Evaluation of the cultural content in Arabic textbooks

Sara Al Tubuly

Arabic Language and Islamic Studies Department, Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education

ABSTRACT

Textbooks are one of the most important tools used by teachers and educators in teaching foreign languages. Therefore, considerable attention should be paid to how cultural elements can be integrated into textbooks that are used in classrooms (Lewicka and Waszau, 2017). The criteria used by researchers are varied, but there is agreement on some of them. This study evaluates the cultural content and its depth in some Arabic textbooks using a unified set of criteria. It aims to determine to what extent the content of these textbooks reflect Arab culture, and what patterns (such as pictures, maps, music, literature, adverts, TV programmes, games, videos, biographies, literature, jokes, etc.) are included to represent the culture element (Abbaspour et al., 2012).

This study compares and examines four Arabic textbooks by two publishing markets, both within and outside of the Arab world. The finding of the evaluation shows that the textbooks have a cultural and regional impact on the learning process, but the textbooks lack the elements of deep culture that can support students in obtaining intercultural communicative competence (Byram, 1997; Wagner and Byram, 2015). Moreover, non-verbal communication elements which play a role in teaching cultures and their interconnection with the language learning process are not fully covered. Moreover, the textbooks do not tackle issues such as stereotypes and do not reflect perceived positive and negative aspects of the culture.

KEYWORDS: Arabic, textbooks, surface culture, deep culture, cultural competence

INTRODUCTION

Textbooks are widely used by language teachers as one of the most essential means to develop learners’ competence in acquiring languages. Some language textbooks focus on the four core skills (speaking, writing, reading and listening) alongside vocabulary and grammar, while other textbooks are skill specific, where the focus is on certain skills only. Combining two skills together or advancing one skill through the rest are also pedagogically acceptable methods. Nowadays, teaching foreign languages goes beyond teaching the four skills with vocabulary and grammatical structure. Along with these skills, cultural aspects related to the language taught should be integrated in a sophisticated way within the textbooks to raise learners’ awareness and increase their knowledge (Tseng, 2002; Lewicka and Waszau, 2017).

Cultural aspects can be reflected in how people deal, interact and behave overtly and covertly, including their preferences, attitudes, manners, values, traditions and beliefs. Verbal and non-verbal communication is affected by cultural aspects such as social status, religion, time concept, social group and principles. Cultural aspects can also be represented in the food eaten by certain groups, clothing styles and to what extent the body is covered, sports and activities preferred and various forms of arts. Learning and communicating sufficiently in a foreign language cannot be accomplished without obtaining cultural competence, which requires an awareness of and an ability to understand the ways a certain society or group feels and acts and to respect and accept the cultural and linguistic diversity, which includes being able to use the language in a situated context. In fact, this argument extends to include not only the surface culture of the target language but also the deep culture and its dimensions in the development of cultural competence (Henkil, 2001).

Arabic culture, like other cultures, is diverse, and these cultural deviations are varied, depending on geographical, linguistic and individual factors, which is further complicated by the fact that each Arabic-speaking country has a varying dialect, and each dialect tends to be correlated with a cultural structure that is common among Arabs but distinctive to its particular regions. This means we cannot generalise that all Arabs share exactly the same culture or follow the exact same sociocultural customs. In fact, this diversity is not limited to a region or dialect. Within the region, culture can also be diverse among communities that share similar values, expectations, assumptions and ways of communication due to social class, professions, education, etc. Moreover, Arab culture, like other cultures, has been exposed to changes over time, generational differences and other economic and political factors. In this respect, textbooks should also reflect the deep and complex aspects of culture.

Since the 1980s, Al-Batal (1988) urged that culture must be at the heart of the curriculum by understanding the ways in which one can mix culture with other skills in teaching and learning Arabic (Suleiman, 1993; Ryding, 2013). This stresses that culture is an essential component of learning languages and that it is considered as a “fifth skill” alongside reading, writing, speaking and listening. The connection between language and culture is important and strong, as it supports language learners in being proficient in communicating in the target language (Nault, 2006). Brown (2007) also supports that language and culture are highly connected, and this should be brought to light not just by teaching the “values, customs and way of thinking” and not solely the language. The view is that the teaching of the language itself must be accompanied by the culture of the language learned; otherwise, communicating effectively in the target language risks the speaker misperceiving conversations with native speakers (Tseng, 2002; Kramsch, 1993; 2003; Saluveer, 2004).

LITERATURE REVIEW

The significance of integrating culture in language classes and textbooks has gradually become known to teachers and educators. However, integrating culture systematically into language textbooks is challenging. Brown (2000), among others, discussed the relationship between culture and language as though they are two faces of the same coin. Culture and language are shared aspects of communication that are both needed to interact sufficiently with individuals and groups. Language carries linguistic features, while culture carries sociological and behavioural features. This relationship necessitates the idea that learning a foreign language requires learning the culture driving it. The whole process requires careful consideration of how teaching a foreign culture can be embedded in foreign language pedagogy.

Culture within foreign language pedagogy is defined as “patterns of behaviours” by Lado (1957), but Robinson (1988) explains culture in language teaching as “interpretation of the behaviours”. According to Brown (2007), culture entails the tools, ideas, values, behaviours, attitudes and beliefs that distinguish a group of people at a certain time. There are various ways of looking at culture in language teaching. Brooke (1964) was the first to introduce the concept of “capital C” culture, or tangible culture, which is represented in art, literature, music, food, holidays, tourist sites, flags, traditional clothing, etc. On the other hand, “small c” culture is represented in forms of behaviours, attitudes, personal space, concepts of time, approaches to marriage, attitude towards age, etc., and it focusses on interactions in everyday life and in real social settings. It underlines the complex sociocultural interactions in society. This concept of culture develops to mirror that of surface culture versus deep culture (Kramsch, 2013). In an attempt to map small c and capital C culture with surface and deep culture, it is revealed that capital C culture resembles surface culture while small c culture resembles deep culture. The surface culture is easily recognised and distinguished, as it includes physical appearance, tangible characteristics and simple social norms, while deep culture may not be easily recognised unless the individual is exposed to the culture by living in the target culture or by learning about their expectations, attitudes, values, etc. The learners cannot acquire a complete cultural competence of the target language without a true understanding of both levels of culture, including a sensitivity to and awareness of certain situations. A lack of knowledge of deep culture can lead to misunderstandings and misperceptions during communication (Hinkel, 2001; Rodríguez, 2015; Tomalin and Stempleski, 2003; Tudor, 2001).

