Impediments to the Adoption of Subject Specific Reading Strategies in EAP – Exploratory Practice with Hohfeld’s Jural Relations

Neil Allison

University of Glasgow

ABSTRACT

English for Academic purposes (EAP) is increasingly being influenced by theories of literacy and reading to learn, with the EAP practitioner training students in reading skills and strategies that incorporate engagement with disciplinary specifics. However, little is known about EAP practitioners’ and EAP students’ attitudes to disciplinary or subject-specific reading strategies. This study involved a survey of 81 EAP practitioners, and mixed-methods with students on EAP for Law courses to explore the impediments to the adoption of subject-specific reading strategies. To provide tangible context, a reading strategy for law students known as Hohfeld’s Jural Relations is described in detail and employed and evaluated as part of exploratory practice. It is concluded that EAP teachers are sceptical on the importance of subject-specific reading strategies while students are more likely to adopt strategies once they are aware the strategy is a respected means to gain subject-specific understanding. This article will be of particular interest to teachers of EAP for law and law teachers unfamiliar with Hohfeld’s work.

KEY WORDS: reading strategies, EAP, ESAP law; Hohfeld’s Jural Relations; teacher and student beliefs

INTRODUCTION

English for Academic Purposes (EAP) sits as a field within English for Specific Purposes (ESP) and applied linguistics (Hamp-Lyons, 2011, p.89), with much of the application being as an education activity to support and improve students’ language and thus their performance in specific contexts (academic contexts and/or specific academic subjects). The focus in this article is on how we improve students’ reading if university reading is reading to learn not learning to read (Maclellan, 1997). Since much of EAP teachers’ pedagogical activity involves working with students who are not studying linguistics, education, EAP, ESOL, or related fields, to what extent are EAP teachers motivated and equipped to support and improve those students’ performances (their skills in learning)? While there is of course an option for EAP teachers to work more closely with subject teachers, the starting point would still require an acceptance that improving reading as a general skill is insufficient and that an important part of the EAP teacher’s remit is to help students read to learn. An increasingly sizeable literature in education and SFL (second or foreign language, including EAP) views reading as a literacy (for example Barton, Hamilton, Ivaniúc, and Ivanič, 2000; Lea and Street, 2006; Lillis and Scott, 2007; Abbott, 2013), that it is rooted in a need for the reader to interact socially with the writer and the writer’s society. It also incorporates an understanding of power (Lea and Street, 2006, p.8). These arguments about literacy and power make it particularly valuable in widening participation (Lea and Street, 2006), for example for working with international students and those from backgrounds somewhat distanced from tertiary education in terms of academic or social capital.

With numerous arguments, supported by empirical research, proposing more integration of reading education and the development of disciplinary knowledge (e.g. Hunter and Tse, 2013; Hamp-Lyons, p.93) it seems timeous to pursue this line of inquiry. The aims of this research were to explore EAP teacher and EAP student attitudes to academic discipline specific literacy, in particular reading strategies to aid with detailed comprehension and written output. This information will provide teachers with better understanding of potential impediments to students adopting subject specific reading strategies. For example, if an EAP teacher and EAP students did not believe subject specific reading strategies exist, it is highly unlikely they would be developed or adopted. The teacher is unlikely to teach or promote them while students’ beliefs will reject or ignore them because beliefs about learning and improving reading in a foreign language are, like beliefs about any learning, critical to the adoption of new approaches to learning (Alexander et al. 2016). Further, if reading is seen as simple, students will not adopt cognitively challenging reading strategies (Simpson and Rush, 2003).

This study was exploratory, carried out largely as practitioner inquiry over several EAP courses at a Scottish University to gather sequential data. The study also included one survey of 81 EAP teachers in Spring 2019 to capture perceptions on subject specific reading. For the purposes of providing a concrete teaching context to orientate and give meaning to the discussion on academic literacy and the results of this study’s data collection, an application of a specific disciplinary reading strategy and skill is provided – the use of a strategy called Hohfeld’s Jural Relations (‘HJR’) to aid in a vital reading skill: understanding and analysing legal concepts.

CONTEXT – DIFFERENCES IN ONTOLOGY GO BEYOND MERE VOCABULARY DIFFERENCES

Law as a discipline is often labelled a professional science, but also as a liberal art in the US (Arzt, 1988), encompassing several social sciences and humanities. Its position as both profession and academic study is not entirely comfortable and thus it is often positioned by those in the discipline simply as its own unique discipline (Arzt, 1988). Different disciplines, it would be uncontroversial to say, involve different vocabulary, but more than this, different ways of thinking about the world, with assumptions and methods forming a distinct branch of learning (Vick, 2004). To say that vocabulary differs is clearly insufficient; we must be more precise and say that ontology differs, and of course that epistemology differs (a point that the academic literacies movement considers highly important e.g. see Wingate and Tribble (2012). The vocabulary expresses what can exist within a particular discipline or world; what is reality. In philosophy, ontology is ‘the set of things whose existence is acknowledged by a particular theory or system of thought’ (Honderich, 2005, p.634). To give a concrete example, a trust in law is different from general English language trust; however, more crucially, in many civil law systems (contrasted with predominantly common law systems existing in Scotland, England, USA etc.) trust does not exist as a legal concept; thus it can only be approximated in meaning or understanding (Sarcevic, 1997). The language of law is ‘system bound’. De Groot (2006, cited in Scott, 2019, p.40) considers that structural differences between legal systems are the primary problem behind translation; thus it is easy to imagine the comprehension difficulties faced by students from different legal systems when reading law texts.

