece of paper, and contrary to the online activity, it was not designed as a game nor was it interactive—there was no goal to be achieved depending on the learner’s decisions. Also, no answers were given to the students, so they could not receive immediate feedback or check autonomously whether they were right or wrong but the answers were discussed with the whole class. In summary, the characteristics of the two activities proposed and compared in this paper are outlined in table 1:

| Activity 1 (Based on a cognitive conception of grammar teaching) |

Activity 2 (Based on a behaviourist conception of grammar teaching) |

| · A story | · Sentences without a context or only few contextual information |

| · Online access | · On paper |

| · A game – interactive | · Not a game – not interactive |

| · Answers provided immediately | · Answers are not provided for self-correction |

Table 1 Characteristics of Activity 1 and 2

In addition to this, in the design of this study the potential benefits and downsides of the specific features in both activities—and their impact in the learner’s reactions and perceptions of teaching and learning—were also taken into consideration. For example, while activity 1 could be more beneficial because the learner has to make decisions in situations, which are similar to real life and this will thus promote a practical use of the grammar content in real communicative situations, this could also constitute a downside. If students usually resort to their memorization of the rules and the purely linguistic cues to make grammatical decisions, they will not know how to use the context to define the speaker’s communicative intention and hence to make the right choices.

On the other hand and as far as the context is concerned, although the activity presented using a digital tool is a game, and this could be motivating for students, there were also some potential benefits associated with the paper format in which the other activity was presented. According to Longcamp et al. (2005) handwriting as opposed to typewriting contributes to the recognition of letters. Also, a study conducted by Thomas and Dieter in 1987 (in Luttels, 2015, p.9) showed that handwriting facilitated the memorization of French words, and in general, the acquisition of new vocabulary in a second language (Pichette et al., 2011). The hypothesis that handwriting might facilitate memorization is based on the Involvement Load Theory, which argues that the involvement load of a task, influences the effectiveness of language acquisition (Hulstijn and Laufer, 2001). Accordingly, if handwriting takes more time than typing (Mangel and Velay, 2010), this means that the task will involve more load and thus, will promote more memorization. A brief summary of the advantages and disadvantages of both activities is included in table 2:

|

Activity 1 (Based on a cognitive conception of grammar teaching) |

Activity 2 (Based on a behaviourist conception of grammar teaching) |

||

|

Strengths |

Weaknesses | Strengths |

Weaknesses |

|

+ Linked to real life situations and use. + Increased motivation and engagement through the game. + Immediate feedback and answers. |

- Students are not familiar with the approach or the format in which the activity is presented. The activity takes more time and effort to complete. | + It is a type of activity that students already know. It takes less time to complete.

+ It is the type of activity usually used in exams and assessments.

+ Handwriting promotes memorization. |

- The lack of context makes it less related to real life situations or use of language.

- It is less motivating and less engaging because is not a game. - Answers and explanations of different possible contexts are not provided immediately but discussed with the whole class. |

Table 2: Potential Strengths and Weaknesses of both activities

3.CONTEXT OF THE INTERVENTION AND ACTIVITIES PROPOSED

Table 3 displays the profile of the group of students who participated in this intervention. Students were asked to complete two different types of activities but both of them aimed at practicing the same grammar content, namely, the use of the modes indicative and subjunctive in relative clauses in Spanish. Students already knew from previous years this structure and the grammar rule, which determines the use of one mode or the other. The two activities were as follows:

| Group Characteristics | |

| Type of learner | University undergraduates studying Spanish as foreign language. |

| Number of participants | 100 |

| Level of competence in the target language |

B2+/C1 according to the CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference). All of them had spent at least one semester in a Spanish-speaking country. |

| Language Learning Approaches used in the past for learning the language | Since all undergraduates had started learning Spanish before entering University, it is assumed that they were exposed to a variety of different learning methodologies and approaches to language learning, including the traditional-behaviourist one. |

Table 3: Group Characteristics

Activity 1: Online activity/game using the digital tool Twine and based on a cognitive approach to the teaching and learning of grammar.