Hardly (2001) urges us to consider that culture in foreign language pedagogy should not only be limited to observing culture and its aspects but should enable learners to perceive and analyse culture, and this denotes a shift among researchers toward focusing on deep culture as well as surface culture. Risager (2007) promotes incorporating culture into foreign language teaching and including cultural aspects into the curriculum. However, language educators face a challenge in both what and how language-culture curriculum and material should be designed and developed and how the target language and native culture are integrated, especially if the native culture is not limited to one region or language variety and the learners are from different backgrounds. It is argued that intercultural competence is essential in this case for communication purposes.

Byram (1997) proposed a model for intercultural competence in language learning and teaching. It contains four dimensions: language learning, language awareness, cultural awareness and cultural experience. The model starts with learning the language skills in context, then understanding the relationship between language and culture to raise the learners’ awareness of using the language properly in situated contexts. Cultural awareness is a core dimension in the model, as it focuses on how learners develop the ability to understand the target language and its relation to the native culture. This leads to intercultural competence in language learning, and the cultural experience dimension implies that learners obtain intercultural awareness through direct contact with the culture. These dimensions are connected, and the objective of learning and integrating a foreign culture into language teaching materials is to develop the learners’ cultural knowledge and competence rather than just to encourage the learners to copy native speakers’ socialisation patterns (Byram, 1997; Risager, 2007).

Byram etal. (2001), Sercu (2002) and Corbett (2007) argue that the process of learning should not be just passing foreign culture on to learners. The process should involve understanding and acknowledging the difference between knowing and obtaining information about cultures and the ability to compare differences and similarities across cultures with tolerance and appreciation. The latter involves a positive attitude towards learning about other cultures and developing the ability to interact effectively and communicate confidently across cultures. Therefore, curriculums and textbooks should guide students through the process and enable the learners to distinguish between cultural and personal behaviours. Therefore, the goal is to move from communicative competence to an intercultural communicative competence approach. According to Byram etal. (2001), the main components of intercultural communicative competence are represented in the general knowledge about target culture, skills of how to compare, understand and interpret cultures and obtaining a positive attitude towards foreign cultures.

Some researchers agreed on certain criteria to evaluate the cultural content in textbooks, materials and curriculum, but they varied on others. For example, Kilickaya (2004), Reimann (2009) and Byram etal. (2001) agreed on critically handling serotypes and supporting students to reach their own interpretations. Kilickaya (2004) and Reimann (2009) argued that textbooks should engage learners’ own culture with the target language, which implies a variety of cultures, and emphasised that the textbook should include instructions about how cultural elements will be introduced, providing that the reality of the culture will be included and any authors’ views will be avoided by using stimulating materials rather than a holistic approach, where cultural content will be transferred as a source of information only. Whereas, Sercu (2002) emphasised that negative and problematic aspects should be incorporated and that cultural content should be included in the textbook rather than presented in separate sections or attached at the end. Textbooks should ensure that their content deal with deep culture, which reflects values, ideas, attitudes, mentalities and beliefs, including any aspects related to gender prominence and positions in society (Sercu, 2002).

Among all of the criteria for evaluating the cultural content in textbooks (Reimann, 2009; Kilickaya, 2004; Sercu, 1998), Byram’s criteria of cultural content in textbooks and model of intercultural communicative competence (1997; 2001; Wagner and Byram, 2015) emphasised the fact that culture should have more impact on language teaching and learning by not being limited to the four Fs—food, folklore, fair and facts—and include other cultural elements, such as (1) social groups, (2) social interaction, (3) behaviours and beliefs, (4) political situations, (5) life cycles, (6) historical and geographical aspects, (7) cultural heritage and (8) identity and stereotypes. These criteria are comprehensive, although non-verbal communication and conversational patterns in different social situations are not included. However, one can argue that non-verbal communication can be listed under social interaction. Rababah and Al-Rababah (2013) developed criteria for evaluating textbooks used for teaching Arabic to non-Arabic speakers, based on a survey conducted among a spectrum of teachers, tutors and lecturers of Arabic worldwide. One of the criteria was that the culture of the learners and of the language taught must be considered throughout the textbook. Arifin (2012) looked at the cultural content of an Arabic textbook and found references to social interaction, social identity, behaviours and beliefs, cultural heritage and stereotypes, among others. The textbook adopted writing and pictures approach to embed the cultural element into the textbook. Lewicka and Waszau (2017) examined and compared the cultural content in Arabic textbooks that are taught in Polish, French and American universities and found that the textbook used in American universities developed these aspects in more comprehensive ways, allowing for the development of surface cultural competence along with language competence.