Working with texts across languages, cultures, and the civil law/common law divide is not the end of the matter. Even within a superficially uniform context such as where the language is the same and the legal systems are closely connected but historically, traditionally, and culturally distinct, there can be a lack of commonality and transferability. English language is used in various legal systems, each with commonalities and distinctions (Lundmark, 2012). For example, within the UK, English and Scottish legal ontologies differ, as exemplified by a critically important concept such as equity (Smith, 1954). So, even if we agreed, for the sake of argument, there were such a thing as British English, there is clearly no such thing as British Legal English. This means strategies when reading legal texts in English need to be applied that do not rely on translation or a hasty search for equivalence in order to analyse the meaning of a legal concepts. Analysing legal concepts is an essential skill of law students and lawyers, as almost every introductory legal textbook will stress.

An approach to (or strategy for) legal analysis, specifically the unpacking of legal concepts to reveal their precise nature, prior to applying typical common law legal analysis processes such as analogical, inductive, and deductive reasoning from court cases (Walker, 1992) is the Hohfeldian framework of jural relations.

EXPLANATION OF HOHFELD AND RELATIONSHIP TO ONTOLOGY

Wesley Hohfeld, an American jurist, created his system in the early 20th century, publishing it in 1913 (Hohfeld, 1913) and over 100 years later his work is highly valued by legal philosophers (Brown, 2005). Hohfeld’s framework, set out in table 1, is a means of understanding legal relations and the rights of the subjects of law. It is important to state that his interest was not in translation, or even explicitly in linguistics. Hohfeld was concerned that legal rules, the essence (in a philosophical sense) of legal concepts were poorly articulated by drafters, lawyers, and scholars, and that this could even result in contradictions, contradictions that could be resolved with a more precise understanding of the relationships between subjects (Clark, 1922). In particular, use of the word right was imprecise. Hohfeld wanted to reduce this lack of precision. He saw law as a series of fundamental relationships and that legal concepts and their constituent rights, responsibilities and so on could be set out clearly and underpinned by formal logic. The relationships are of mutual entailment and he called them ‘fundamental’ because they underly all legal concepts, meaning that these 8 terms construct the world of legal rules, describing how the subjects (or societal agents) affect each other in law; these are legal (or jural) relations (Corbin, 1920). Analysing a legal concept through relations (though not exclusively, it is important to point out, since Hohfeld’s system is not intended to cover everything about the interpretation of a concept) can be illustrated with the legal concept property; if one lived alone on a desert island, there would be no property in a legal sense since there are no entitlements; no relations (di Robilant and Syed, 2018).

The top row items of table 1 are generally known as rights, but Hohfeld saw only the first one (top left) as a true right. To understand the terms in the top row, one must refer to the correlative below each. So, a true right requires there to be another who owes a duty to the holder of the right. The right holder would have a claim against the duty holder if that duty holder failed to protect the right. A contract is an example of where claim rights and the correlative duties are established: a right to performance after making payment, a duty to perform after receiving payment, and a legal claim for either’s failure. By contrast, a liberty right is a freedom or permission in that there is nothing illegal about performing the relevant action but the correlative is no right (not a duty), which means if you as the liberty holder failed to perform your desired action no one will be at risk of a claim; for example, in the case of freedom of expression, no one need assist you to realise your freedom and any actions preventing your expression would not be illegal for the reason that they stopped your expression (though they might break some other law such as through criminal assault, or theft in the case of someone stealing your megaphone). Arguably, human rights are particularly well served by Hohfeld’s system as a means to improve analysis of their true nature (Sucharitkul, 1986).

Turning to secondary rights, the term potential rights is informative; the duty to perform jury service, for example, is not a duty but a potential duty if the relevant state body has a power to call residents for jury service; as a correlative, those citizens are liable to the power; only once the state body makes a decision to operate that power does the relationship become one of right and duty. By contrast, non-residents would be immune from the state’s power, and thus the state has a disability (or no power) (Nyquist, 2002). Fiorito and Vatiero (2011) see this focus on the relations between Government and citizens as being particularly informative on potential rights.

HJR is appealing because it uses terminology understandable in the legal profession and enables us to move away from the abstract to the concrete, so that we can analyse a legal relationship in its constituent parts, step by step, and in a standardised way. Also, from an onotological perspective, it helps us consider essence and the degree of essence (Honderich, 2012); for example, which features (in Hohfeld’s case, which relations) are relative or context dependent, which are always necessary, and even which are unique.

The next section will consider EAP and Education’s understanding of reading strategies and towards the end of that section, how HJR can be seen in terms of reading strategies.

READING STRATEGIES AND HOHFELD AS A READING STRATEGY

A problem with identifying reading strategies is the confusing terminology used in the literature. Alexander et al. (2016) in their ‘retrospective and prospective examination of cognitive strategies’ highlight this. Their attempt to provide clarity is by making the distinction between conscious and unconscious approaches as the key test; a conscious approach is a strategy. The problem is that with this definition, automaticity or use of a strategy subconsciously would take it outside of the definition. Expert readers often do not think of how they read, yet we would not say they have no strategies (Shanahan, Shanahan, and Misischia, 2011). For the purposes of this study, a strategy is defined as being an approach to reading that is a means to an end but is never an end in itself, whether or not it has been automatized into skilful strategy use. Skill, however, can be an end in itself. This would distinguish between skimming and reading for gist: skimming is not an end in itself so it is a strategy to assist with the skill of reading for gist. Literacy in this context is a combination of strategies and skills that enable understanding at whatever level is necessary for a task.