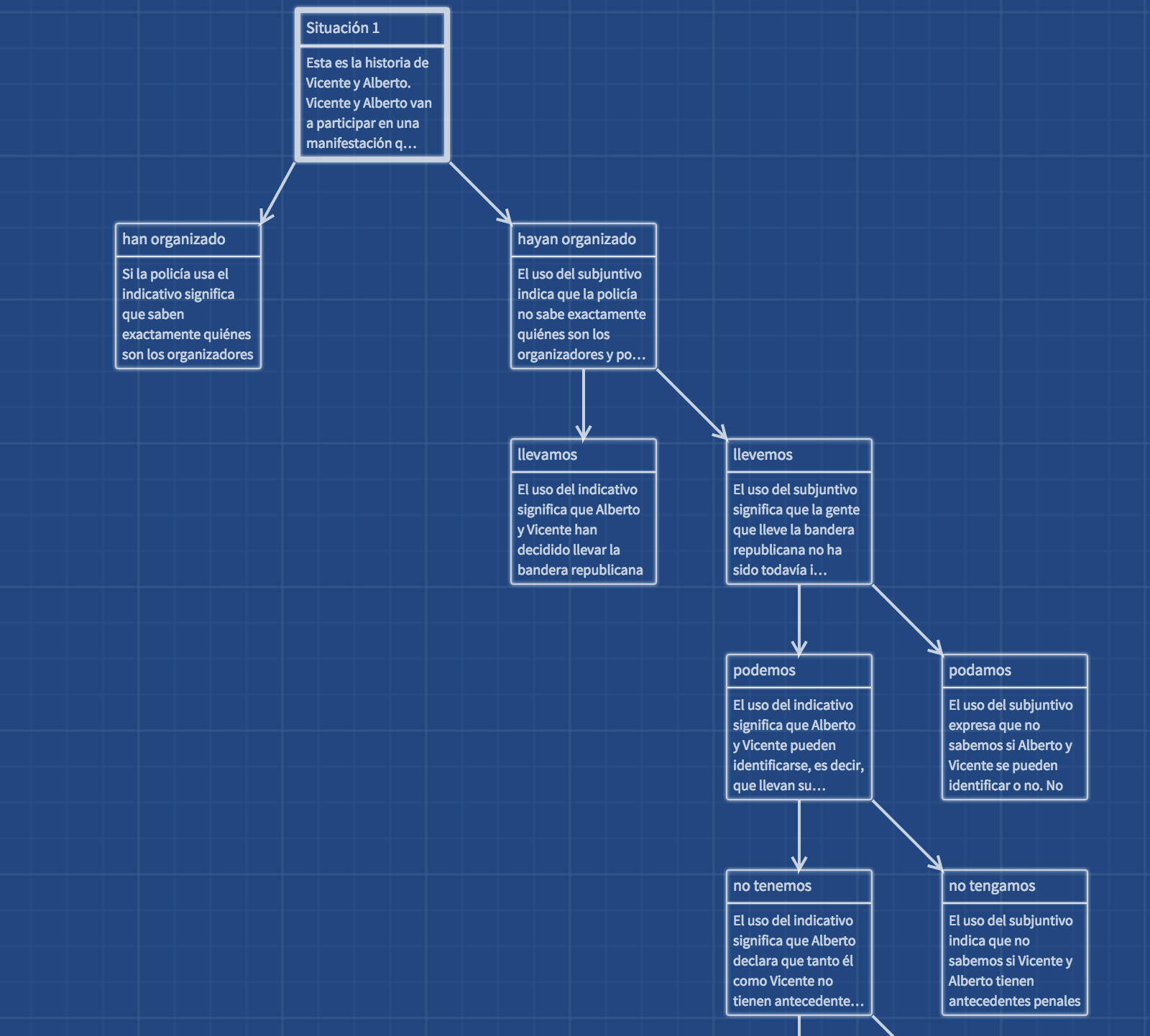

Students could access through the virtual learning environment Minerva from the University of Leeds to an online activity designed using the digital tool Twine. The activity was presented as a story called The Protest, in which the player has to make the right decisions (choosing indicative or subjunctive modes in relative clauses) so that the main characters in the story avoid to be identified and arrested by the police. If the player/learner makes the right choices the story progresses and the player moves to the next screen, which includes and explanation of why that was the right choice, and a new situation with two new options to choose from. If the player chooses the wrong option, he/she will be led to a screen explaining why that was a wrong choice and why the goal of saving the main characters from the police was not achieved and hence the story has ended. Screen shot 1 shows the edit mode of the digital tool Twine, in which we can see how some boxes (screens) lead to other boxes through arrows and how other boxes or situations come to a dead end, meaning, that the option was wrong and the story is finished.

Screen Shot 1: How Twine works (edit mode)

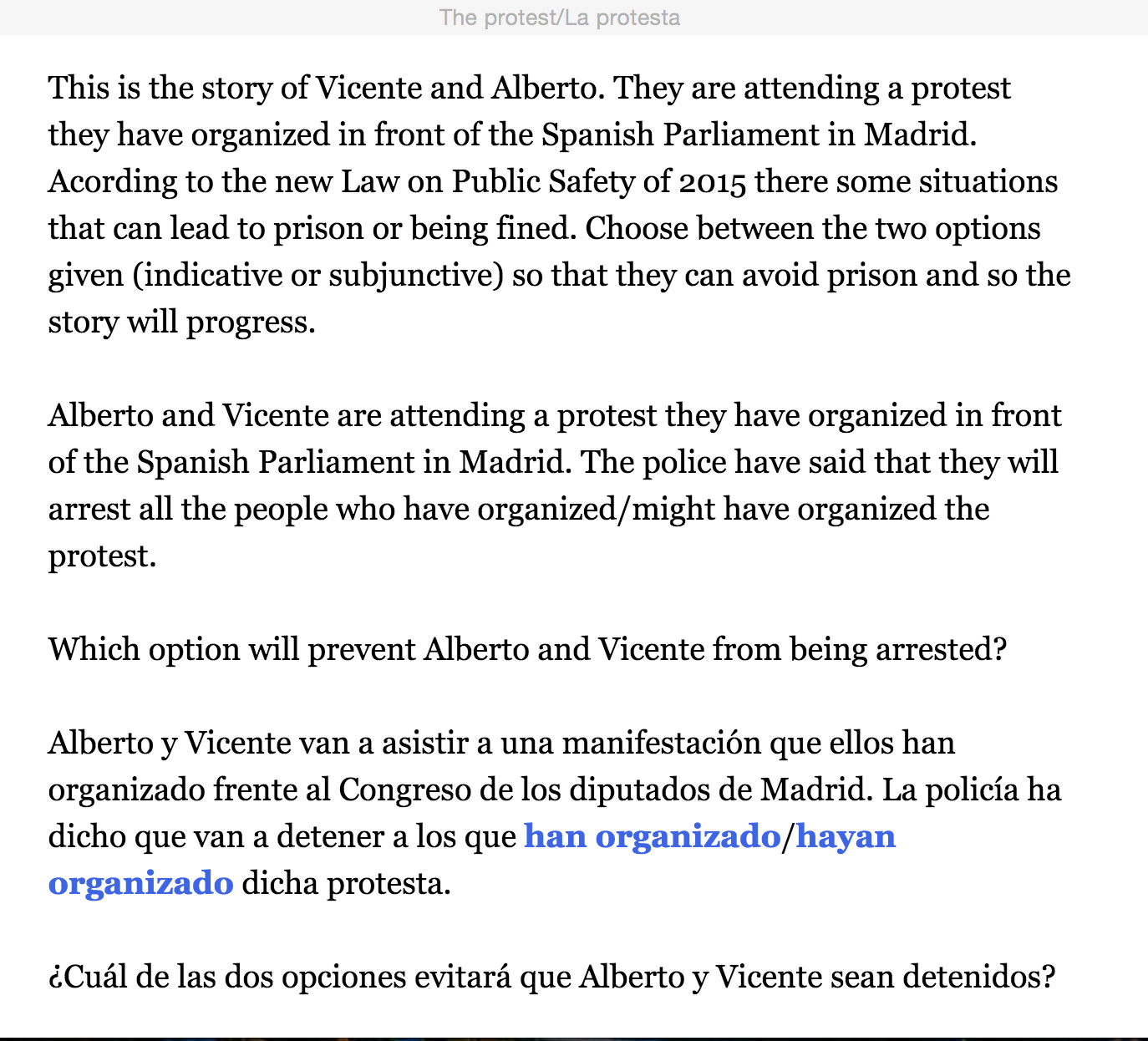

Screen shot 2 shows the first situation the player sees when using the digital tool and the two options highlighted as a link to the next screen.

