Investigating barriers to peer review on foundation courses: how to increase active participation

Catriona Johnson

Centre for Academic Language & Development, University of Bristol

ABSTRACT

Recent pedagogic literature has reframed the role of the student in the feedback process from a passive receiver of comments to an active participant able to generate, decode and use feedback comments to set learning goals and improve future work (Boud and Molloy, 2013; Winstone and Carless, 2021). As well as advocating more dialogic feedback between tutors and students, the literature promotes the use of peer review to create more active feedback opportunities. This exploratory study investigates common barriers to active participation in peer review workshops on foundation courses, with the aim of recommending ways to promote learners’ agentic engagement with the process of giving, receiving and implementing peer feedback (Winstone et al., 2017). Thematic analysis of data from surveys and interviews with 28 students and 6 tutors on an international foundation programme at a UK university indicates that the main barriers relate to cognitive, social, affective, and linguistic factors. Although triangulation of the student and tutor data revealed many shared perceptions of the factors that facilitate and hinder participation in peer review, key differences also emerged: students prioritised the need for accountability whereas tutors emphasised the role of regular reflection. Using the student feedback literacy framework (Carless and Boud, 2018), the findings were analysed further to suggest pedagogical recommendations for overcoming these barriers to incentivise students to take a more active role in the process, at the same time as developing their overall feedback literacy. This more scaffolded approach to peer review includes suggestions for material design and classroom practice and aims to build students’ confidence with engaging in multiple acts of evaluative judgement without the guidance of the teacher (Nicol, Thomson and Breslin, 2014).

KEYWORDS: peer review, student feedback literacy, active participation, proactive recipience

BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Nicol, Thomson and Breslin (2014) define peer review as a reciprocal process whereby students produce feedback reviews on the work of peers in exchange for reviews on their own work. These reviews tend to include feedback on strengths, weaknesses and suggestions for improvement to encourage learners to revise and improve their writing (Yu and Hu, 2017). This reciprocal process relies heavily on student interaction and collaboration in line with social constructivist theories of learning (Hussain, 2012), as students work together with their peers to improve their essay drafts within the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978). Academics agree that for peer review to be effective, students need to be active agents in the process, by questioning and discussing the feedback they give and receive, as well as applying any learning to their future writing (Carless and Boud, 2018; Molloy, Boud and Henderson, 2020; Nicol, 2011). To achieve this agentic engagement, Winstone et al. (2017, p.17) emphasise the importance of developing students’ awareness of the responsibility they have in making feedback effective, a term which they define as “proactive recipience.” Although this term refers to feedback processes in general, recent studies by Banister (2020) and Hoo, Deneen and Boud (2021) have examined how to nurture this sense of responsibility specifically in peer review activities.

However, much of this recent research has focused on how undergraduate and postgraduate students can benefit from developing their ability to give, receive and seek feedback from their peers (Hoo, Deneen and Boud, 2021; Tsui and Ng, 2000; Winstone and Carless, 2021). Associated benefits include being able to evaluate and improve their own work more effectively, develop their own internal perception of ‘quality’, and build confidence with the skill of reviewing, useful for their future academic and professional lives (Nicol, 2011; Nicol, Thomson and Breslin, 2014). To date, very few of these studies have focused on foundation level students, who arguably need more support and scaffolding with this complex academic skill, which is often far removed from their previous feedback experiences. Many international foundation students are used to adopting a passive role in the feedback process where the teacher is considered the ‘teller’ (Carless and Boud, 2018) and where feedback is conceptualised as ‘a gift from the teacher to the learner’ (Askew and Lodge, 2000, p.5). With this in mind, Kostopoulou and O’Dwyer’s (2020) research sought to investigate peer review on foundation and pre-master courses, looking specifically at how the development of reflective and metalinguistic skills could increase active participation. Their findings suggest that foundation students would significantly benefit from developing the skill of reviewing to prepare them more adequately for peer and self-assessment at undergraduate level. Therefore, this exploratory study builds on the previous research by investigating challenges that international students face with peer review on foundation courses. It seeks to answer the following two questions:

- What are the main barriers to active participation in peer review workshops?

- How can active participation in peer review workshops be increased?