Having distinguished between strategy and skill, a problem remains. The lion’s share of skills and strategies are the same and transferrable for all reading e.g. phonics, reading for main idea, inferring, identifying argument or persuasion, skimming to help understand gist, and so on. Perhaps this is the common core perspective (Bloor and Bloor 1986, cited in Hyland, 2002); the common core view is a pillar of English for General Academic Purposes (Carkin, 2005). If we claim that a subject-specific example of a skill is analysing legal concepts, as was mentioned in section 3, this could still be viewed by an EGAP teacher as part of a general skill of understanding details or understanding concepts. A standard strategy to understand concepts or details is to use a dictionary. A general EAP teacher might work on effective dictionary use in class and then expect a law student from their class to use their own background knowledge and add the use of subject specialist dictionaries outside class, but they would still imagine the student would apply the common core ideas from class. Indeed, is use of a specialist dictionary not just a common core strategy? Consider HJR in the same terms of general – specific EAP. HJR is actually a form of analogising, which as an umbrella term is a general strategy, not a subject-specific one. Analogising aids us in the skill of reorganising and reinterpretation, to use Nuttall’s terminology (1996). Is HJR a minor adaptation of a common core strategy? This article argues not. Analogising does not do justice to the action of unpacking and repacking concepts. As Hyland and Shaw (2016, p.197) argue, a key finding of tertiary EAP is that teachers should ‘not only unpack the technicality and grammatical metaphor of textbooks and readings, but, critically, [must] repack them. In other words, if we analogize or explain technical meanings into everyday language, we cannot abandon students there. We need to guide them back into using the specialized knowledge and language of their disciplines.’

We can see how this works with HJR if we take an example of the term ‘trust’ used earlier.

Below is a synthesis of a definition from Halsbury’s Laws of England and the website of a law firm, Ogiers, specialising in Trusts.

Settlors divest themselves of legal ownership. Legal title to the trust assets is vested in the trustee and beneficial ownership to the beneficiary, although a protector may be appointed to control the operation of the trustees. There is an equitable obligation which binds the trustees to deal with the trust property (which is owned by them as a separate fund) for the benefit of beneficiaries who have an equitable proprietary interest in the trust property. In a discretionary trust, the trustee has a discretion on who benefits from the trust fund. (Halsbury’s Laws of England, 98, 1, 2019; Ogiers, 2016)

Analysing the relations and unpacking the concept, we could say

- The Settlor can dispose of property to a trustee.

- The Settlor can name a protector.

- The Settlor shall name beneficiaries.

- The Trustee must manage property for beneficiaries.

- The Trustee must follow protector’s instructions

- The Beneficiary might not receive trust property (in case of discretionary trust).

- The Trustee can to a large extent act freely in day to day managing of property in respect of settlor and beneficiary.

Indeed, if we were a practising solicitor speaking to a client, this might be the very language we should use. What must happen next, though, is that we can repackage into the specialized knowledge of the discipline, which might look like this, using HJR:

- Settlor has liberty to dispose of property to a trustee.

- Settlor has liberty to name a protector.

- A protector has power to direct trustee.

- Settlor has liberty to name beneficiaries.

- Trustee has a duty to manage property for beneficiaries.

- Trustee has a duty to follow protector’s instructions.

- Beneficiary has no right to receive trust property (in case of a discretionary trust).

- Trustee has liberty in day to day managing of property in respect of settlor and beneficiary.

In addition to this process involving the skill of reinterpreting (Nuttall, 1996), HJR is a strategy that promotes deep processing (and therefore arguably more effective retention) as opposed to surface processing (Alexander et al. 2018, p.11). It is quite likely that pedagogy is what inspired Hohfeld in constructing his framework i.e. improving legal teaching (Hull, 1995, p.257). HJR has become an important contribution to legal philosophy (jurisprudence) but it was designed for teaching. Since the foundation of understanding law is understanding legal concepts, HJR is a highly effective approach to explicating the ontology of law.

Explicating the ontology of law, or understanding legal concepts is clearly essential for law students and lawyers. Despite this fact, it is clear that many users of legal language struggle with limited strategies; strategies limited to subject specific dictionaries and/or translation (for a lengthy discussion of issues in translation see Kozanecka et al., 2017 particularly from p.77). Why has HJR not previously been labelled and promoted as a subject-specific reading strategy? A review of different materials relating to law and/or ESAP provides an idea. It appears that strategies reviewed by writers on ESAP and general education research such as legal English literacy omit HJR, seeing reading and writing more from a broader perspective or common core lens (as suggested by a search of 95 articles citing Deegan's 1995 work on law reading strategies). Perhaps they have been influenced by linguistics and by genre studies which are generally dominant lenses in ESP (Alousque, 2016; Wingate and Tribble, 2012). An interesting comparison is with published textbooks on academic legal skills aimed at law students such as Hanson (2009); these provide genre guidance to help read texts such as law reports, but usually do not link their guidance to education and literacy literature. HJR as a pedagogical tool is, however, occasionally mentioned in legal education literature (e.g. Hull, 1995; Nyquist, 2002) but again with little link to education and literacy research.

AIMS

The aims of this scholarship were to understand more about impediments to the adoption of effective reading strategies, particularly subject specific strategies, by exploring views of teachers and beliefs of students. To my knowledge, such research has not been carried out before though Simpson and Rush (2003) highlight its importance. There is plenty of research on factors that influence students use of reading strategies such as self-efficacy (e.g. Guthrie and Wigfield 1999) but not specifically their openness to learn new and subject specific reading strategies.

- What are EAP teachers’ attitudes to teaching reading in different disciplines including their attitude to subject specific reading strategies;

- To what extent do EAP students in subject-specific contexts expect teachers to help them understand the subject;

- Do students believe in and believe themselves open to subject specific reading strategies;

- What might encourage adoption of HJR?

METHODOLOGY

In terms of a model that takes account of the aims of the teacher researcher in improving their own teaching, in the present case how to improve uptake of subject-specific reading skills, this research was exploratory practice (Allwright, 2003). In terms of paradigms, it was largely pragmatic (Avramidis and Smith, 1999) to obtain data that was real, although there was an element of interpretivism with subjective (individual, cultural, context dependent and relative) elements. Indeed, this was seen as a value of the approach since the underlying assumption is that attitudes or beliefs are critical to the adoption and application of reading strategies (Alexander et al., 2018). The size of sample of those taking part was, consequently, not of primary importance. Nonetheless, the convenience sample of students was typical of a UK university EAP environment. In the teacher survey, the self-selection of EAP teachers may make this sample less representative of those involved in EAP more broadly.