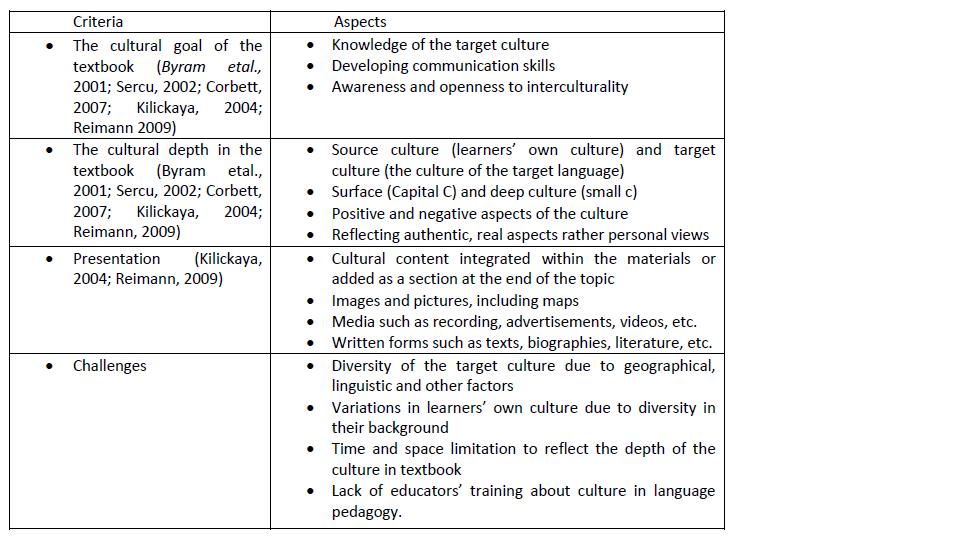

Based on the abovementioned findings, the criteria of cultural evaluation of textbooks vary, and this makes the task complex. However, the researchers agreed on the main elements that can be considered as global trends in cultural evaluation which is summarised in Table 1: language textbooks must have a clear provision in what the cultural goal of the textbook is, the depth of the cultural content is and how culture can be presented in textbooks. However, this does not eliminate the challenges that occur with integrating culture into textbooks and the way in which the materials may be exploited in the class.

Table 1: Summary of cultural criteria

RATIONALE OF THE STUDY

Despite the growth of Arabic language teaching and learning worldwide, an insufficient number of studies on the evaluation of the cultural content in Arabic textbooks have been conducted. Therefore, there is a particular requirement for an objective evaluation to find the extent to which the content of these textbooks reflect Arab culture and society, the tools and patterns included to represent the cultural elements or aspects (Abbaspour et al., 2012) and whether the content of the textbooks match the global trends mentioned previously in teaching foreign languages. The study also examines how these textbooks support or represent intercultural elements (Risager, 1998) during the learning process and whether the cultural aspects of non-verbal communications are being covered.

PROCEDURES

The analysis of the four Arabic language textbooks selected for this study will provide an overview of the depth of the cultural content and patterns used to represent culture. These four books are produced by international publishing houses. Book 1: first level and Book 1: second level are used widely by universities in the UK and the USA. Book 2: first level and Book 2: second level are used in Arabic countries. Following Rodríguez’s (2015) method, the names of the books will not be included in this article, as the aim is to provide an evaluation of the cultural content without affecting the status of the books; these books provide excellent Arabic language materials.

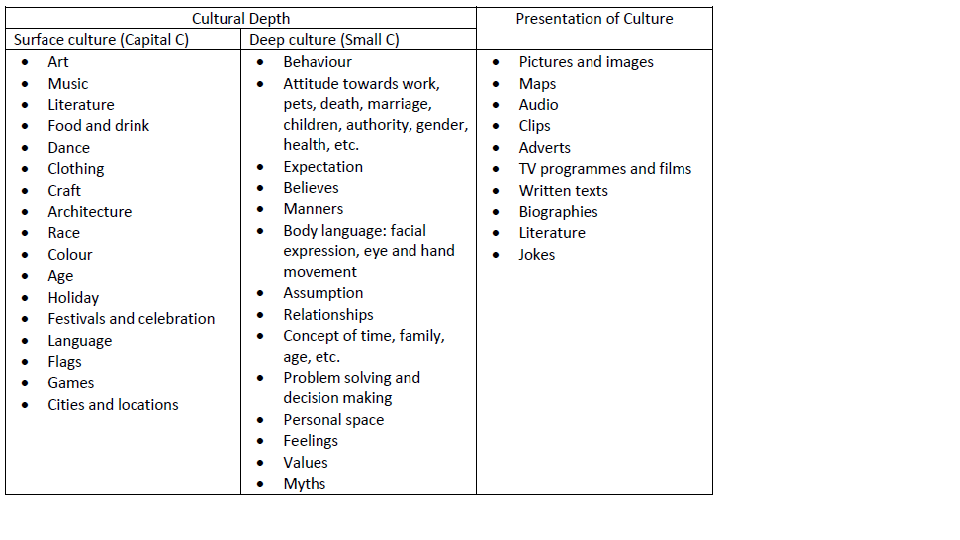

Each page and each chapter of the books were thoroughly examined to identify where and how culture is integrated into the content. Any cultural element found in the books was classified under two main categories, reflecting either surface or deep culture. However, it was not a straightforward task. Following Hall (1976) and other researchers, such as Reimann (2009), Kilickaya (2004), Sercu (1998), Byram (1989; 1993) and Wagner and Byram (2015) and to ensure the reliability of the criteria used, classification of what can be considered deep culture and what can be considered surface culture is listed below in Table 2. Within each level, the tools and patterns adopted by the textbooks to incorporate and represent culture were also identified.

Table 2: Classification of surface and deep culture

Table 2: Classification of surface and deep culture

In order to determine statistically the cultural elements found in the books and what was classified under surface or deep culture, a score was created for each potential pattern or method of representation. For example; one was given for maps, two for images and pictures, three for music, four for literature, etc. For each pattern, another column was created in the data view to determine if it reflects surface or deep culture. So, following the classifications in Table 2, one was given if the pattern reflects surface culture, and two was given if the pattern reflects deep culture. All instances were transformed into scores and entered into the SPSS software (Larson-Hall, 2010; Scholfield, 2011). Descriptive data such as frequencies and percentages were collected. SPSS data were used to make graphs and pie charts to show concrete results and information.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Book 1: first level

Linguistically, Book 1: first level is well structured and comprehensive. It covers the core skills, including grammar and vocabulary, with an authentic approach, and it is accompanied by two CDs and a wide range of online resources. The book covers a variety of themes such as greetings, family relations, jobs, polite requests, describing things and places, countries and people, shopping, food, weather, trips, daily routines, likes and dislikes, education and business. The alphabet is introduced at the beginning in a sophisticated way, by arranging the letters into six groups within the first six chapters. Along with these letters, vocabulary and simple phrases and sentences are introduced.