As well as the gap in the pedagogic literature, another impetus for the study was an observed lack of participation with peer review activities in the first teaching block of an International Foundation Programme at the University of Bristol. Observations included a lack of preparation for the workshops, a reluctance to share or comment on each other’s written work and minimal interaction between students, even when time was given for post feedback discussion and goal setting. Researchers in this field suggest a range of reasons for these barriers, including the influence of the students’ cultural backgrounds and previous learning experiences. Winstone and Carless (2019) attribute many of these challenges to cultural factors, claiming that students from collectivist cultures may be more naturally inclined to engage in peer support than those from individualistic cultures. Although Banister (2020) agrees that culture can influence student engagement, his research suggests that linguistic and social barriers have a more significant impact, as a lack of social connection between students combined with insufficient language required for the task, often inhibits their participation. In contrast, Winstone and Nash (2019) emphasise cognitive factors, for example, how a lack of appropriate strategies for unpacking and responding to feedback can create a barrier. Therefore, this study seeks to gain a better understanding of the main challenges that international foundation students face when participating in peer review.

In addition to these cultural, linguistic, cognitive and social barriers, the tutor's approach to feedback can also significantly influence student engagement with peer review. Boud and Dawson (2021) acknowledge that the increased emphasis on student feedback literacy has created a need for professional development in terms of tutor feedback literacy. Molloy, Boud and Henderson (2020) agree that tutors often require training in how to actively involve students in the feedback process, particularly with how to structure effective peer review workshops. Indeed, some tutors may avoid peer review altogether, favouring more conventional transmission-focused feedback practices instead (Winstone and Carless, 2021). Therefore, active student participation may also require a cultural shift for some tutors. In the same way, the tutor needs to provide students with systematic training in the classroom to demonstrate the cognitive skills involved in peer review, so that they are encouraged to incorporate peer feedback into their revised essays (Lam, 2010; Min, 2006; Zhu, 1995). Min (2006) suggests two main stages, including in-class modelling and one-on-one discussions with the tutor, whereas Lam (2010) proposes a more scaffolded three-tiered coaching approach with a modelling stage, exploring stage and consciousness-raising stage. These initial modelling and exploration stages can be executed using exemplars or collaboratively written essays to train students to notice the gap between their own writing and other academic texts (Carless et al., 2018).

Another important part of the tutor’s role is to explain the benefits of giving feedback, as students often place more value on receiving comments, not fully appreciating the higher-order thinking skills that are involved in feedback generation, such as applying criteria and critically evaluating strengths and weaknesses (Winstone and Carless, 2019). Many studies have specifically examined the impact of reviewing on the students' engagement and uptake of peer feedback. Cho and MacArthur’s (2011) research with undergraduate students on a laboratory physics course, highlighted the positive effects of the act of reviewing, as students developed a greater understanding of the needs of the reader and the role of the audience in written communication. Their research emphasised some of the key processes involved in reviewing; namely, problem detection, diagnosis and solution generation, which could later be used as self-review tools after students had developed enough confidence through peer review. These cognitive processes activated by generating peer feedback were further investigated by Nicol, Thomson and Breslin (2014) during their study with first year engineering design students at the University of Strathclyde. Once again, their findings confirmed that evaluating the work of peers and giving feedback could increase students’ agentic engagement with feedback processes in general.

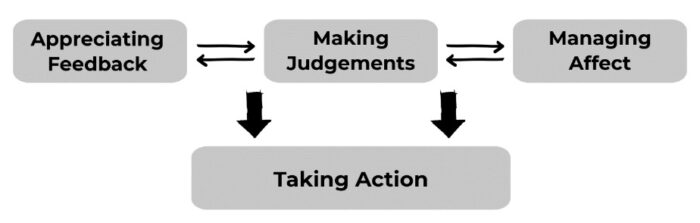

Carless and Boud (2018) designed a student feedback literacy framework (figure 1) to provide a more tangible way of measuring students’ agentic engagement with feedback. Their framework suggests that if students develop their ability to appreciate feedback, make judgements and manage affect, they should then become more competent at taking action in terms of applying feedback to future work and closing the feedback literacy loop (Boud & Molloy, 2013). In this study, the framework is used to show how all four aspects can be developed during a foundation course to improve students’ engagement with peer review as well as their overall feedback literacy. The barriers to active participation are analysed through the theoretical lens of the framework and recommendations are made for a more scaffolded approach to integrating peer review into foundation courses.