Due to the presence of beliefs in the research questions, mixed methods was chosen: group interviews with students, and surveys of teachers and students were administered. De Vaus and de Vaus (2013), when considering surveys eschew the quantitative/qualitative in favour of the perspective of structured and unstructured data e.g. unstructured qualitative data. Using their terminology, unstructured data and structured data were taken: in the case of the former, open questions, while a structured approach was taken to allow for quantification such as in teacher attitudes to reading strategies; teachers gave a Likert scale ‘value’ to how important they perceived them to be. Systematic qualitative type questions were guided by Lietz's (2010) advice on the design of such questions. Most tools allowed for deductive and inductive analysis, though there was more emphasis on the former.

There were essentially five stages to this research including the background stage. Ethical approval was gained twice to account for the different contexts and collection methods as they developed.

DATA COLLECTION STAGES

Participants were either teachers involved in EAP or law students (both pre-sessional i.e. studying full-time academic English before commencing university subject programmes, and in-sessional post-graduate student i.e. already studying on university subject programmes). Their English levels were between B2 and C1, IELTS 5.5 to 7).

Background or pre-data gathering stage:

This was the stage when the puzzle (to use Allwright’s terminology 2003, p.121) arose. HJR was taught as a reading strategy in Autumn 2017 and Autumn 2018 with international LLM students (N 21; N17, English level B2 and C1). In each year the students were canvassed via google forms, anonymously, on whether they would use HJR in the future. Question asked was:

- Would you use Hohfeld’s jural relations as a reading strategy in the future?

Of 38 responses, 4 were yes, 14 maybe, 20 no.

Common additional responses came under a cost/benefit theme e.g. ‘it’s too difficult’; ‘it takes me a long time’, ‘I don’t find it useful’; ‘I have more useful approaches’; ‘I’m not sure why it’s good, and it’s slow’.

This set the ground, or ‘puzzle’ for the subsequent four sequential stages carried out in 2019, primarily hoping to provide insights on how to make the strategy teaching more effective. The choices of respondents was based primarily on convenience or opportunity.

Stage 1

A survey (Appendix A) was piloted with three EAP colleagues, refined, and sent out in Spring 2019 on the BALEAP mailing list (a subscription email list for researchers, managers, and teachers in EAP) inviting responses from teachers involved in EAP regarding attitudes to subject specific reading strategies.

Stage 2

In Summer 2019, pre-sessional students on a law-specific five-week course were invited to give views via a log/diary (Appendix B) that contained unstructured and structured qualitative data gathering questions on their expectations of EAP teachers on a pre-sessional law course and on the existence of subject specific reading strategies; these students had IELTS reading level of 6 to 6.5. Students first took part in a group interview to clarify the meaning of key concepts reading strategies and detailed understanding. The methods of this research had been trialled three months earlier with a EGAP course to uncover any difficulties in understanding.

Stage 3

In Autumn 2019, international LLM students participated in surveys on their attitudes to subject-specific reading strategies. Data were collected on the first day of this optional EAP for Law in-sessional course. This research was carried out in the light of results of stage 2 to investigate whether students were open to learning reading strategies specific to law.

Stage 4

In Autumn 2019, law students (international) at undergraduate and post-graduate level (B2 and C1 level) were taught HJR as a reading strategy and asked to provide feedback on their understanding of its purpose, value, and whether they would use it. These results were compared to previous data (from 2017 and 2018 – referred to above in background stage). Questions were based on Alderson (2000).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Stage 1 teacher data results:

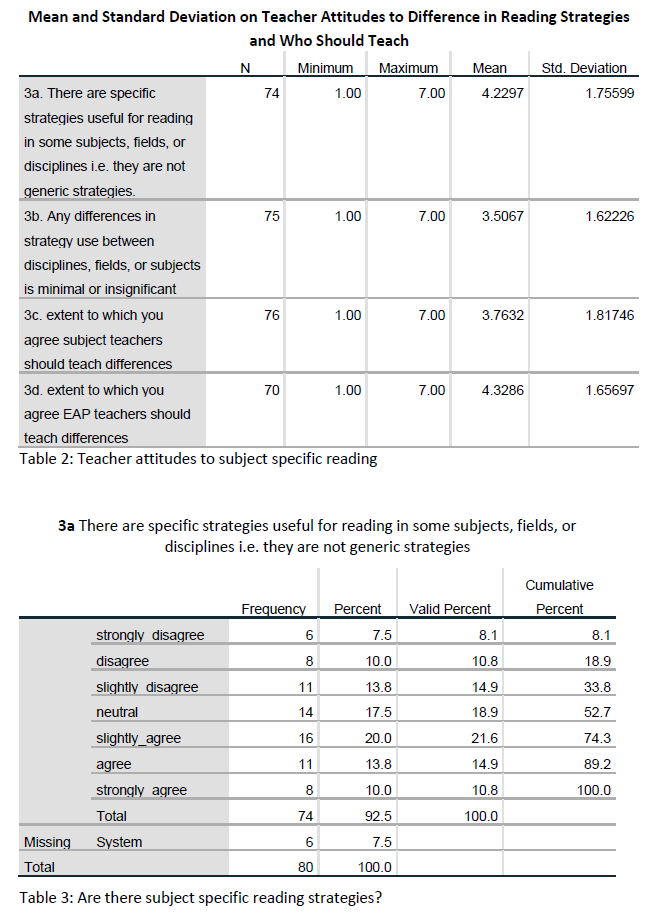

Firstly, respondents indicated their context. There were 81 respondents, all falling into EAP or academic literacy in either teaching duties or disciplinary specialism. Teachers were asked the extent to which they agreed (1-7, or don’t know) with the statements in table 2 regarding subject specific reading. For statement 3a – that there are specific strategies useful for reading in some subjects, fields, or disciplines – the mean score is slightly above 4, 4 being neutral or on the fence.