An examination of the introduction of the book reveals that there is no clear goal or guide on how to use the cultural information or on how to deploy the cultural aspects to raise learners’ deep cultural awareness. On a positive note, cultural elements are embedded in the textbook, and they are not separated or split into sections. Moreover, the book heavily depends on the use of photos that put the Arabic language into its cultural context from the beginning. However, the photos mainly reveal aspects of surface culture. Some photos show that Arabs are famous for their hospitality. Other photos include old Arabic cities and streets, traditional clothing, houses and food and maps of some of the Arabic countries from the Middle East, as well as museums, royal palaces, nature, traditional markets and restaurants. Some cultural content is also reflected in the written form. Various Arabic proper nouns, names of countries, nationalities and names of traditional dishes are included in the textbook. Furthermore, videos of Arab speakers are incorporated into the content of the textbook where the background, context and features of the speakers reflect Arabic culture and nature. Furthermore, there is a slight reference to intercultural elements in a limited number of pictures, depicting some of the wonders of the world through the use of proper nouns and mentioning Western features.

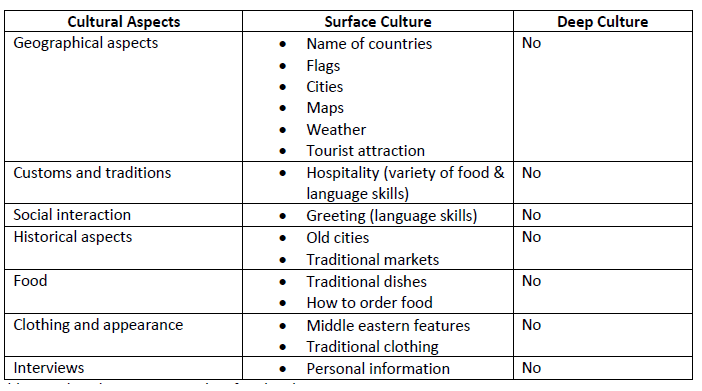

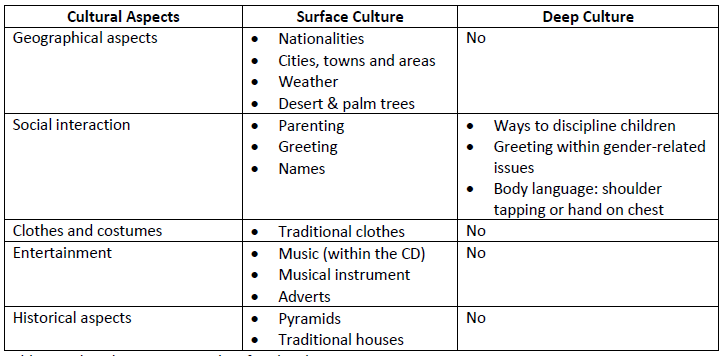

Table 3 below shows the cultural aspects found in Book 1: first level and their classification in terms of deep or surface culture. It seems that none of the aspects mentioned above could reach or reflect deep culture. This can be attributed to the beginner level of the book. However, the book touched on cultural aspects such as hospitality and greetings but only at the surface level that includes language expressions which are used in greetings, such as مرحباً ، أهلاً و سهلا، تشرفنا، مساء الخير، مساء النور، صباح الخير، صباح النور، كيف حالك، مع السلامة، إلى اللقاء،. Hospitality was represented in some vocabulary and various traditional dishes, such as تفضل، تفضلي، كسكسي، فلافل، مهلبية، كشري، كباب، الله يسلمك، مائدة. Additionally, a tip is added to the text in English emphasising that Arab culture is known for hospitality and generosity. These two cultural aspects are directly connected to the language as a means of communication at the surface level because there was no reference to the concepts of friendships, attitudes and manners towards guests or social interaction based on gender-related issues.

Table 3: Cultural aspects in Book 1: first level

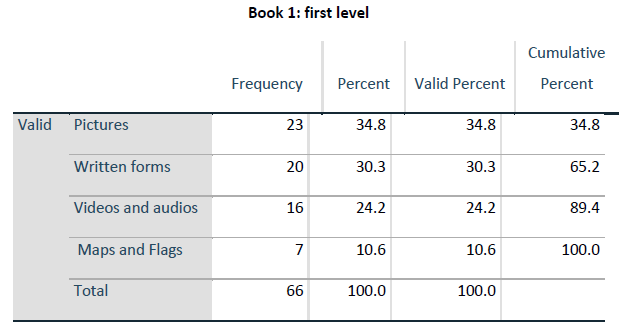

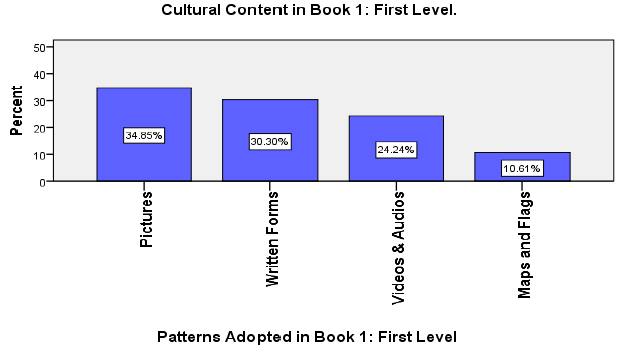

The cultural content in the textbook shed light on positive aspects without trying to impose the authors’ opinions and views in an attempt to only transfer cultural information to learners. However, the content of the book does not develop the learners’ deep awareness of the target language’s cultural aspects. There are four patterns used in Book 1: first level to integrate culture. This textbook mainly relies on pictures and photos, as mentioned previously, to reveal some aspects of culture, followed by written texts that contain cultural references about various topics and themes. The number of instances in which cultural elements are referenced in the video and audio is higher than those in the maps or flags, as shown in Figure 1 below. Table 4 reflects the frequency at which these cultural instances occurred.