Figure 1: Features of Student Feedback literacy (Carless and Boud, 2018)

CONTEXT

The International Foundation Programme (IFP) at the University of Bristol is divided into three pathways: Arts and Humanities, Social Sciences and Law (including Economics, Finance and Management students) and STEM. All students take courses in English for Academic Purposes, but this study will focus on students with an average IELTS score of 5.5-6.5 who attend the IFP Standard EAP unit of Academic Writing. For the final assessment of this unit, students submit a developmental e-portfolio which includes six tasks: Process/Purpose, Compare and Contrast, Cause and Effect, SPSE, Mini Research Report (STEM/EFM) or Discursive essay (ARTS/SSL) and a Reflective Writing task. As well as tutor feedback on a formative draft and final submission of each task, regular peer review is integrated into the scheme of work to encourage students to become active participants in self and peer evaluation (Hoo, Deneen & Boud, 2021). Although in-house materials suggest ways to conduct these peer review workshops, the tutor can adapt existing materials, or devise new activities, to suit their learners’ needs. Many of the materials provided involve a task checklist (see Appendix 1) which relates to the weekly intended learning outcomes or aspects of the assessment criteria.

METHODOLOGY

Participants and data collection

A three-phase triangulated qualitative research method was used to collect data. The first phase involved surveys with two mixed nationality Academic Writing classes (28 students) at the beginning and in the middle of the second teaching block (TB2) of the academic year. One class was from the STEM pathway and the other was an EFM class from the Social Sciences and Law pathway. The first survey focused on students’ experiences of peer review during the first teaching block (TB1) which had mainly involved the use of formulaic task checklists. The second survey was conducted after the same two groups of students had participated in writing circles halfway through TB2 to investigate their attitude towards this more scaffolded and dialogic approach. The group writing circles allowed students to choose their own focus for peer feedback, thereby giving them more ownership of the process. Both surveys consisted of open and closed questions using electronic survey software and could be completed anonymously.

Following the writing circle activity, other more scaffolded and interactive peer review activities were introduced in the second half of TB2, including the use of shared documents to record feedback and inserting comments directly into each other's scripts. To build on the data collected from the surveys, a student focus group and two semi-structured interviews with six students from the STEM and EFM classes were conducted at the end of TB2 to evaluate the interventions and further investigate perceived student barriers to participation in peer review. The student participant information is summarised in the table below:

| Student participants | Total number | Pseudonyms | Data collection method |

| STEM foundation students | 2 | Sally Clive |

Semi-structured interviews |

| EFM foundation students | 4 | Jasper Pam Giles Claire |

Focus group |

Table 1: Overview of student participants

To enhance the validity of the results from the student data, six academic writing tutors were interviewed at the end of TB2 about their own perceptions of the student barriers to participating in peer review and how these challenges could be overcome. An additional question was asked about how these workshops could be scaffolded more effectively to promote active participation. The tutor participant information is summarised in the following table:

| Tutor participants | Total number | Pseudonyms | Data collection method |

| Academic Writing tutors | 5 | Charlotte Richard Molly Melissa Flora |

Focus group |

| Academic Writing tutors | 1 | Clive | Semi-structured interview |

Table 2: Overview of tutor participants

Analysis of data

The transcripts from the student and tutor focus groups and interviews were thematically analysed in accordance with the five steps recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006): a) immerse yourself in the data; b) generate initial codes; c) re-focus the analysis to search for themes or patterns at a broader level; d) review the themes and patterns and refine them; and e) further refine the themes and patterns and name them. Initially, two main codes emerged during the data analysis: factors that facilitate participation in peer review activities and factors that hinder participation. Through further exploration and modification of the codes, it became clear that these two overarching themes could each be subdivided into the categories of cognitive, social, affective and linguistic factors.

The software NVivo was used so that the data from the five different transcripts could be compared, and common themes and patterns identified. This was especially important when comparing student and tutor perceptions of barriers to peer review, as triangulation of the data revealed some key differences in their views of the factors which facilitate and hinder active participation, which will be discussed in the following sections. After the codes and themes had been refined, the data was analysed again from the perspective of the four aspects of Carless and Boud’s (2018) framework for student feedback literacy, which helped to explain some of the patterns that emerged from the data.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Data from student surveys

Responses from the initial survey at the beginning of TB2 (24 responses) included predominantly positive comments about participating in peer review activities and 79% of the students felt that they had benefitted from both giving and receiving feedback, indicating that they valued the cognitive processes involved in reviewing. For example, one student emphasised the role of critical evaluation in peer review:

- The person participating in peer review is required to analyse and evaluate the other's work with critical thought.