Table 3 provides more detail on question 3a. It can be seen that 39 out of 74 (52.7%) responses disagreed or were neutral on statement 3a ‘there are differences between strategies by subject’. If we consider only the respondents who said that they teach ESAP, there were 31 responses in this category and only 14 agreed i.e. 45% of ESAP teachers agree there are differences between strategies by subject.

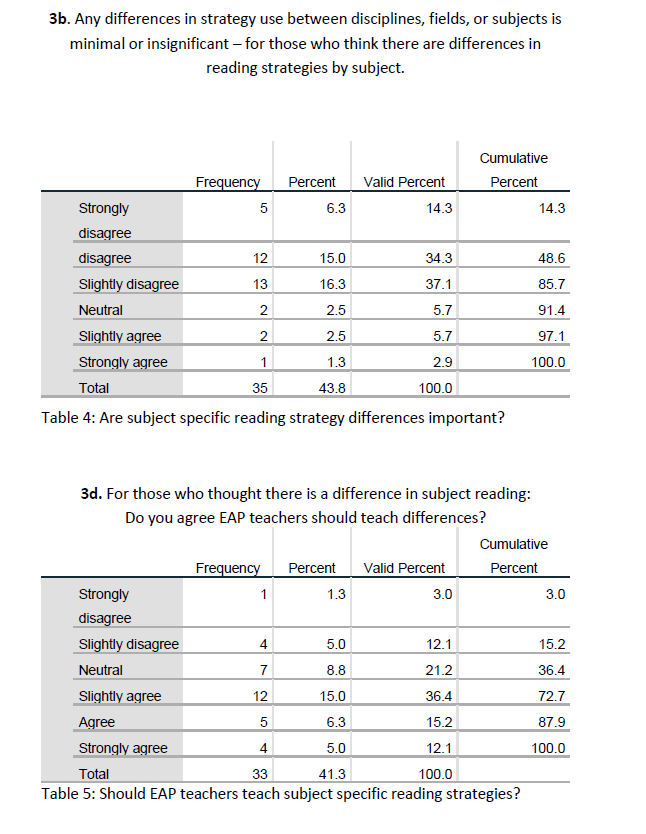

If we consider all 35 respondents who feel there are subject specific reading strategies, we can assess the degree to which they think these differences are important. Table 4 shows that of the 35 responses, 30 consider the difference to be important.

Combining information from tables 2-4 we can thus report that only 30 of 74 respondents consider differences in reading strategies by subject exist and are important. Of these 30, 21 believe EAP teachers should teach specific ways of reading for a subject (total of teachers agreeing to some extent – see table 5); thus of our total sample of 81 teachers who responded to the survey, 21 (or just over a quarter) think EAP teachers should teach specific ways of reading for a subject.

Stage 1 teacher data discussion

This survey was self-selecting. However, we might speculate on what type of EAP teachers are more likely to complete it and whether they are part of a more stable and motivated sub-sample. It is of clear importance to ask whether the approximately 25% of EAP teachers in this survey who seem inclined to teach subject-specific reading strategies, assuming they feel they have the opportunity, are representative of university EAP provision. It is logical to assume that those who do not particularly believe there are different ways to read particular subjects, or if there are, that those differences are minor, are quite unlikely to teach subject specific reading strategies or indeed encourage students to work on these themselves, unless it is by accident.

Bearing in mind the increasing perception over the last ten years of the importance of subject literacy in high school education literature (e.g. Moje, 2008; Shanahan and Shanahan, 2008), tertiary education literature (e.g. Brozo, Moorman, Meyer, and Stewart, 2013), and second language literature (e.g. Rose and Martin 2012; Hyland, 2002 specifically in EAP), this could be seen as a barrier to EAP teachers’ preparedness for promoting literacy.

There were some noteworthy remarks in the open question/free text part of this section of the survey. One respondent, for example, stated that one reads mostly in the same way but the vocabulary is the issue. This would appear to contrast markedly with the remarks in Section 2 regarding ontology and the understanding of the meaning of words in a discipline being critical to being literate. If a student brings subject knowledge and need only translate, this may merely be vocabulary, but in law this is clearly not the case; legal concepts (vocabulary) are not learned by reading a dictionary (specialist or otherwise) but by linking meaning to the appropriate primary source and interpreting by a means recognised by that legal jurisdiction. Admittedly, some general academic words can likely be learned from a dictionary, and medical words, or engineering words from specialist dictionaries, or translated without major difficulty.

One respondent, who believed there are subject specific reading strategies and differences are important referred to Rose and Martin (2012): ’while the broad overarching strategy of genre awareness is common to each discipline, the very nature of genre pedagogy literacy assumes that empowering students to notice the particular features of a given text is what enables understanding. As such, each particular discipline achieves its uncommon sense meaning in a particular way and that way should/must be highlighted for increased student comprehension.’

In other free text responses related to questions 1 to 4 above, 8 teachers made explicit reference to the value or importance of working with subject specialists to improve teaching of reading in EAP.

Stage 2 – Student Diaries/Logs Results and Discussion

Stage 2 data were collected from 20 students, mostly East Asian, over the five weeks of a pre-sessional English for Law course via a diary/log for students reflecting on reading attitudes throughout the course, with a particular focus on student beliefs about subject knowledge influencing reading comprehension. The pre-sessional course employs introductory level legal texts such as sections from textbooks, many recommended by the university Law School specifically for the course.