Table 4: Frequency of cultural instances

Figure 1: Book 1: first level

Book 1: second level

With regard to Book 1: second Level, it is no different from the first level in terms of language structure. It includes core skills as well as grammar and vocabulary in an authentic, engaging and attractive style, and it is accompanied by CDs and a wide range of online resources. The book covers a range of themes such as speaking about oneself and others by describing personalities and talking about childhoods. Book 1: second level moves from personal information to professional issues. This includes information about home and housework, how to rent a house, daily routines, searching for jobs and writing CVs. The book has celebratory themes, starting with sports and leisure, hobbies, free time, preferences, travel and tourism, festivals and transportation and ending with food and cooking, booking tables in restaurants, wedding parties, colours, fashion shows and buying clothes. The themes become more abstract in the final part of the book and introduce issues such as media and broadcasting, news and speech, advice and complaints, environment and weather, happiness and health and arts and cinema.

Similar to its first level, the cultural content in Book 1: second level is introduced through pictures showing different aspects and features of Arab culture such as traditional buildings, old and modern cities and famous dishes. The cultural content is also incorporated in both written text and audio. In contrast to Book 1: first level, this textbook contains Arabic proverbs and poetry, biographies about famous writers and famous singers and several adverts for products, jobs and houses for rent, reflecting some cultural aspects. There is no strong presence of literature at this level, but it is not absent. One of the strong cultural presences in this textbook is a section at the end of each chapter that includes information about an Arabic country. These sections are accompanied by maps, and each map includes the names of the capital and the many other cities, seas, rivers, etc. They include audio samples of authentic regional dialects. Furthermore, the two main festivals, Ramadan and Al-Hajj, are included in the textbook with a text explaining some details about the traditions and customs involved. Music, dance and celebrity make limited appearances in the textbook.

Unlike Book 1: first level, there is no clear reference to intercultural elements that reflects the source culture, but greeting terms are developed with regard to the book’s level to include intermediate expressions such asأسعد الله صباحك بكل خير، عيد مبارك/ مبروك، السلام عليكم و رحمة الله و بركاته، كل عام و أنتم بخير، الحمدلله على السلامة. In Book 1: second level, two exercises introduce learners to deep culture, as shown in Table 5 below. One of the exercises involves reading a piece of news about the Tamazight Language and how it was introduced in schools for the first time in Algeria, “للمرة الأولى، تعليم الأمازيغيةبالمدارس الجزائرية”. The learners thus have the opportunity to obtain knowledge about multiculturalism within Arabic culture, linguistic plurality and populations and ethnic pluralism with the increased awareness that there is another language spoken in parts of North Africa alongside the Arabic language. One more reading of the text shows that women should wear modest clothes in the Arab world due to religious and cultural reasons and as a sign of respect, “ملابس النساء أيضاً محتشمة و فضفاضة و تغطي كل الجسم”. However, these two cultural aspects mentioned above can have some implications. Therefore, there should be a reference to the diversity of Arabic culture with regard to outfits and costumes, and there should be more discussion about the conception of including Tamazight language in the curriculum, taking into consideration the various views of different social groups. Apart from these two points, the rest of the cultural content represent surface culture and refers to mono-cultural aspects.

Despite the inclusion of various written texts such as biographies, poetry and proverbs, the content of these texts do not go beyond surface culture and language terminology (as shown in Table 5). For example, the content of the biographies do not reflect the status or value of individuals in the society or the attitude of the public to them. The texts include information about their life, their place and date of birth, death, etc. using vocabulary such as ولد في أمضى، حصل على، نشر ، بدأ، انتقل، درس، مات، حضر،. There was a mention that the singer “Omm Kalthoum” is also called the “star of the east” (كوكب الشرق), but no further explanation is given of how Arabs feel about her songs or her music style. Moreover, the book has transferred information to the learners about the month of Ramadan (شهر رمضان) and the Hajj (الحج), the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, as main festivals in the Arab world, but there was no attempt to reach deep culture by explaining that not all Arabs practice or celebrate the Eids. Also, the content does not contain discussion about the manners and expectations related to the Eids.

With respect to Arabic dialects that are included at the end of the chapters, according to the surface and deep culture classification proposed in Table 2, the inclusion of Arabic dialects does not reflect deep cultural aspects. However, one can argue that introducing learners to different dialects with different accents can raise learners’ intercultural awareness of the Arabic diglossia (i.e. sociolinguistic variation in the Arab world) and its implications, enabling them to recognise the different registries of the language, and it is also a preparation to avoid the chance of facing a future culture shock that may be experienced by learners during their travel abroad in the Arab world.

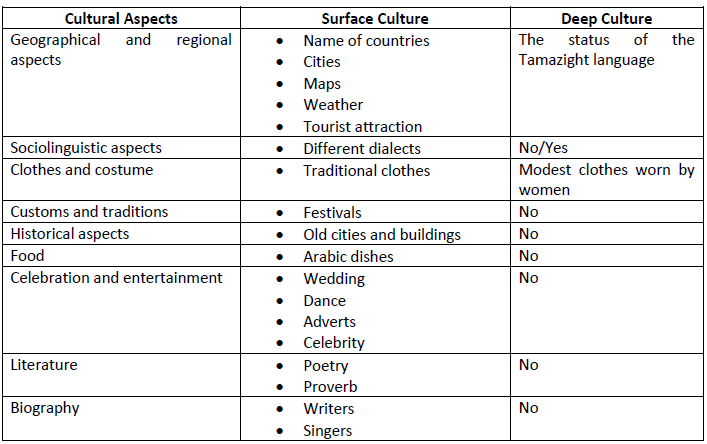

Table 5: Cultural aspects in Book 1: second level

Table 6: Frequency of cultural instances

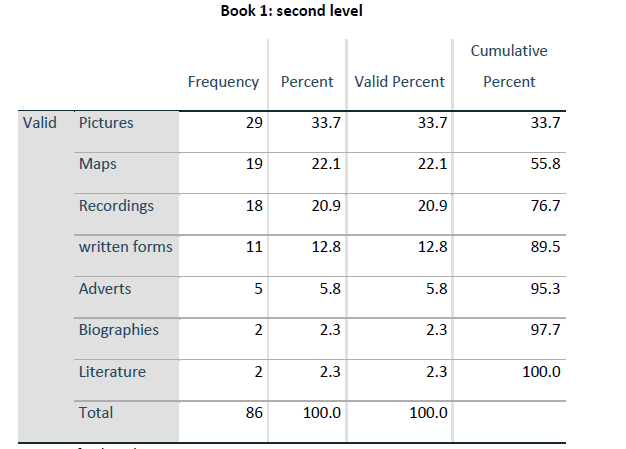

More patterns are adapted in Book 1: second level in order to further integrate surface culture. The most frequent methods used at this level are pictures, maps and recordings, while the least frequent means are literature and biographies. There are limited instances of adverts with cultural content, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Book 1: second level