However, there were several negative comments relating to a lack of ability to communicate feedback effectively, both when giving and receiving feedback, which suggests that linguistic competence is one of the factors which hinders active participation:

- Sometimes I can't give them feedback because I'm not good enough with language to understand their essay and write comments

- Only receiving feedback from the teacher is helpful. Peer review was so bad because they can't speak English well enough for me to understand.

Data from the second student survey halfway through TB2 indicated a generally positive response to the scaffolded writing circle activity, with over half of the students agreeing that it was more useful than previous peer review activities as they were able to take control of the process and request feedback on specific areas of their work:

- It helped me to get the useful information that I want

- I can ask for how to improve structure of my essay

Overall, 73% said that they had made significant changes to their writing because of peer feedback from the writing circles, which indicates a high level of agentic engagement.

Phase 2: Data from student and tutor focus groups and interviews

In phase two, the qualitative analysis of the transcripts identified some of the same themes that had emerged from the survey responses. Although there was much agreement between the students and tutors about which factors affected active participation in peer review, some significant differences in opinion also emerged, which will be discussed in the following section. The main findings are summarised below, but these will be exemplified with examples from the transcripts in the Discussion section to show how they relate to the four aspects of the student literacy framework (Carless and Boud, 2018).

In response to the question about barriers to peer review, the students focused predominantly on linguistic factors and how their lack of confidence with the language of reviewing prevented them from engaging with the process. Social and affective factors were also mentioned; the former in terms of how a lack of familiarity with their peers affected their motivation to participate and the latter in terms of their perceived lack of usefulness of feedback comments from peers. Although the tutors were in agreement that an underappreciation of the value of peer feedback had a negative impact on participation, they placed more emphasis on cognitive factors, assuming that the complex mental processes involved in evaluating the quality of their peers’ essays could prevent students from actively participating. Affective factors were also raised, namely how unrealistic expectations of producing tutor-like feedback could put students under considerable pressure, which would reduce their motivation to participate.

There were also key similarities and differences between the student and tutor responses to the question about how to increase active participation in peer review. Although both groups of participants agreed that affective factors played a significant role, the specific sub-factors mentioned were different. For the students, increased ownership over the process and accountability for their actions were believed to increase their affective response to peer review, motivating them to take a more active role in the process. In contrast, although the sub-theme of accountability was mentioned briefly in the tutor focus group, greater consideration was given to regular reflection and how encouraging students to reflect critically on their experiences of peer review could lead to more active engagement in future workshops. Both groups also mentioned the value of allowing sufficient time for post-feedback discussion for students to unpack and make sense of peer comments.

DISCUSSION

This section will explain how Carless and Boud (2018)’s framework was used to interpret the main findings from phases one and two, which are summarised in table 3 below. By analysing the data through this theoretical lens, it was possible to make recommendations for each aspect of the framework to increase students’ active participation in peer review as well as improve their overall feedback literacy. Suggestions will be made in terms of material design and classroom practice for future foundation courses.

| Aspect of the framework | Student data | Tutor data

|

||

| Factors that facilitate participation | Factors that hinder participation | Factors that facilitate participation | Factors that hinder participation | |

| Appreciating feedback | Not valuing peer feedback | Not valuing peer feedback or the act of reviewing | ||

| Managing judgements | Lack of confidence with language of reviewing | Lack of complex cognitive skills involved in evaluating | ||

| Managing affect | Positive class dynamics |

Lack of trust between peers | Regular reflection

|

Too much pressure on students / high expectations

|

| Taking action |

Increased accountability / ownership

Post-feedback discussion |

Giving students choice of peer review format Post-feedback discussion |

||

Table 3: Applying Carless and Boud (2018)’s framework to the data

Appreciating feedback

Analysis of the data shows that both students and tutors agreed that one of the main barriers to active participation was the students’ mistrust and lack of appreciation for feedback from their peers. One student commented in the survey that “only receiving feedback from teacher is helpful” while tutor feedback was described as more credible and useful in the student focus group. This view was further corroborated by the following strongly phrased quotations from the tutor focus group:

- Students don't often think other students have any good ideas to offer because they don't know anything.