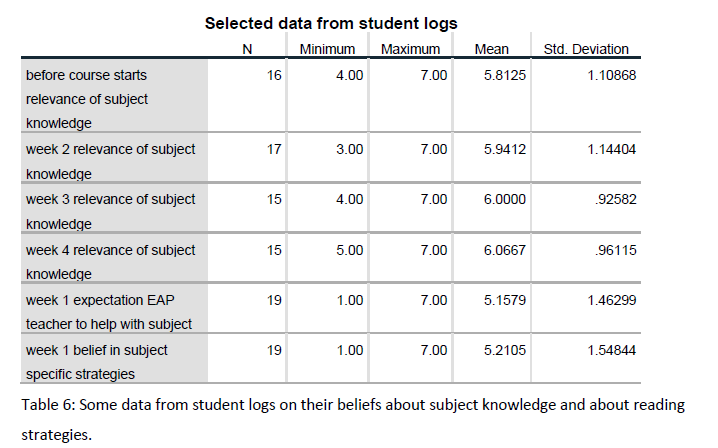

Structured qualitative data showed that students considered subject knowledge/background knowledge to be highly relevant to how well they understood the texts (table 6). They also stated in week 1 that they felt EAP teachers should help with subject knowledge and word meaning (note that students during stage 2 of this research were not exposed to HJR) (table 6). Students also stated that they believed there were subject-specific reading strategies (table 6). Free text responses in student logs were short enough to be capable of manual inductive and deductive analysis revealing the perceived importance of developing subject expertise to read better e.g. ‘I think we now need to learn subject knowledge’ and ‘Difficulty because words don’t translate in law’. 12 students explicitly raised one or other issue.

Stage 3 –LLM students views on subject specific reading strategies on EAP for Law course.

In September 2019, 43 Law Masters’ students (of various nationalities with an approximate balance between European and East Asian, of English level B2-C1) were asked the following question after being given examples of typical reading strategies such as skimming, scanning, note-taking, translating etc.

Question: To what extent do you agree with this statement about reading in English: I would find it useful to learn new ideas for reading strategies/approaches?

Over 70% of students agree or strongly agree that it would be useful to learn reading strategies from the course they were being introduced to (an EAP course for law students).

Stage 4 – Return to original puzzle: in the light of above results, could I improve uptake of HJR by students on an EAP for law course.

The final stage involved bringing the study to a focus on the original puzzle – why were students who were on their programmes, who in theory were ready for subject specific reading strategies, not using HJR?

LLM students (15) and law undergraduate students (7) were separately taught HJR and invited to participate in a survey and group interview. This time HJR was presented explicitly as a subject specific reading strategy (a legal method, so to speak) and students shown results from the survey from stage 3.

The following questions were used, adapted from (Alderson, 2000, p.365)

- What was the main point of the lesson?

- When would you use the information or ideas referred to in 1 above?

- How would you use it – e.g. provide an example?

- Would you use it in the future?

These questions were designed to elicit the four essential elements of reading strategies: declarative knowledge (know them), procedural (know how they work – how to use), conditional knowledge (know when to use), and motivation (believe they are useful).

All 12 students who participated (7 from LLM, 5 from undergraduate) demonstrated understanding of the aims of the strategy – to develop ontological knowledge of law/to understand in detail and analyse legal concepts – and the procedure and when to use them. All (100%) said they would use the approach. Although a small sample, this is highly encouraging and contrasted markedly with 2017 and 2018 where 4 out of 38 (11%) said they would use the strategy, the main change being the explicitness of the strategy as a subject specific one.

The interview highlighted two key influences 1. the strategy was not too complicated, and more importantly 2. the strategy was part of learning the subject, as they perceived i.e. not a suggested approach but rather a correct way/method to understand content (perhaps even meaning they saw it as a subject skill rather than a generic strategy).

COMMENTARY

These results highlight beliefs of teachers and students in an second language academic environment as regards subject-specific reading strategies. Only around 40% of EAP teachers believe that there is importance in the different ways we read in particular subjects, while only around 25% believe EAP teachers should teach differences/specific strategies for subject reading. We would have to speculate on how the remaining 75% of teachers would or do approach in-sessional or subject specific pre-sessional courses, and so more detailed research using clearer or specific examples of contexts would be extremely interesting. It is certainly noteworthy that of the 31 respondents who indicated they teach ESAP, only 14 agree there are subject specific reading strategies. Teachers exclusively involved in pre-sessional or general EAP courses might have little opportunity for subject specific reading, even if they believed there were important differences, but one might assume ESAP teachers have this opportunity.

Although the term ‘strategy’ can prove ambiguous, the survey was piloted and examples were provided to standardise the interpretation. It is remotely possible that subject specific reading strategies such as HJR could be interpreted by some as generic since they could fall under umbrella terms such as paraphrasing, reformulating, and/or analogising. While it is self-evident that reading in law and reading in history and biology will involve many common cognitive processes and cognitive strategies, they will unarguably involve different ontological orientations, with different views of reality, different roles of argument and the means of argument, and so on, aside from any wider social or cultural assumptions and relations between writer and reader. How do EAP teachers view this problem as treatable? HJR focuses particularly on the specific ontology of law. Should subject teachers teach this? Perhaps, but would it not be the responsibility of an EAP in-sessional teacher to, at a minimum, investigate or show an interest. Based on the reported beliefs of the EAP respondents on subject teachers teaching subject-specific reading, the average score of ‘do you agree subject teachers should teach’ was lower than that for EAP teachers teaching, suggesting that this may not currently happen e.g. that EAP teachers are not sufficiently turning their attention to the issue in the first place. An interesting contrast is with students’ expectations of EAP teachers e.g. in stage 2 where the average student score was 5.15 (compared to 4.32 for teachers in stage 1); students tend to expect a level of support from EAP teachers to subject specific reading that EAP teachers show lower willingness to engage with.