Screen Shot 2: Situation 1: Presenting the story

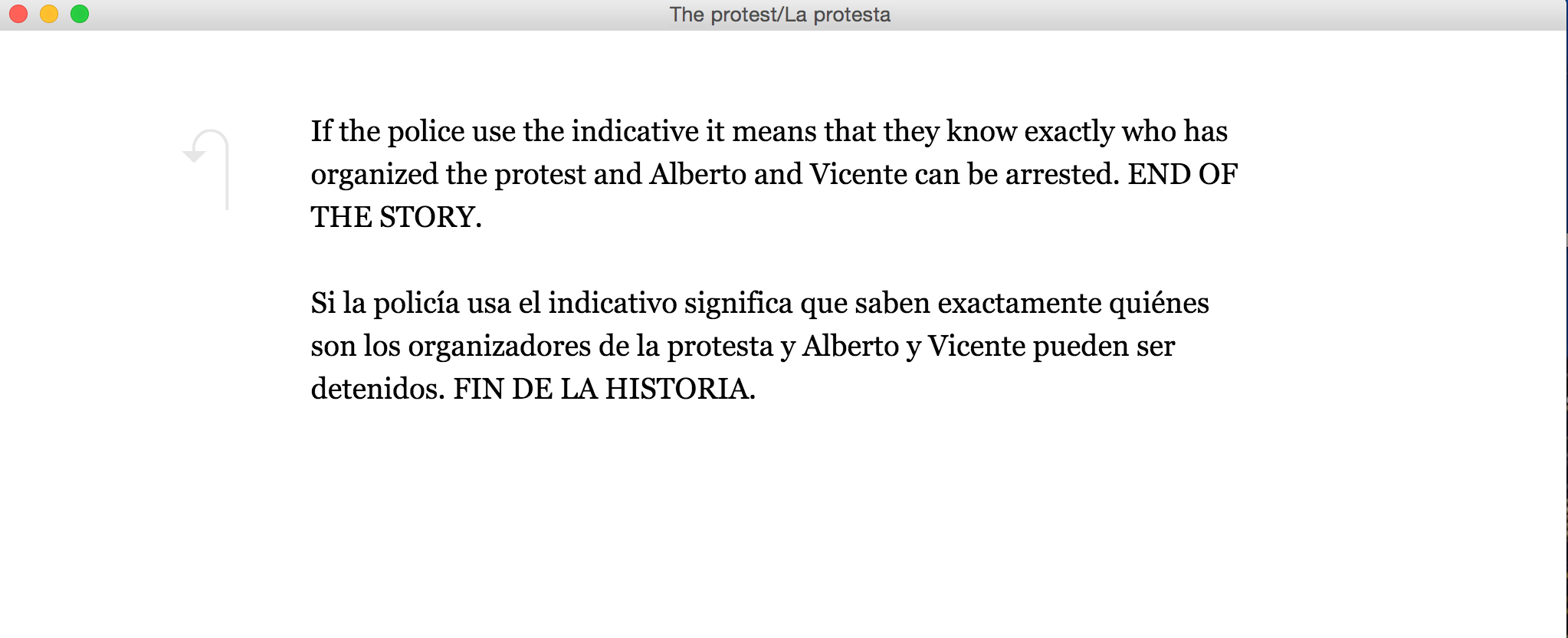

Screen shot 3 shows the screen that will appear if the player/learner chose indicative ‘han organizado’ in the previous screen, which was the wrong option.

Screen Shot 3: Screen that appears after wrong option is chosen

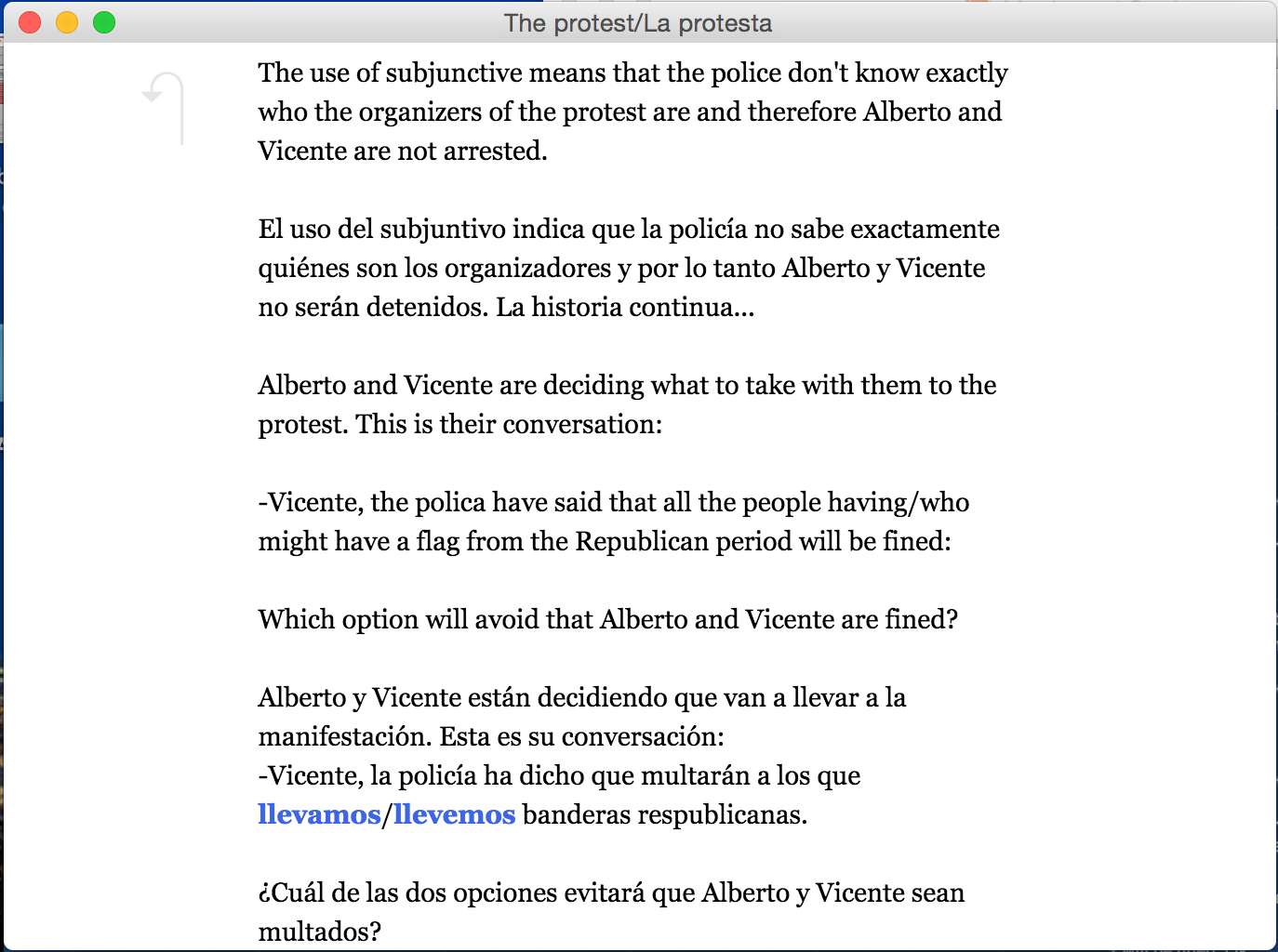

Screen shot 4 shows the screen that will appear if the player/learner chose subjunctive ‘hayan organizado’ in the previous screen, which was the right option.

Screen Shot 4: Screen that appears after right option is chosen

The activity was conducted in class but students had to complete it individually and autonomously. There was no need to check with the whole group the answers because the digital tool provides with explanations for all the choices, hence immediate feedback.

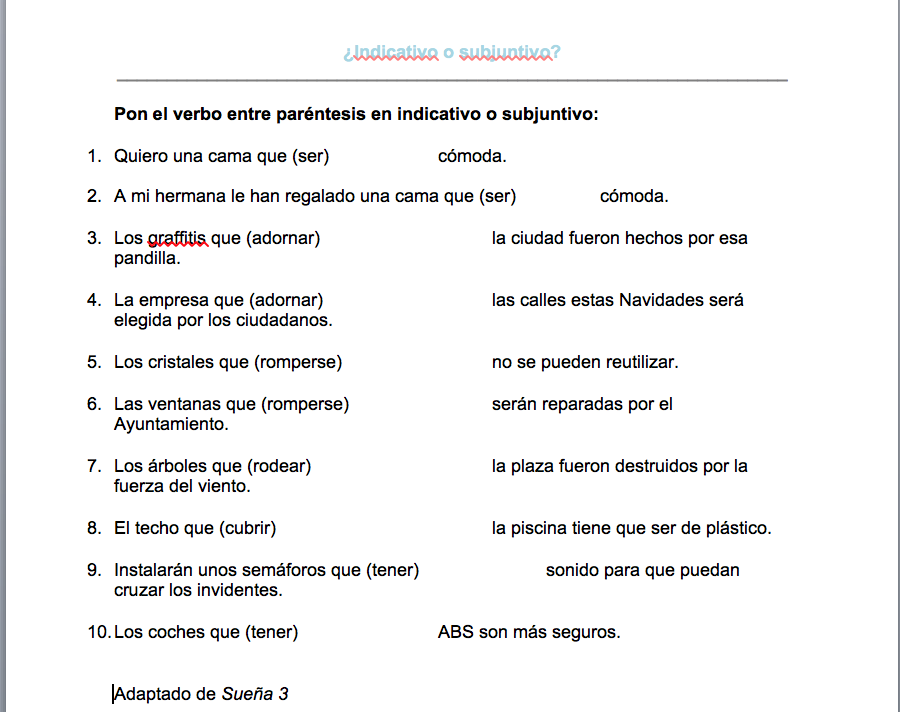

Activity 2: A sheet of paper with 10 sentences (some of them adapted from the Spanish textbook Sueña 3) to fill in the gaps and designed according to a traditional and behaviourist conception of language teaching. Screen Shot 5 shows this activity.