- Some of mine were very vocal and said there's no point in doing this. I just want your feedback. I do not want the feedback of my friends because they don't know what they're talking about.

Many previous studies on peer review have emphasised the fact that students are often dismissive of peer feedback and are more likely to incorporate teacher feedback into their writing, as they consider the teachers the more experienced and trustworthy experts (Tsui and Ng, 2000; Yang et al., 2006). Indeed, foundation level students often underestimate the value of peer feedback more than undergraduate or postgraduate students, due to the highly authoritative role of the teacher in their previous secondary school context. Therefore, as Carless and Boud (2018) stipulate in their framework, it is crucial to help these students understand that they can be of value to each other to enable a higher appreciation and uptake of peer feedback. One way to achieve this is to build in time to share students’ preconceived ideas and reservations about peer review early in the foundation course, through class discussions and individual tutorials, for example, students could rank the advantages of giving and receiving peer feedback before comparing answers in groups. Banister (2010) explains that these meta-dialogues will not only help to explore the often unknown or underappreciated benefits of peer feedback but could also help to build empathy in the classroom.

In contrast, the data suggests that the students and tutors in this study had different assumptions about the students’ ability to understand the benefits of reviewing. Most tutors assumed that students would dismiss the value of giving feedback to their peers, with one tutor commenting that “students don't recognize that they themselves benefit from giving feedback." However, the students interviewed contradicted this view as they were able to explain the advantages of comparing their work to others:

- For me, it's really helpful because I can find my weakness from others’ draft and compare them to find some advantages and disadvantages.

- You need to find their strength and their weaknesses and compare their draft with myself. It's quite a challenge, but it's really helpful.

This data suggests that students appreciate the benefits of engaging in multiple acts of evaluative judgement more than tutors realise (Nicol, Thomson and Breslin, 2014), and that this awareness can help to promote more active participation. Although they did not always articulate the precise processes involved in reviewing, for example, problem detection, diagnosis, solution generation (Cho and MacArthur, 2011), they were able to appreciate the overall value of comparing their work to others. Therefore, exploring the benefits of reviewing in greater depth, and emphasising the increased understanding of the needs of the reader that this brings, should become an integral part of peer review materials on foundation courses.

Making judgements

As the findings show, both linguistic and cognitive factors affect students’ ability to make evaluative judgements through comparison of their own work with that of their peers or exemplars (Carless and Boud, 2018). The foundation students in this study felt that they often lacked the linguistic resources to provide and interpret feedback, so that even if they could identify strengths and weaknesses in their peers’ essays, they sometimes struggled to articulate their evaluation. One student in the focus group commented that his English “is not so good, so I can’t express what I want or understand what others say” while a student from the survey complained that “peer review was so bad because […] they can't speak English well to understand for me.” Peer review materials, however, can bridge this gap in linguistic competence by including more functional language, for example, a bank of phrases for praising, sensitively critiquing or asking for clarification. This would both increase students’ confidence with reviewing, as well as enable more meaningful dialogues post feedback leading to an overall greater uptake of feedback. According to Banister (2020), integrating these linguistic frames into the materials should encourage learners to take a more active role in peer review.

As well as increasing linguistic support for making evaluative judgements, the findings from the tutor focus group suggest a need to reduce the cognitive load on students so that they are not expected to complete lengthy peer review checklists (see Appendix 1) or produce tutor-like feedback. The comments show that this is especially important at the beginning of a foundation course when students are trying to adjust to the expectations of a UK Higher Education context:

- Maybe checklists should be a guidance document rather than something that they've got to actually actively complete with comments, which puts that onus on them to be an expert marker.

- There’s this expectation that they've got to perform like a tutor. Give feedback to their peer like a tutor would. And it's so much pressure on them.

- But they have to navigate that new terrain and it is also quite a lot to expect of our students when they’re processing so much other information and trying to meet expectations within the higher education environment.