Book 2: first level

The content of Book 2: first level is mainly in Arabic at the beginner level with no use of English. The book also opens from the right side. The letters are divided into five groups, according to the alphabetical order but not in terms of their common features, along with some vocabulary and basic phrases. It is composed of 10 chapters, and it covers the core skills, including grammar and vocabulary, with sections to introduce students to the use of language in naturalistic settings. The linguistic content of the book is enriched with recordings found in CDs and online resources. Similar to other language books, this book starts with themes such as greetings, introducing oneself and getting to know others, their nationalities and personal information. It also includes some courtesy, apology, politeness and thanking phrases along with titles to address people, such as آسف، لا مشكلة، شكراً جزيلاً، بكل سرور، يا آنسة، يا أستاذ، يا سيد. However, the book does not present assumptions, expectations or behaviours associated with using titles and addressing colleagues, lecturers, strangers within the workplace, etc. These phrases and titles are not highlighted in light of the variations between societies in the West and the Arab world.

Through the examination of the cultural content in the book, it seems that the focus on cultural content is highly limited. The book does not include guidance or clear objectives on how cultural elements should be handled, and it does not target the learners’ own culture, except in rare occasions when some foreign names are given to some characters in the book. The book also focusses on numbers in Arabic by introducing themes such as dates, phone numbers, time and prices. Book 2: first level familiarises students with description skills by introducing topics such as clothes, colours, places and directions. It ends with teaching students how to talk about daily routines, family members, weather conditions and temperature. Patterns such as pictures, music, recordings and some adverts are embedded in the textbook. The pictures used in this book reveal cultural aspects related to clothes and costumes, traditional houses and historical architecture. Some pictures illustrate the deserts found in some Arabic regions showing camels and palm trees in several locations. Eastern musical instruments, such as the oud, are also found in the pictures.

Similar to other language books at this level, flags, nationalities and geographical aspects have a strong presence. Contrary to previous books, cultural aspects such as food, famous figures or festival have no presence at this level. However, the book includes some themes typical of surface culture, but they are informed by deeper cultural assumptions, expectations and behaviours. For example, the book embraces some deep meanings related to social interaction solely through pictures. It shows ways to discipline children that may be acceptable in a particular society, and it refers to some non-verbal communications when greeting people such as taps on shoulders or taps on the chest. Thus, the body language accompanying verbal expressions seems to be present in some pictures and images. It can be considered as one of the merits of this book, as non-verbal communication is significant in light of the potential cultural dissimilarities between societies.

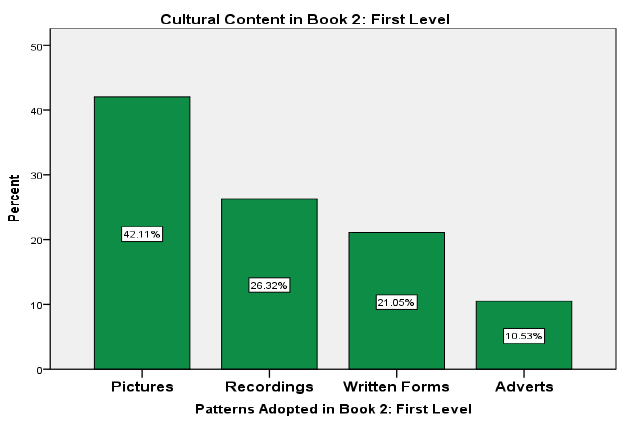

Interestingly, all pictures used to show greetings are limited to greetings within the same gender. This might be accidental, as there are no clearly written texts explaining these behaviours, assumptions or sociocultural norms. It can also be noticed that various and different Arabic names are used for characters or people mentioned in each lesson and dialogue, which has a positive impact on the learners’ cultural knowledge with regard to the distinction between feminine and masculine Arabic proper nouns, but this aspect does not feed into deep culture. In other cases, intercultural content is introduced in the form of exercises. For example, in an exercise about “Nisba adjectives” and nationalities such as بريطانيّ، إيطاليّ, the task refers to rugs as “Iranian”, fashion items as “French” and electronic equipment as “Chinese” or “Korean”, symbolising the reputation of each country for exporting such items to the world market. However, apart from the three deep cultural aspects mentioned above, all other cultural aspects do not go beyond the surface culture, as shown in Table 7 below.