Screen Shot 5 – Activity 2: Sentences to Fill in with Indicative or Subjunctive

Activity 2 was conducted in class but students had to complete it individually and autonomously. After completion all the answers were given and discussed with the whole group and in the case that both modes indicative and subjunctive were possible in a sentence, students were asked to provide an appropriate context in which each one of the forms will work.

Once students had finished both activities they were asked to fill out a brief questionnaire. The questionnaire had been designed using the digital tool Survey Monkey to collect learners’ perceptions and reactions with regards to the two activities presented. The questionnaire included four questions –three multiple-choice questions and one open question– and were the following:

1.Which one of the two activities did you find more difficult?

- Online digital tool

- Activity on paper

- Both of them are equally difficult

2.In which one of the two activities did you have more right answers?

- Online digital tool

- Activity on paper

- In both of them

3.Which one of the two activities ‘online digital tool’ or ‘activity on paper’ did you find more effective to learn the difference between indicative and subjunctive? Why?

4.Which type of activity would you like to do in the future to practice your Spanish?

- Online digital tool

- Activity on paper

- Both of them

- None of them

A hundred responses were collected.

4. RESULTS

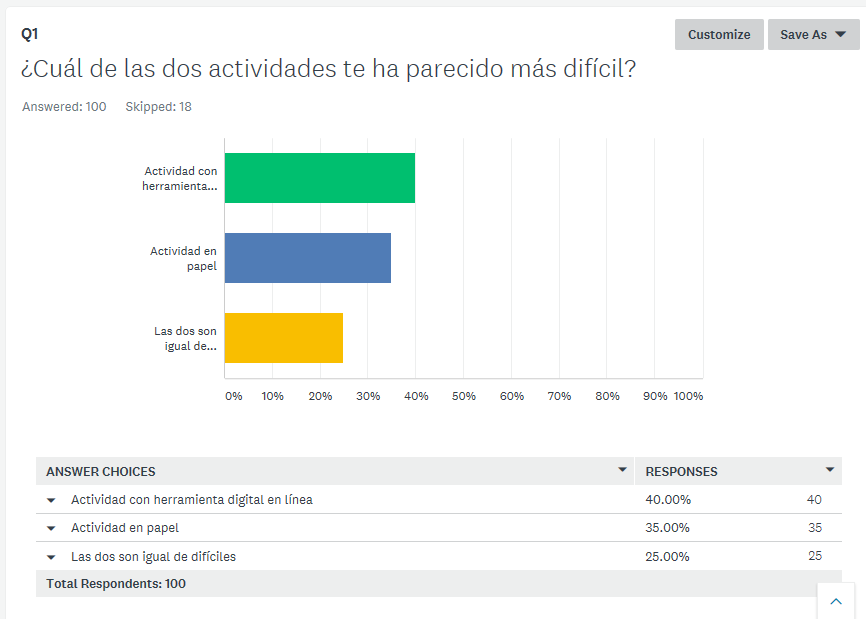

Figure 1 shows the answers to question 1: Which one of the two activities did you find more difficult?

Figure 1: Q.1: Which one of the two activities did you find more difficult?

According to the responses, a majority of 40% of undergraduates found the activity using the digital tool Twine more difficult than the activity on paper. 35% of the students found the activity on paper more difficult than the online activity, and, finally, 25% of the students found both of them equally challenging. Figure 2 shows the results for question 2: In which one of the two activities did you have more right answers?

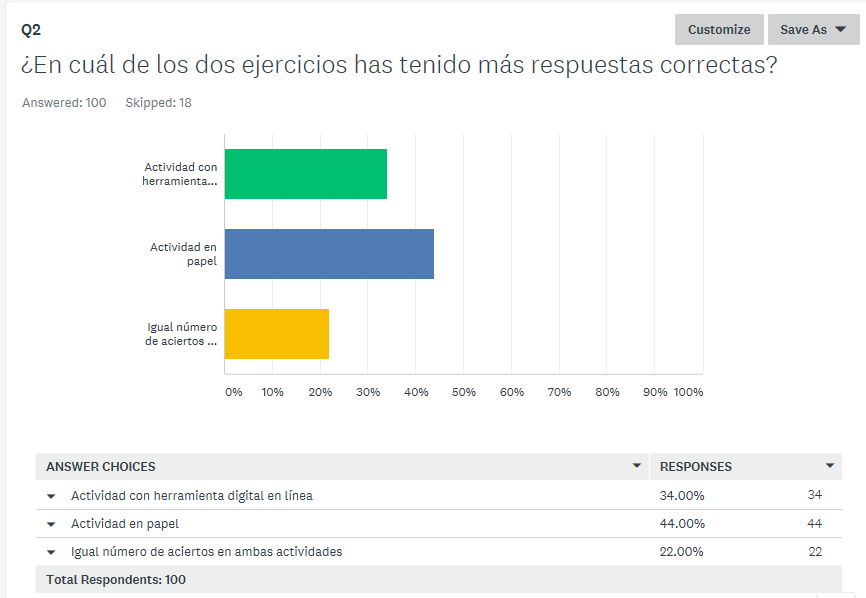

Figure 2: Q.2: In which one of the two activities did you have more right answers?

Most of the students (44%) had more right answers in the activity on paper than in the online activity (34%). A percentage of 22% of the participants had equal right or wrong answers in both activities.

Question 3 included two questions, firstly, which one of the two activities ‘online digital tool’ or ‘activity on paper’ did you find more effective to learn the difference between indicative and subjunctive? And, secondly, Why? The results to this question are twofold: On the one hand, how effective students found each one of the activities and on the other hand the reasons underpinning their choices. Table 4 shows the answers to the first question, namely, which one of the activities proposed was more effective for the practice of indicative and subjunctive in relative clauses for which four main categories of responses were identified:

| Table 4: Which one of the two activities ‘online digital tool’ or ‘activity on paper’ did you find more effective to learn the difference between indicative and subjunctive? | |

| More effective activity | Percentage % |

| Online activity | 49% |

| Activity on paper | 32% |

| Both | 17% |

| N/A or not question-related answer | 2% |

As far as the second question of question 3 is concerned, that is, why students found one activity more efficient than the other in order to practice the difference between indicative and subjunctive, the answers will be presented in relation to each one of the four categories shown in table 4:

-"The online activity was more effective": All responses in which the online activity was chosen as the most effective included one of the following elements:

- More context was helpful to make decisions (32 responses included this aspect).

- The situations presented are more related to real-life situations (7 responses).

- Immediate feedback and solutions (5 responses).

- Good and clear explanations after each screen (19 responses).

- Interactivity and the possibility of doing the activity again even if the answer was wrong (4 responses).