With the original puzzle being about adoption of subject-specific reading strategies, results from this study are particularly illuminating. Explicitly linking of a reading strategy to its position as a disciplinary learning tool would appear to influence uptake. Since it is believed students are more likely to adopt strategies and even exert serious effort to using them if they view the type of knowledge involved in a text as complex (Alexander et al., 2018), emphasising ontological difference and complexity would be valuable.

CONCLUSION

This article has described key results from a survey of 81 EAP teachers’ attitudes to subject specific reading strategies and exploratory practice carried out with university students, gathering views of the relevance of subject knowledge to comprehension and attitudes to subject-specific reading strategies. In doing this, it has set out a subject-specific reading strategy for legal reading known as Hohfeld’s Jural Relations which should prove useful to ESAP teachers of law. However, the results of the survey suggest a majority of EAP teachers are sceptical on the existence and/or importance of subject specific reading strategies, which would clearly affect the likelihood strategies such as HJR would be taught. Results also indicate that even were EAP teachers to teach such strategies, student uptake would be influenced by the degree to which they see them as an integral part of learning the subject, which, to use Shanahan, Shanahan, and Misischia's (2011) terminology, would require students being aware of the difference between ‘content area reading’ and ‘disciplinary literacy’, the latter including the habits of mind such as thinking and reasoning: ‘deep knowledge of disciplinary content and keen understanding of disciplinary ways of making meaning’ (Fang, 2012, cited in Buehl, 2017). HJR is not an essential disciplinary skill but it is a strategy that directly aids the essential disciplinary skill of analysing legal concepts and their essence (in this case, their rules). There is a risk, if we do not sufficiently justify the strategies we teach, that students will avoid strategies that are taught. As Kirschner and van Merriënboer (2013) observe in their discussion on digital literacy, learners may choose approaches to reading that they prefer, not what is best (2013, p.177).

Academic communication, as has been extensively considered by some writers as being about power, equality, and access to social justice (e.g. Moje, 2007) and in order to gain access and then challenge ways of thinking, one must understand the privileged or dominant ways of thinking. Anecdotally, one still hears remarks from academics in education who think students need to work it out for themselves. For example, in a law context Christensen (2006, p.606) cites Stratman’s (1990) research in the US that legal educators believe students arrive with ‘intact literacy’ and believe this literacy can be transferred to legal texts.

While this article concludes the EAP teachers should assist students in subject literacy including subject specific reading strategies, it does not present a solution on how EAP teachers are to gain the recommended knowledge to enable disciplinary literacy support, other than providing a tool for ESAP law teachers. This article does recommend EAP teachers find the desire, if they do not have it already, to start to learn. This might include, as several respondents to the teacher survey recommend, working more closely with disciplinary experts to create instruction that promotes disciplinary literacy.

Address for correspondence: neil.allison@glasgow.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Abbott, R. 2013. Crossing thresholds in academic reading. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. 50(2), pp.191–201.

Alderson, J. C. 2000. Assessing reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alexander, P., Peterson, E., Dumas, D. and Hattan, C. 2018. A retrospective and prospective examination of cognitive strategies and academic development: where have we come in twenty-five years? In: O’Donnell, A. ed. The Oxford handbook of educational psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Allwright, D. 2003. Exploratory practice: rethinking practitioner research in language teaching. Language Teaching Research. 7(2), pp.113–141.

Alousque, I. N. 2016. Developments in ESP: from register analysis to a genre-based and CLIL-based approach. LFE: Revista de Lenguas Para Fines Específicos. 22(1), pp.190–212.

Arzt, D. E. 1988. Too important to leave to the lawyers: undergraduate legal studies and Its challenge to professional legal education. Nova Law Review. 13, p.125.

Avramidis, E. and Smith, B. 1999. An introduction to the major research paradigms and their methodological implications for special needs research. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. 4(3), pp.27–36.

Barton, D., Hamilton, M., and Ivanič, R. 2000. Situated literacies: reading and writing in context. London: Routledge.

Brown, V. 2005. Rights, liberties and duties: reformulating Hohfeld’s Scheme of Legal Relations? Current Legal Problems. 58(1), pp.343–367.

Buehl, D. 2017. Developing readers in the academic disciplines. 2nd ed. Portland: Stenhouse Publishers.

Carkin, S. 2005. English for academic purposes. In Hinkel, E. ed. Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 85-98.

Christensen, L. M. 2006. Legal reading and success in law school: an empirical study. Seattle University Law Review. 30 (3), p.603.

Clark, C. E. 1922. Relations, legal and otherwise. Illinois Law Quarterly. 5, p.26.

Corbin, A. L. 1920. Jural relations and their classification. Yale Law Journal, 30, p.226.

de Vaus, D. and de Vaus, D. 2013. Surveys in social research. 6th ed. London: Routledge.

Deegan, D. H. 1995. Exploring individual differences among novices reading in a specific domain: the case of law. Reading Research Quarterly. 30(2), pp. 154-170.

di Robilant, A. and Syed, T. 2018. The fundamental building blocks of social relations regarding resources: Hohfeld in Europe and beyond. In: Balganesh, S., Sichelman, T. and Smith, H. E. eds. The legacy of Wesley Hohfeld: edited major works, select personal papers, and original commentaries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.18–07.

Fiorito, L., and Vatiero, M. 2011. Beyond legal relations: Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld’s influence on American institutionalism. Journal of Economic Issues. 45(1), pp.199–222.

Guthrie, J.T. and Wigfield, A. 1999. How motivation fits into a science of reading. Scientific Studies of Reading. 3(3), pp. 199-205.