Table 7: Cultural aspects in Book 2: first level

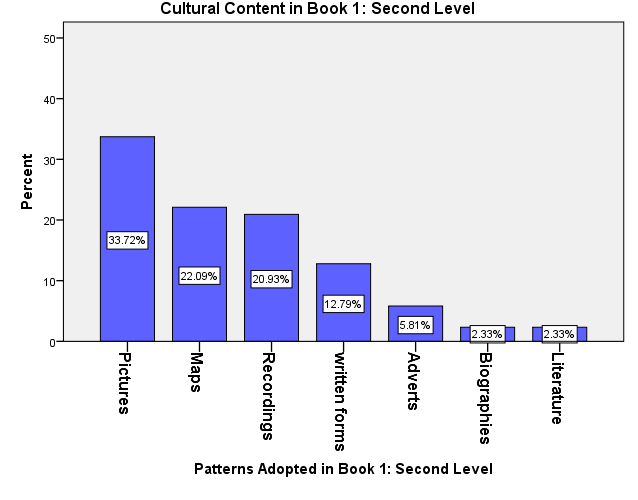

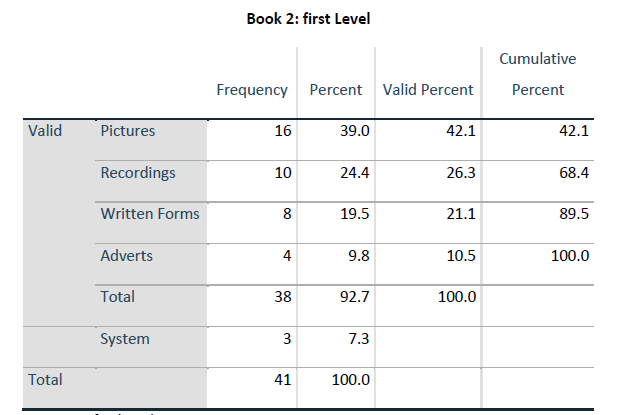

Once again, it seems that pictures are the primary source in Arabic textbooks to show and reveal cultural elements, evident from it being the highest column in Figure 3 below. No large differences between the recordings and the written texts were noticed. However, it seems that a few written texts have been deployed to reveal cultural aspects, as shown below. These appear in terms of area names, street names, addresses, shops names, etc. This can be attributed to the level of the book itself. The pattern least adopted to reveal culture is adverts, which scarcely appear in the book.

Table 8: Frequency of cultural instances

Figure 3: Book 2: first level

Book 2: second level

Book 2: second level is a higher level textbook with broad topics that develop linguistic and communicative skills. The book is composed of eight chapters. It teaches students how to describe people, objects, occasions and places. It also teaches them how to talk about daily routines and future plans. It develops their skills to read and understand short stories, articles about prominent figures, job advertisements and news through themes such as successful relations, abilities and orders, events from the past, trips and activities. Similar to previous books, this book covers the four core skills, including vocabulary and grammar, and it puts the language into function by using it in real-life situations.

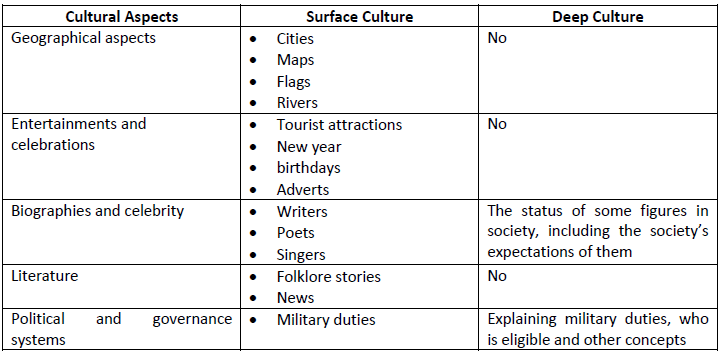

In Book 2: second level, the cultural content is mainly found in pictures and biographies. A range of famous figures and prominent celebrities from the Arab world and further abroad are included in the book, which reflects an intercultural approach because it relies on the idea that culture can be best learned by comparing, engaging and including the target culture and the learners’ own culture, which might enable learners to function as facilitators between the two cultures (Risager, 1998). In addition, folklore stories, which are part of Arabic literature, are found such as “Juha” (جحا), introducing learners to the genre of these stories and the sense of humour these types of stories have. The argument behind this point is that deep culture can be informed by surface culture in this case. To achieve this goal, there should be clear guidance and instruction for teachers who will be using the book to expand on the task in order to reach the deep culture and avoid the risk of misusing the text in the class. Also, the reading texts are embedded with names of famous Arabic streets, cities, areas, rivers and buildings. The book also includes the most famous Arabic tourist attractions and holiday resorts. News and job adverts are included in the book, and they reflect some sociocultural norms. Likewise, the inclusion of celebrations such as birthdays and New Year introduces students to lifestyles and cultural customs. Infrequently, maps and flags are used in the book to incorporate cultures.

There is a strong presence in Book 2: second level of biographies of famous and prominent figures and celebrities with a richness in vocabulary such as نالت، تخصصت، أسست، شاركت، ألفت، تتلمذ، مطرب، لقب، المركز. Dissimilar to Book 1: second level, some biographies do not only show who the individuals are and what they do but also include their social status, the perception of Arab society towards them and their value in the community. Occasionally, there are footnotes regarding the figures that encourage the learners to carry out research to learn more about them and any cultural matters connected to them. There was no focus on historical aspects in this book, but some geographical and political aspects are noted in the texts and pictures. The text explains the concept of military duty in the Arab world and how it is a compulsory responsibility to certain groups of that society. It also makes learners aware of the cultural dissimilarity between the Arab world and the West towards this duty and of the attitude and feeling of the Arab world towards this national service. Table 9 below shows more details.

Table 9: Cultural aspects in Book 2: second level

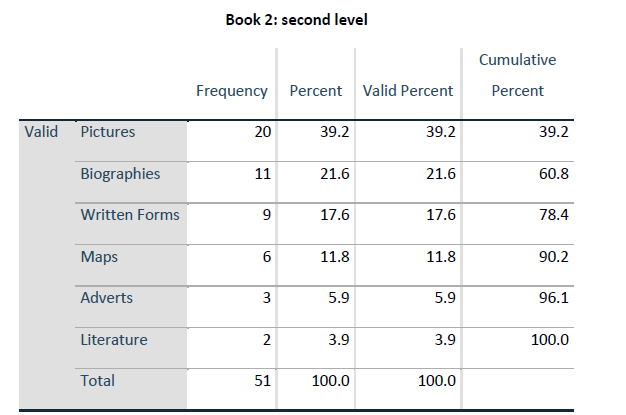

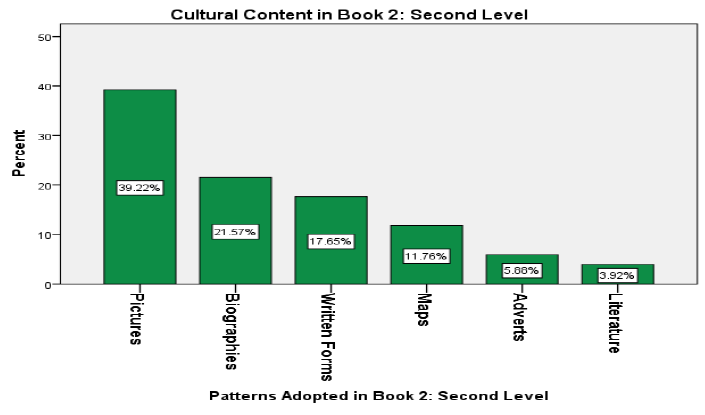

Unlike previous books, biographies in Book 2: second level are the second most frequently occurring pattern, following pictures. There are more instances of cultural references in written texts and maps than in adverts and literature.