- It is a different and entertaining way of learning (5 responses).

Screen shots 6 to 13 (see appendix) show some of the answers supporting the choice for online activity as the most effective according to the factors mentioned before. A translation into English of those comments is provided below:

‘I liked the online activity more because there was a story, which made it easier to understand individual situations’. (Participant 8).

‘The online activity. Although none of my answers were correct, I think that knowing the context gives you more opportunity to choose the right option’. (Participant 45).

‘The first activity because there is an explanation of the context, in which we have to choose between two options. This is more similar to a real-life situation.’ (Participant 1).

‘Online because it gives me “feedback” that helps me understand why I was right/wrong. In paper, it is possible to get the right answer without knowing the reason why’. (Participant 56).

‘Online because the correct answers are explained in a way that it is easy to understand’. (Participant 10).

‘Online is more interactive. There are consequences from our choices’. (Participant 51).

‘Online you can try again and also you get immediate feedback. Also, there is no risk of losing the piece of paper’. (Participant 61).

‘The online activity was more entertaining and with good explanations’. (Participant 71).

-The activity on paper was more effective: The answers of the participants who preferred the activity on paper are related to one of the following aspects:

- Easy to read and to memorize (2 responses).

- More examples and short sentences provided which make the activity look easy (6 responses).

- The possibility of making notes on the paper and accessibility to the activity for further practice and study (12 responses).

- Answers need to be discussed or explained by the tutor because no immediate feedback is provided (2 responses).

- There are no options and the conjugated form is not provided, so it is necessary to think carefully about the right response (6 responses).

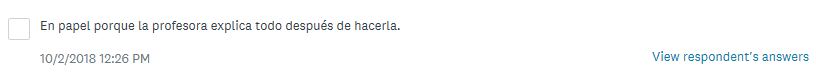

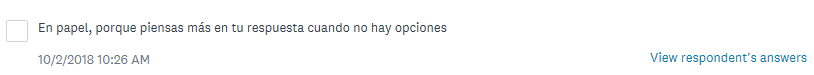

Screen Shots 14 to 22 (see appendixes) include the comments that justify why students chose the activity on paper as the most effective according to the factors mentioned before. A translation into English of those comments is provided below:

‘On paper, I find it difficult to pay attention to the activity on my phone. The text is small and external notifications may distract’ (Participant 2).

‘On paper, because I remember better the information after the activity’ (Participant 11)

‘On paper the sentences seemed easier’ (Participant 57).

‘On paper because I can write the correct answer next to the question’ (Participant 33).

‘On paper because it is possible to keep it in your folder and it is easier to find for further study. It is possible to forget if there are activities on Minerva. (Sorry for the lack of accents it is difficult in my ipad if it does not appear automatically haha). (Participant 39).

‘The activity on paper because there are times when the difference is very subtle and it has to be discussed and, sometimes, defend the ‘incorrect’ answers’. (Participant 31).

‘On paper because the teacher explains everything after completing the activity’. (Participant 38).

‘On paper because you have to think more about the answer when the options are not provided in the activity’. (Participant 54).

‘On paper because we need to conjugate the verb’. (Participant 98).

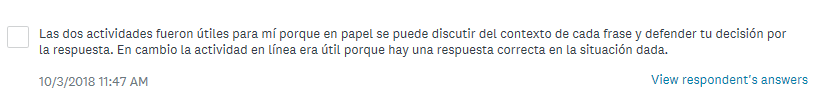

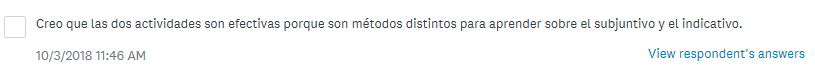

-Both activities were considered equally effective: 17% of the participants regarded both activities as equally effective for a combination of reasons related to the aspects mentioned before and referred to the online activity and the activity on paper. Screen shots 23 to 26 (see appendixes) present some of the ideas supporting the effectiveness of both activities. A translation into English of those comments is provided below:

‘Both activities were useful for me because on paper you can discuss the context in each sentence and defend your decision in that sentence. On the contrary, the online activity was useful because there is a right answer for each given situation’. (Participant 12).

‘I think that both activities are effective because they show different methods to learn subjunctive and indicative’. (Participant 17).

‘For me, they are the same. I like the online activity because it is more fun and after each exercise the answer is explained. But the activity on paper present the grammar in a more formal context and it is more difficult’. (Participant 75).

‘The first (online) helped me because it links the use of subjunctive to situations, while the activity on paper was easier, maybe because there are short sentences and it is easier to find the information that helps you to make a decision. Also, I can underline my thoughts on paper’. (Participant 77).

Finally, there were two answers, which were not considered for analysis because either the participant refused to give an answer and reply with N/A to the question, or the answer was not dealing with the effectiveness of the activities but with the difficulty of both tasks, which was the content of question 1.

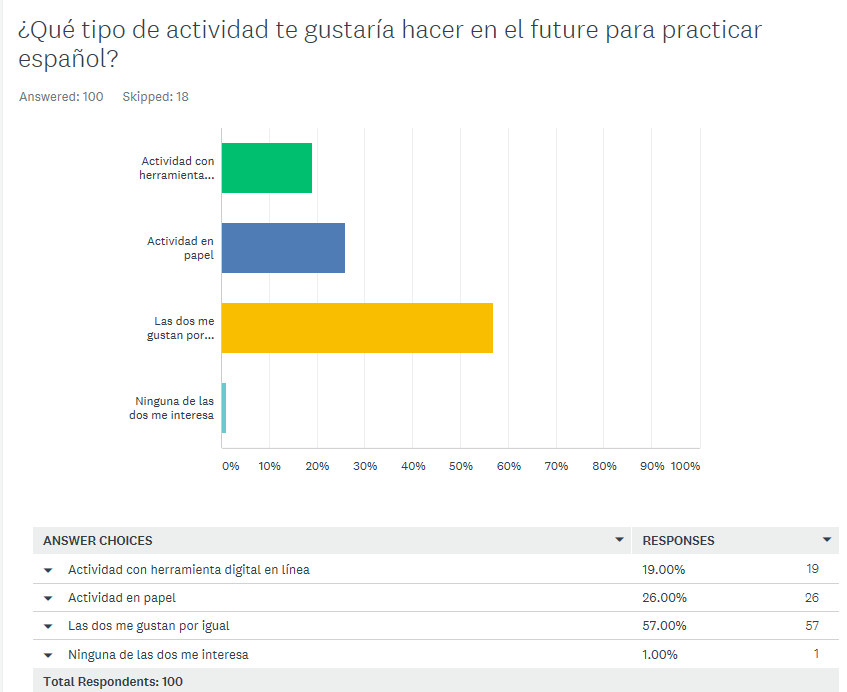

The final question included in the survey was aimed at finding out students’ preferences for future activities and practice of Spanish grammar. Figure 3 shows the results linked to question 4: Which type of activity would you like to do in the future to practice your Spanish?

Figure 3: Q.4: Which type of activity would you like to do in the future to practice your Spanish?

The figure shows that a majority of the students (57%) preferred to have both types of activities to practice their Spanish. 26% of them showed more interest in the activity on paper than on the online activity (19%) and 1% of the participants expressed no interested in neither of them.