Halsbury’s Laws of England 2019 vol 98, para 1. [Online]. [Accessed 18 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.lexisnexis.co.uk/products/halsburys-laws-of-england.html

Hanson, S. 2009. Legal method, skills and reasoning. London: Routledge.

Hamp-Lyons, L. 2011. English for academic purposes. In: Hinkel, E. ed. Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning. London: Routledge, pp.89-105.

Hohfeld, W. N. 1913. Some fundamental legal conceptions as applied in judicial reasoning. The Yale Law Journal. 23(1), pp. 16-59.

Honderich, T. 2005. The Oxford companion to philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hull, N. E. H. 1995. Vital schools of jurisprudence: Roscoe Pound, Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld, and the promotion of an academic jurisprudential agenda, 1910-1919. Journal of Legal Education. 45(2), pp.235–281.

Hunter, K. and Tse, H. 2013. Making disciplinary writing and thinking practices an integral part of academic content teaching. Active Learning in Higher Education. 14(3), pp.227–239.

Hyland, K. 2002. Specificity revisited: how far should we go now? English for Specific Purposes. 21(4), pp.385–395.

Hyland, K. and Shaw, P. 2016. The Routledge handbook of English for academic purposes. London: Routledge.

Kirschner, P. A. and van Merriënboer, J. J. 2013. Do learners really know best? Urban legends in education. Educational Psychologist. 48(3), pp.169–183.

Kozanecka, P., Trzaskawka, P. and Matulewska, A. 2018. Methodology for interlingual comparison of legal terminology: towards general legilinguistic translatology. Comparative Legilinguistics. 31, pp. 167-172.

Lea, M. R. and Street, B. V. 2006. The ‘academic literacies’ model: theory and applications. Theory Into Practice. 45(4), pp.368–377.

Lietz, P. 2010. Research into questionnaire design. International Journal of Market Research. 52(2), pp.249–272.

Lillis, T. and Scott, M. 2007. Defining academic literacies research: issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy. Journal of Applied Linguistics. 4(1), pp.5–32.

Lundmark, T. 2012. Charting the divide between common and civil law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maclellan, E. 1997. Reading to learn. Studies in Higher Education. 22(3), pp.277–288.

McNeil, L. 2012. Extending the compensatory model of second language reading. System. 40(1), pp.64–76.

Moje, E. B. 2007. Chapter 1 Developing socially just subject-matter instruction: a review of the literature on disciplinary literacy teaching. Review of Research in Education. 31(1), pp.1–44.

Moje, E. B. 2008. Foregrounding the disciplines in secondary literacy teaching and learning: a call for change. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 52(2), pp.96–107.

Nuttall, C. 1996. Teaching reading skills in a foreign language. MacMillan Education.

Nyquist, C. 2002. Teaching Wesley Hohfeld’s theory of legal relations. Journal of Legal Education. 52( 1/2), pp. 238-257.

Ogiers. 2016. The use of trusts in Jersey [Online]. [Accessed 18 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.ogier.com/publications/the-use-of-trusts-in-jersey

Rose, D. and Martin, J. R. 2012. Learning to write, reading to learn: genre, knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney School. Sheffield: Equinox.

Sarcevic, S. 1997. New approach to legal translation. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Scott, J. R. 2019. Legal translation outsourced. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shanahan, C., Shanahan, T. and Misischia, C. 2011. Analysis of expert readers in three disciplines: History, Mathematics, and Chemistry. Journal of Literacy Research. 43(4), pp.393–429.

Shanahan, T. and Shanahan, C. 2008. Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review. 78(1), pp.40–59.

Simpson, M.L. and Rush, L. 2003. College students’ beliefs, strategy employment, transfer, and academic performance: an examination across three academic disciplines. Journal of College Reading and Learning. 33(2), pp.146–156.

Smith, T. B. 1954. English influences on the law of Scotland. The American Journal of Comparative Law. 3(4), pp.522-542.

Sucharitkul, S. 1986. Multi-dimensional concept of human rights in international law. Notre Dame Law Review. 62, p.305.

Vick, D.W. 2004. Interdisciplinarity and the discipline of law. Journal of Law and Society. 31(2), pp.163–193.

Walker, D. M. 1992. The Scottish legal system: an introduction to the study of Scots law. 8th ed. Edinburgh: W. Green.

Wingate, U. and Tribble, C. 2012. The best of both worlds? Towards an English for academic purposes/academic literacies writing pedagogy. Studies in Higher Education. 37(4), pp.481–495.

APPENDIX A EXTRACT OF QUESTIONNAIRE USED FOR STAGE 1 TEACHER SURVEY

- What would you consider to be your main discipline(s) or specialism(s)?

- What do you teach at college/university?

- EAP general

- ESAP (English for Specific Academic Purposes e.g. English for Management students)

- Other

Guidance for completing the survey:

The remainder of the survey relates to your approaches and attitudes to teaching reading to adults in university or college. All questions have in mind B2+ English language level students

Subject specific reading methods, strategies, approaches

Select 0= don't know n/a = not applicable 1 strongly disagree 2 3 4 5 6 7 strongly agree

- a. There are specific strategies useful for reading in some subjects, fields, or disciplines i.e. they are not generic strategies.

- b. Any differences in strategy use between disciplines, fields, or subjects is minimal or insignificant

- c. Differences in the way experts read in some subjects, fields, or disciplines should be taught by subject teachers

- d. Differences in the way experts read in some subjects, fields, or disciplines should be taught by EAP teachers

Space for additional comments

Question 5: How influential are the following on your attitudes or approaches?

1 not an influence 2 3 4 5 6 7 very strong influence

- your own experiences as a student at undergraduate

- your own experiences as a student at post-graduate

- your own experiences as a reader recently

- EAP course book approaches

- ideas from literature on education

- ideas from literature on linguistics

APPENDIX B EXTRACT FROM STAGE 2 LOG/DIARY