To provide scaffolding for the complex cognitive processes involved in peer review, materials could support students to make holistic judgments about each other’s work, before moving on to analytical feedback on specific aspects of the criteria. Nicol, Thomson and Breslin (2014) suggest that students can be encouraged to make a general assessment of the quality of their peers’ work by comparing two or three peer essays and judging which is better and why. Similarly, Cho and MacArthur (2011) and Winstone and Carless (2019) advocate working in groups of three or four as feedback from multiple peers was found to lead to higher quality revisions of their work. Therefore, working in feedback trios, foundation students could rank peer samples in terms of overall effectiveness or find key similarities and differences between them. Giving students time to make more personal and holistic judgments will help to strengthen their internal feedback mechanism (Nicol, 2019). This ability to generate inner feedback could further be developed by incorporating regular assessment of exemplars into the materials (Carless et al., 2018). By using exemplars from previous cohorts, Nicol, Thomson and Breslin (2014) argue that students can maintain a more detached perspective from the peer review process, thus potentially creating opportunities for more honest and critical evaluations. The use of anonymous exemplars could also help overcome some of the affective barriers discussed in the following section.

Managing affect

The main findings in table 3 suggest that the negative emotions associated with sharing and commenting on each other’s work during peer review workshops are often related to social factors. From the students’ perspective, the main social barrier to active participation was the lack of confidence with each other, which inhibited interaction in the classroom and prevented students from working collaboratively with their peers. Several mentioned the difficulty of engaging in peer review in TB1 before an atmosphere of trust had been established, for example, “you just don’t want to criticize something wrongly because you don't have that confidence between each other” while another observed that in TB2 it was easier to review each other’s work “since we were closer to each other, so we were more open to discuss the ideas and to get new ideas that come out from those discussions.” This theme highlights the importance of creating a sense of belonging at the start of the year so that students feel part of an inclusive academic community, in which they feel comfortable critiquing each other’s work (Tang, Cheng & Ng, 2022).

Building confidence and trust between students is even more important for foundation level students, who are less familiar with the collaborative style of learning advocated by a social constructivist approach (Hussain, 2012). This needs to be addressed both in material design and classroom practice. Tutors can take a proactive role in this process, by creating opportunities for improving class cohesion by encouraging greater intercultural communication at the start of the course. Materials can be designed to include whole class peer review of collaboratively written texts and anonymous exemplars to shift the focus from the individual onto the process of reviewing. As Nicol, Thomson and Breslin (2014) argue, this type of whole class peer feedback, possibly with comparison to the tutor feedback, can help to improve class cohesion at the same time as removing some of the social and affective barriers to peer review.

In contrast to the students’ focus on class dynamics, the tutors seemed more concerned about the negative emotional impact of expecting students to complete feedback synchronously during the workshop. Two tutors commented that they themselves would feel challenged if asked to complete feedback under this level of pressure:

- I think we often ask a lot of our students. I mean, I know that when a student comes to me and says, can you read my essay and give me some feedback I say no, because I can't do that on the spur of the moment.

- Maybe we're expecting too much because there's an awful lot of pressure when other people are there waiting for you to read something.

This last comment reflects another common tutor belief that creating a quieter, private environment would provide students with more space to carry out peer review at their own pace and could help to reduce anxiety about sharing work, thereby facilitating more active engagement (Warschauer, 2022). This could be achieved by students sharing their work online and completing their peer feedback asynchronously before coming to the in person workshop, or by giving them the freedom to find a quiet space in another part of the building outside the classroom to give each other feedback.

Another theme which emerged from the tutor data was regular reflection and the role this could play in lowering the students’ affective filter in order to increase participation. One tutor commented that “reflection is key if they’re going to learn the value of peer review” while another suggested that they could start by “reflecting on what they've learned from doing the peer review of an anonymous script before then reflecting on what they’ve learned from the process of peer reviewing their partner’s work”. The benefits of reflecting critically on experiences of peer review were also emphasised by Kostopoulou and O’Dwyer (2020) in their research on foundation courses. They support the idea that regular reflection is one way to maximise the value and uptake of peer feedback as well as developing students’ ability to appraise academic written work. Therefore, it is recommended that foundation level materials build in time for students to reflect on any negative affective reactions to peer review early in the course to help them overcome socio-emotional barriers. For example, Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle (1988) could be used to allow students to explore their experience of participating in a peer review workshop, or as Hoo, Deneen and Boud (2021) suggest, reflective journals structured around Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (1984) could help to focus students’ attention on key critical incidents related to peer review