5. DISCUSSION

According to results from question 1, a majority (40%) of participants found the online activity more difficult than the activity on paper. There might be some reasons supporting this idea:

- Students are not familiar with the type of format that is being used for presenting or practising the grammar. Thus, in addition to thinking about the grammar rule to be applied they need to understand how the activity works and the implications of their decisions.

- In the online activity only one of the options was correct and the story is designed in a way that if the student does not have a clear understanding of the uses of indicative and subjunctive in relative clauses, it is not possible to make a reasoned decision. In this sense, some of the students might have found out that, in fact, they thought they knew the rule in theory but they don’t when it comes to applying it to real situations and contexts. Also, in the online activity only one of the options was correct, while in the activity on paper there was more flexibility and some sentences could accept both indicative and subjunctive and it was up to the student to provide a context in which his/her decision would work.

- As pointed out by some participants in question 3, the short sentences of the activity on paper as opposed to the long text/story of the online activity made the activity on paper look easier and more accessible than the online one.

On the other hand 35% of the students found the activity on paper more difficult. This could be due to any of the following reasons:

- The lack of context in the sentences made it more difficult to choose between indicative and subjunctive. Students might have felt that they were filling the gaps with one option or the other but they didn’t really know why.

- As mentioned by one of the participants in question 3, the activity on paper demanded from the student to conjugate the verb in the appropriate form, while in the online activity the form in indicative or subjunctive was already provided. This may have posed an extra effort on completing the activity on paper.

- The fact that they were not getting immediate feedback or getting the option of repeating the activity—as in the online activity—might have put more pressure on making the right decision.

Finally 22% of the responses show an equal degree of difficulty in both activities. This might be explained by a combination of any of the reasons mentioned before in favour of one activity or the other. For example, the student might find the online activity difficult because there is only one correct answer while in the activity on paper in some sentences both indicative and subjunctive could work, but, conversely, on the activity on paper there was no context and, thus, the student has to think about both the form and the appropriate context that would suit that verb mode.

As far as the results of question 2 is concerned, there seems to be a correlation between these and those of question 1, whereby a majority of participants 44% had more correct answers in the activity on paper. This aligns with the majority of responses stating that the online activity was more difficult (40%) in question 1, meaning, that if they found the online activity more difficult that is why their choices were incorrect. On the other hand, since some of the sentences in the activity on paper accepted both indicative and subjunctive as correct answers, this will explained why most of the students had more correct answers in the activity on paper.

Regarding question 3 in the survey, the analysis of the qualitative data allows to identify some trends in students’ perceptions of both activities and how these relate to either the type of approach or the format. A majority of 49% of the participants thought that the online activity was more effective in terms of learning and practising the grammar, and this has been linked to some of the following factors mentioned in the previous section:

- More context was helpful to make decisions (this comment is related to the type of approach to teaching the grammar).

- The situations presented are more related to real-life situations (this is related to the type of approach to teaching the grammar).

- Immediate feedback and solutions (this is related to online game format)

- Good and clear explanations after each screen (this is related to the online game format).

- Interactivity and the possibility of doing the activity again even if the answer was wrong (this is related to the online game format).

- It is a different and entertaining way of learning (this is related to the online game format).

From these data it can be drawn that students prefer to have as much information as possible or context, in activities to practice Spanish grammar. Also, participants appreciated the similarity of the examples included in the activity with real-life situations. Immediate feedback and clarification of the responses is also highly valued in an activity, as well as the possibility of repeating the exercise. Finally, the originality of the activity and the gaming component seem to be regarded as positive in an activity but only a few answers highlighted this aspect.

On the other hand the benefits and effectiveness of completing the activity according to a traditional approach of grammar teaching and on paper according to 32% of the responses were linked to the following aspects:

- Easy to read and to memorize (this is related to the format).

- More examples and short sentences provided, which make the activity look easy (this is related to a traditional approach to grammar teaching).

- The possibility of making notes on the paper and accessibility to the activity for further practice and study (this is related to the format).

- Answers need to be discussed or explained by the tutor because no immediate feedback is provided (this is related to the format).

- There are no options and the conjugated form is not provided, so it is necessary to think carefully about the right response (this is related to the format).

Some of the participants found it difficult to read and focus when the activity was presented online. Also, they felt it was easier and more convenient to keep a physical copy of the activity for further review and study than the non-tangible virtual one. The fact that they could write by hand on the piece of paper seemed beneficial for some of the participants as well, and some even highlighted that the activity on paper was better for memorization purposes. This information is relevant to understand how the physicality or tangible nature of some working processes and tools is still necessary for some students to retain and learn more efficiently as opposed to the virtual and non-tangible online tools. Also, this aligns with what has been pointed out at the beginning of this paper regarding the benefits of handwriting for the memorization of words. Thus it could be drawn from some of these observations that the contact through touch with the learning tools establishes a beneficial connection for some students, which promotes learning.

On the other hand, the provision of more context in the online activity seemed to be not so beneficial to other students who pointed out that short sentences made it easier to complete the exercise. Additionally, the need to conjugate the verb in the activity on paper was regarded as more effective because it forced them to think about tenses and forms.

Finally, it is worth noting that also for some of them immediate feedback was not as useful or effective as the need to discuss and reason the answers with the tutor and the whole class after completion of the activity. This piece of information is particularly useful for the analysis of students’ preferences because it shows the importance of dialogue and the co-construction of knowledge for some learners as part of the learning process. This idea is in tune with Ausubel’s conception of learning, according to which learning is a process in which pre-existing ideas in the cognitive structure assimilate new concepts through interaction (1985:75). In this same sense Vygotsky (1978:33) proposed the concept of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), an area in which previous ideas and new information interact thus facilitating the development of new skills. Accordingly, for some of the participants in the survey this kind of interaction is necessary and useful for them to learn and it is more effective than immediate feedback or explanations that are read but not discussed.

Finally 17% of the participants thought that both activities were equally effective for different reasons and this was supported by a combination of the factors mentioned above and which favoured either the online activity or the activity on paper. This response is linked, in turn, with question 4 in which students are asked about their preferred activities to practice Spanish in the future. The aim of this question was to identify students’ preferences at the beginning of the academic year in order to design materials that respond to their needs and introduce them over semester 1 and 2. The results of question 4, however, are not so aligned with responses in question 3 because, although a majority of the participants (49%) agreed in question 3 in that the online activity was more effective—leading us to conclude that this would be the activity most preferred in the future—in question 4 the majority of the students (57%) stated that they would like to have both activities for future and further practice of Spanish grammar. In this sense, it seems that learners acknowledge the different aspects that both activities are covering in the learning process and, although in general they see more effectiveness and practicality in the online activity, they are also reluctant to miss the aspects of the more traditional way of presenting content through the activity on paper.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Regarding the main question of this study, namely, whether our students are willing to practice Spanish grammar according to a cognitive approach, the analysis of results seems to indicate that although they found the online activity more difficult (40%), they also considered that it was more effective (49%), and they are willing to incorporate it as part of their learning and practising experience along with more traditional activities (57%).

In general, students appreciate the provision of more context and the connection with real-life situations of the online activity as well as the immediate feedback and the possibility of multiple attempts.