Taking action

The recommendations for appreciating feedback, making judgements and managing affect outlined in the previous sections, would all encourage students to take action by applying peer feedback to their future work (Carless and Boud, 2018). However, other affective factors emerged from the data, such as how a heightened sense of accountability could increase the likelihood of students taking action on any peer feedback they receive. Students indicated that they wanted to be held accountable for their actions by being set clearly defined preparation tasks as they found peer review most helpful when “they had to do some preparation for it” and when they “had more pressure to bring in their example essay.” This sense of accountability also appeared to increase with the use of shared documents, accessed by both tutor and peers, which allowed their feedback to be monitored more transparently. The students felt that not only did this public way of recording peer feedback help to increase participation in the classroom, but also encouraged a greater application of feedback to subsequent drafts as “the comments could be looked back on after the class.” Nicol Thomson and Breslin (2014) report on similar positive results with feedback capturing software such as Peer Mark within Turnitin and Peerwise. This aligns with Winstone and Carless (2019)’s claim that one of the main aims of peer review is to seed student autonomy and accountability in preparation for the self-regulation required during undergraduate degree programmes.

Data from the tutor focus group also supported the view that autonomy and accountability could be increased through the use of shared documents:

- The most effective activities used shared documents, so they've got that sort of accountability. They need to show what they're doing, include their comments in there.

- Completing a column on the shared document about the action they're going to take as a result of what their reviewer has suggested gave them a sense of sort of ownership, re-ownership, I guess, over their texts.

As the last comment indicates, including a column on the shared documents for students to complete an action plan after a post feedback discussion with their peers was considered another way to encourage greater uptake of peer feedback. Winstone and Nash (2019) argue that this goal setting stage is essential to developing self-regulation and proactive engagement with feedback. The student participants also valued this dialogic approach and the time given to make sense of the feedback and generate solutions together:

- I think it's really necessary to discuss with the people who give you feedback because well, it will help you understand your feedback more.

- I think after we received the feedback, we should read them first and then have a group discussion.

- If I don't discuss, I may not get a high grade because I just can’t find all solutions by myself.

As well as desiring more responsibility for their actions through increased accountability and opportunities for goal setting, students were more inclined to get involved in workshops that they felt they had ownership over, particularly towards the end of the foundation course. Tutors agreed that handing responsibility over to the students became possible when they could determine the format and focus of the peer review workshops for themselves once they had been exposed to a “repertoire of peer review skills" and “choice of formats.” This could include choosing whether to conduct a holistic evaluation of their peers’ essays, use a criteria-based checklist, create their own student-generated checklist or engage in a more autonomous writing circle activity where students choose the focus of the feedback. Therefore, one of the aims of a foundation course should be to familiarize students with a range of peer review approaches so that they can choose the most appropriate format by the end of the course. Students will then be more confident about seeking targeted feedback on specific areas of their work, providing more constructive feedback to their peers, as well as taking action on the feedback they receive.

CONCLUSION

This exploratory study has shown that with sufficient scaffolding, in terms of material design and classroom practice, foundation students can become more confident and critical reviewers of each other’s work by the end of the course. This helps to improve their overall feedback literacy and support their development as self-regulated learners, so that they can assess their own progress more autonomously at undergraduate level. Despite the obvious limitation of this study in terms of participant numbers, the findings clearly indicate that students recognise the benefits of participating actively in peer review workshops, but that they need support from tutors to overcome the cognitive, social, affective and linguistic barriers that they face in these workshops. The next phase of this project will focus on implementing and evaluating the pedagogical recommendations that relate to the four aspects of the student feedback literacy framework. These interventions will include the following: providing more opportunities for meta-dialogues about the value of giving and receiving feedback; integrating more functional language into workshops; evaluating exemplars and collaboratively written texts; using shared documents to increase accountability and uptake of feedback; and building in more time for discussion and goal setting post feedback. Further action research will then be conducted to determine how much these interventions can increase active participation in peer review workshops and develop foundation students’ overall feedback literacy.

Address for correspondence: catriona.johnson@bristol.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Askew, S. and Lodge, C. (2000) Gifts, ping-pong and loops – linking feedback and learning. In S. Askew, ed. 2000 Feedback for learning. London: Routledge. Ch. 1

Banister, C. 2020. Exploring peer feedback processes and peer feedback meta-dialogues with learners of academic and business English. Language Teaching Research. 27(3), pp.746-764.

Boud, D. and Dawson, P. 2021. What feedback literate teachers do: an empirically- derived competency framework. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. 22 (1), pp 1- 14

Boud, D. & Molloy, E. 2013. Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 38(6), pp. 698-712.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), pp.77-101.

Carless, D. & Boud, D. 2018. The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 43:8, pp. 1315-1325.

Carless, D., Chan, K.K.H., To, J., Lo, M. and Barrett, E., 2018. Developing students’ capacities for evaluative judgement through analysing exemplars. Developing Evaluative Judgement in Higher Education: Assessment for knowing and producing quality work, pp.108-116.

Cho, K. and MacArthur, C. 2011. Learning by reviewing. Journal of educational psychology. 103(1), p.73.

Hoo, H-T., Deneen, C. & Boud, D. 2021. Developing student feedback literacy through self and peer assessment interventions, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. 47:3, pp. 444-457.

Hussain, I., 2012. Use of constructivist approach in higher education: An instructors’ observation. Creative Education, 3(02), p.179.

Kostopoulou, S. and O’Dwyer, F. 2021. “We learn from each other”: peer review writing practices in English for Academic Purposes. Language Learning in Higher Education. 11(1), pp.67-91.

Lam, R., 2010. A peer review training workshop: Coaching students to give and evaluate peer feedback. TESL Canada Journal, pp.114-114.

Molloy, E., Boud, D. and Henderson, M. 2020. Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 45(4), pp.527-540.

Min, H.T. 2006. The effects of trained peer review on EFL students’ revision types and writing quality. Journal of second language writing, 15(2), pp.118-141.

Nicol, D. 2019. Reconceptualising feedback as an internal not an external process. Italian Journal of Educational Research, pp.71-84.

Nicol, D., Thomson, A. and Breslin, C. 2014. Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: a peer review perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(1), pp.102-122.

Nicol, D. 2011. Developing students' ability to construct feedback. QAA Scotland, Enhancement Themes.

Tang, E. Cheng, L. and Ng, R. 2022 “Online Writing Community: What Can We Learn from Failure?,” RELC Journal, 53:1, pp. 101–117.

Tsui, A.B. and Ng, M., 2000. Do secondary L2 writers benefit from peer comments? Journal of second language writing. 9(2), pp.147-170.

Warschauer, M. 2002. Networking into academic discourse. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 1(1), pp. 45-58.

Winstone, N. and Carless, D., 2019. Designing effective feedback processes in higher education: A learning-focused approach. Routledge.

Winstone, N.E. and Carless, D., 2021. Who is feedback for? The influence of accountability and quality assurance agendas on the enactment of feedback processes. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 28(3), pp.261-278.

Winstone, N.E. and Nash, R.A., 2019. 11 Developing students’ proactive engagement with feedback. Innovative assessment in higher education: a handbook for academic practitioners, p.129.

Winstone, N.E., Nash, R.A., Parker, M. and Rowntree, J. 2017. Supporting learners' agentic engagement with feedback: A systematic review and a taxonomy of recipience processes. Educational psychologist, 52:1, pp. 17-37.

Vygotsky, L.S. and Cole, M., 1978. Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard university press.

Yang, M., Badger, R. and Yu, Z. 2006. A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. Journal of second language writing. 15(3), pp.179-200.

Yu, S., & Hu, G. 2017. Understanding university students’ peer feedback practices in EFL writing: Insights from a case study. Assessing Writing. 33, pp. 25–35.

Zhu, W. 1995. Effects of training for peer response on students' comments and interaction. Written communication. 12(4), pp.492-528.

APPENDIX 1: Checklist for Cause and Effect essay

Checklist for Cause and Effect draft 1 |

||

| Y/N/? | Comments: (give examples of effective writing and where it can be improved) | |

Introduction |

||

| Background/context information introducing topic and focus of the essay | ||

| Key terms defined? (if necessary) | ||

Clear purpose, specific map & thesis?

|

||

Main body paragraphs |

||

General to specific pattern?

|

||

Paragraphs flow smoothly (coherence & cohesion)?

|

||

Details in support of each main point

|

||

Appropriate academic sources

|

||

Critical analysis and evaluation (not description) and clear writer’s stance?

|

||

Language |

||

Academic style

|

||

| Range of cause-effect language? | ||

Conclusion |

||

| Summary of main points? | ||

| Restate thesis? (Mirroring the Introduction) | ||

| Future focus? (e.g. implications, predictions, limitations, recommendations) | ||

General Comments |

|

How could this draft be improved? |