As far as the second question of this study is concerned, namely students’ attitudes towards the format in which the activities were presented, the answers are not conclusive as to whether they prefer the online format or the paper. Only a few participants explicitly mentioned the gaming component as a positive aspect and one student described the activity on paper as more formal that the online activity, meaning that learners may still regard games as informal and not suitable form of studying grammar. This may be due to the traditional view of grammar to which students have been usually exposed over the years. According to this traditional view, grammar is regarded as a hard, rule-based, strict discipline, which responds to the straightforward application of rules and based on memorisation rather than a more flexible approach in which contextual circumstances and the speaker’s point of view play a role.

Conversely, participants highlighted the possibility of writing on a piece of paper—which promotes visualization and memorization of information—the need to discuss with the whole class the different options in the activity on paper and tutor’s explanations as beneficial for their learning process. Thus, undergraduates appreciate the use of both types of activities in the teaching and learning process, which means that they acknowledge both the affordances and the limitations that each of them encompass. This, in turn, is related to the limitations of the study and the need for further exploration of this topic. Such limitations include, for example, the lack of information regarding autonomous learning and the setting where the activities have been performed. In this sense, another question could have been added to the survey, in which students had to reflect on the suitability of the activity for autonomous learning or learning with the whole class, and also the most suitable place to conduct this type of learning –at home/autonomous learning vs. classroom/learning with classmates and the tutor. In doing so, a more clear distinction and correlation between the nature of the activity (traditional, on paper/online, game), its suitability for a specific setting (classroom/home), type of learning (autonomous/tutor-guided in a group) or stage in the process of learning (early stages of applying the rule or late stages of practice in which the rule is already known and activities are aimed at consolidating knowledge) could have been drawn. Despite this, this study also offers some affordances and useful information, which may include:

- Getting first-hand information about students’ conceptions of the teaching and learning process.

- Getting first-hand information about student’s preferences for practising Spanish grammar.

- Getting confirmation of the need to cover different learning styles in the classroom by offering students different types of activities.

- Assessing the extent to which students are willing to accept new approaches and materials to learn and/or practice the grammar.

- Getting information to design activities dealing with the same content but with different purposes: autonomous learning, application or consolidation of a rule, practice at home or in the classroom.

- Getting confirmation that students do appreciate the interactivity and discussion in the classroom with the tutor and the rest of their peers as part of the learning process, thus counteracting the fear that digital technologies would replace face-to- face tuition and the concept of technological determinism (Oliver, 2011).

To summarize, this study shows the benefits of designing activities according to different formats and various learning approaches to respond to different students’ needs. Additionally, it also reflects the importance of exposing learners to new and innovative ways of learning and practising language content, so that they have a wide range of resources available to manage and monitor their own learning process. The results of the survey also show that in general undergraduates are willing to integrate new ways of practising grammatical content and they embrace the use of digital tools, while still holding on to the traditional and familiar ways of learning even if they think that the new ones are more effective. This way of thinking seems to be prompted, among other factors, by traditional visions of grammar as a strict, formal and difficult aspect of language while the online game may be regarded as informal, and also by the degree of familiarity of the student with traditional activities to which they are more accustomed. Anyhow, both the affordances and limitations of using digital technologies in learning (as pointed out by many students in the survey) seem to be aligned with the concept of blended-learning, meaning, that different types of activities may coexist but online games might be more appropriate for further practice and autonomous learning at home while other formats would be more suitable for discussion in class.

Finally, the whole study emphasizes the need for tutors to engage in a constructive discussion and negotiation with our students regarding learning approaches and materials. If one of the aims of teaching languages is not only to teach how to communicate but also what means to be a learner and how to become a more autonomous learner (CEFR, 2001, p.141) then we must invite students to critically reflect on their own learning experiences and adapt our materials to meet their needs.

Address for correspondence: I.molinavidal@leeds.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Achard, M. 2008. Teaching Construal: Cognitive Pedagogical Grammar. In: Robinson, P. and Ellis, N.C. eds. Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. New York: Routledge, pp.432-455.

Alonso, R. et al. 2005. Gramática básica del estudiante de español. 2nd ed. Barcelona: Difusión.

Álvarez Martínez, M.A. et al. 2001. Sueña 3. Madrid: Anaya.

Ausubel, D. 1985. Learning as constructing meaning. In: Entwistle, N. ed. New directions in educational psychology 1. Learning and teaching. Basingstoke: Taylor and Francis Ltd.

Boyle, T. and Ravenscroft, A. 2012. Context and deep learning design. Computers & Education. 59(4), pp.1224-1233. [Online]. [Accessed 13 May 2015]. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257171432_Context_and_deep_learning_design

Conole, G. 2008. New Schemas for Mapping Pedagogies and Technologies. Ariadne 56 [no pagination]. [Online]. [Accessed 15 April 2015]. Available from: http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue56/conole/

Ellis, N. and Cadierno, T. 2009. Constructing a second language: introduction to the special section. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, Special section: Constructing a second language. 7, pp.111-139. [Online]. [Accessed 28 November 2015]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233514528_Constructing_a_Second_Language_Introduction_to_the_Special_Section

Evans, V. 2014. The language myth. Why language is not an instinct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fauconnier, G. 1997. Mappings in thought and language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Figueroa-Flores, J.F. 2015. Using gamification to enhance second language learning. Digital Education Review. 27, pp.32-54. [Online]. [Accessed 20 October 2016]. Available from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1065005.pdf

Garland, C.M. 2015. Gamification and implications for Second Language Education: A Meta- Analysis. Culminating Projects in English. 40. [Online]. [Accessed 17 May 2016]. Available from: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/40/

Gee, J.P. 2003. What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. ACM Computers in Entertainment. 1(1), pp.1-4. [Online]. [Accessed 14 January 2015]. Available from: https://historysfuture.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/gee-what-video-games-3pp.pdf

Godwin-Jones, R. 2014. Games in Language Learning: Opportunities and

Challenges. Language Learning & Technology. 18(2), pp.9–19. [Online]. [Accessed 4 March 2016]. Available from: http://llt.msu.edu/issues/june2014/emerging.pdf

Hulstijn, J. H. and Laufer, B. 2001. Some empirical evidence for the involvement load hypothesis in vocabulary acquisition. Language learning. 51(3), pp.539-558. [Online]. [Accessed 26 June 2016]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/0023-8333.00164

Krashen, S.D. 1982. Principles and practice in second language acquisition. London: Phoenix ELT.

Longcamp, M., Zerbato-Poudou, M.T. and Velay, J.L. 2005. The influence of writing practice on letter recognition in preschool children: A comparison between handwriting and typing. Acta psychologica. 119(1), pp.67-79. [Online]. [Accessed 20 March 2019]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001691804001167?via%3Dihub

Luttels, K. 2015. The haptic effect of writing on vocabulary learning: a comparison between handwriting and typewriting. MA thesis, Tilburg University. [Online]. [Accessed 20 March 2019]. Available from: http://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=136359

LLopis-García, R. 2010. Gramática cognitiva para la enseñanza de ELE. PhD thesis. Monografías N.14. Ministerio de Educación. Secretaría de estado de educación y formación profesional. [Online]. [Accessed 7 September 2017]. Available from: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/PdfServlet?pdf=VP15263.pdf&area=E

LLopis-García, R., Real-Espinosa, J.M. and Ruiz-Campillo, J.P. 2012 Qué gramática enseñar, qué gramática aprender. Madrid: Edinumen.

Mangen, A. and Velay, J. L. 2010. Digitizing literacy: reflections on the haptics of writing. In: Zadeh, M.H. ed. Advances in haptics, London: IntechOpen, pp.385-401. [Online]. [Accessed 20 March 2019]. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/advances-in-haptics/digitizing-literacy-reflections-on-the-haptics-of-writing

Molina-Vidal, I. 2016. Thinking the grammar: teaching a cognitive grammar using digital tools in a blended-learning context. The Language Scholar. (0), pp.19-30. [Online]. [Accessed 18 October 2018]. Available from: http://languagescholar.leeds.ac.uk

Nunan, D. 1986. Communicative language teaching: the learner’s view. [Online]. [Accessed 20 March 2019]. Available from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED273092.pdf

Oliver, M. 2011. Technological determinism in educational technology research: some alternative ways of thinking about the relationship between learning and technology. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 27(5), pp.373-384. [Online]. [Accessed 11 February 2016]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00406.x

Pichette, F., De Serres, L. and Lafontaine, M. 2011. Sentence reading and writing for second language vocabulary acquisition. Applied Linguistics. 33(1), pp.66-82. [Online]. [Accessed 21 March 2019]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274178861_Sentence_Reading_and_Writing_for_Second_Language_Vocabulary_Acquisition

Robinson, P. and Ellis, N. 2008. Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. New York: Routledge.

Ruiz-Campillo, J. P. 2007. El concepto de no-declaración como valor del subjuntivo. Protocolo de instrucción operativa del contraste modal en español. In: Pastor, C. ed. Actas del programa de formación para profesorado de ELE 2006-2007. Múnich: Instituto Cervantes de Múnich, pp. 89-146. [Online]. [Accessed 9 November 2014]. Available from: https://cvc.cervantes.es/ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/publicaciones_centros/PDF/munich_2005-2006/04_ruiz.pdf

Ruiz-Campillo, J. P. 2007. Gramática cognitiva y ELE. marcoELE. Revista de didáctica ELE. (5). [Online]. [Accessed 5 June 2015]. Available from: https://marcoele.com/gramatica-cognitiva-y-ele/

Tyler, A. 2012. Cognitive linguistics and second language learning. New York: Routledge.

Twinery.org. Twine open-source tool for telling interactive, non-linear stories. [Online]. [Accessed 16 March 2016]. Available from: https://twinery.org

Vygotsky, L. 1978. Interaction between learning and development. Mind and society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp.29-36. [Online]. [Accessed 29 November 2015]. Available from: http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~siegler/vygotsky78.pdf

Warschauer, M. 1997. Computer-mediated collaborative learning: theory and practice. Modern Language Journal. 81(4), pp. 470-481. [Online]. [Accessed 24 October 2014]. Available from:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1997.tb05514.x/epdf

Werbach, K. and Hunter, D. 2012. For the win: how game thinking can revolutionize your

business. Philadelphia, PA: Wharton Digital Press.

APPENDICES

Screen Shots 6-13: The online activity was more effective

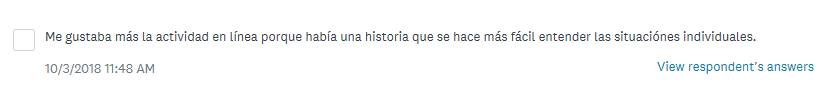

Screen Shot 6: Context

‘I liked the online activity more because there was a story, which made it easier to understand individual situations’. (Participant 8)

Screen Shot 7: Context

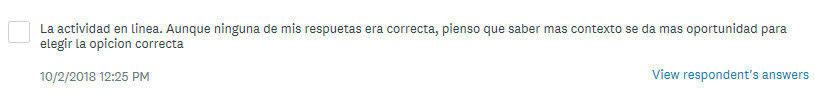

‘The online activity. Although none of my answers were correct, I think that knowing the context gives you more opportunity to choose the right option’. (Participant 45).

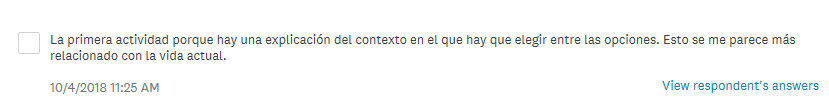

Screen Shot 8: Real-life related situations

‘The first activity because there is an explanation of the context, in which we have to choose between two options. This is more similar to a real-life situation.’ (Participant 1).

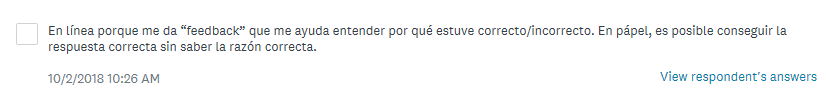

Screen Shot 9: Immediate feedback

‘Online because it gives me “feedback” that helps me understand why I was right/wrong. In paper, it is possible to get the right answer without knowing the reason why’. (Participant 56).

Screen Shot 10: Clear explanations

‘Online because the correct answers are explained in a way that it is easy to understand’. (Participant 10).

Screen Shot 11: Interactivity

‘Online is more interactive. There are consequences from our choices’. (Participant 51).

Screen Shot 12: The possibility of trying again

‘Online you can try again and also you get immediate feedback. Also, there is no risk of losing the piece of paper’. (Participant 61).

Screen Shot 13: Entertaining

‘The online activity was more entertaining and with good explanations’. (Participant 71).

Screen Shots 14-22: The activity on paper was more effective

Screen Shot 14: Easy to read

‘On paper, I find it difficult to pay attention to the activity on my phone. The text is small and external notifications may distract’ (Participant 2).

Screen Shot 15: Easy to remember

‘On paper, because I remember better the information after the activity’ (Participant 11).

Screen Shot 16: Sentences seem easier

‘On paper the sentences seemed easier’ (Participant 57).

Screen Shot 17: The possibility of writing on the paper

‘On paper because I can write the correct answer next to the question’ (Participant 33).

Screen Shot 18: Easier to keep for further learning

‘On paper because it is possible to keep it in your folder and it is easier to find for further study. It is possible to forget if there are activities on Minerva. (Sorry for the lack of accents it is difficult in my ipad if it does not appear automatically haha). (Participant 39).

Screen Shot 19: The need to discuss the answers

‘The activity on paper because there are times when the difference is very subtle and it has to be discussed and, sometimes, defend the ‘incorrect’ answers’. (Participant 31).

Screen Shot 20: Answers are explained by the tutor

‘On paper because the teacher explains everything after completing the activity’. (Participant 38).

Screen Shot 21: Thinking more carefully about the answer

‘On paper because you have to think more about the answer when the options are not provided in the activity’. (Participant 54).

Screen Shot 22: The need for conjugating the verb

‘On paper because we need to conjugate the verb’. (Participant 98).

Screen Shots 23-26: Both activities were considered equally effective

Screen Shot 23

‘Both activities were useful for me because on paper you can discuss the context in each sentence and defend your decision in that sentence. On the contrary, the online activity was useful because there is a right answer for each given situation’. (Participant 12).

Screen Shot 24

‘I think that both activities are effective because they show different methods to learn subjunctive and indicative’. (Participant 17).

Screen Shot 25

‘For me, they are the same. I like the online activity because it is more fun and after each exercise the answer is explained. But the activity on paper present the grammar in a more formal context and it is more difficult’. (Participant 75).

Screen Shot 26

‘The first (online) helped me because it links the use of subjunctive to situations, while the activity on paper was easier, maybe because there are short sentences and it is easier to find the information that helps you to make a decision. Also, I can underline my thoughts on paper’. (Participant 77).