Table 10: Frequency of cultural instances

Figure 4: Book 2: second level

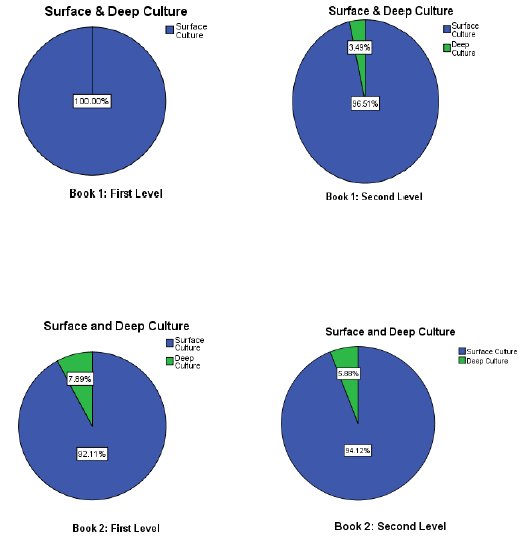

The four books that were examined display elements and aspects of surface culture as shown in the findings. However, they lack the elements of deep culture which can support students in obtaining intercultural communicative competence (Byram, 1997; Wagner and Byram, 2015). Book 1: second level, Book 2: first level and Book 2: second level have limited elements of deep culture. Book 1: first level totally lacks deep culture, as seen in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Surface and deep culture

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The textbooks examined include comprehensive coverage of linguistic and communicative skills. They also contain information on various surface cultures. However, some deep culture content has been introduced in the books through the rear door, but it was not clearly acknowledged. Therefore, this evaluation should encourage teachers to introduce cultural elements openly in the class and encourage the authors of textbooks to state their cultural goals and objectives freely in the guidance and preface sections of the textbooks. Moreover, textbooks can benefit from cultural tips to raise students’ cultural competence without fearing that these tips may lead to stereotyping some cultural elements. Culture should not be fed to learners but rather introduced to them with its perceived positive and negative sides, and learners should be encouraged to compare, understand and interpret cultures to develop their own attitude towards such foreign cultures (Byram etal., 2001). Therefore, teachers and textbook authors should critically handle serotypes and support learners in reaching their own interpretation (Kilickaya, 2004; Reimann, 2009) as mentioned previously.

Some of what is presented as surface culture can lead to or feed deep culture. For example, within the greetings sections, there are non-verbal communications features that should be incorporated into greeting terms in the textbooks in a more comprehensive way, such as taps on shoulders, hands on chest, rubbing noses by Bedouins, exchanging hugs and kisses on cheeks within members of the same gender. Dealing with gender in greeting can be complex and may cause misunderstandings if learners are not aware of the depth of this cultural element. Another example of deep culture that is informed by surface culture is related to food. Three of the books display different traditional dishes that reflect Arabs’ surface culture, but none of the books explain that there are types of dishes eaten by hand and require sitting on the ground in certain regions of the Arab world. There are also other issues that are not incorporated into these books. For example, it is preferable to eat with the right hand, and splitting bills in restaurants among friends, family members or colleagues is not the norm in the Middle East. Moreover, within shopping themes, it is ideal to raise learners’ cultural awareness of bargaining in traditional markets, as it is common in the Middle East. One of the gaps that should be filled is the introduction of non-verbal communications, including body and facial expressions. Common stereotypes are totally absent, such as Arabs always being late, Arab women being oppressed or all Arabs being Muslim. However, these topics develop debate skills to prove whether they are true or false. Other concepts related to cultural dimensions, such as time flexibility, attitudes towards family, elderly people, age and marriage, approaches to religion, decision making, raising children and relations with animals and pets should be paid more attention in textbooks, and discussion should be held in the classroom at an intercultural level, where the source culture (learners’ own culture) and target culture (the culture of the target language) are both engaged.

It is essential to design cultural materials that are based on real-life resources, such as movies, dramas, programmes, documentaries and native speakers’ inputs, reflecting authentic, real aspects rather than the authors’ personal views. This will help students to not only develop a cultural competence but also critical skills that go beyond the culture of the country whose language is being studied to include the culture of the learners as well.

Some major issues with the textbooks analysed are that only a few instances are recorded of deep culture. This means that learners are not fully prepared to live and communicate in the country of the language taught, and they may miss vital tips that allow them to interact successfully without experiencing miscommunications or culture shock. Learners would not be able to communicate confidently without acquiring the cultural aspect along with other skills (Garza, 2016). Deep cultural awareness assists in understanding the differences and similarities between people. This will prepare them to accept differences and consider them as a way to learn about others. When students’ deep culture knowledge and awareness are embedded with a positive attitude, they will value and respect cultural diversity and become more open and willing to accept others. Eventually, critical skills such as evaluating and understanding the customs and traditions of other peoples will develop (Barrett, 2011).

Teaching Arabic as a foreign language needs systematic, in-depth and up-to-date curricula that deploy high standards of teaching and learning to achieve linguistic development as well as cultural competence. Language teachers are also responsible for and have a major role in promoting cultures. They should avoid using textbooks as their only source in the curriculum and aim to fulfill potential gaps left by textbooks. To be able to achieve this goal, factors such as the context in which the language is taught and whether or not the students are in real contact with the culture being studied must be also considered. It is also worth mentioning that challenges and implications facing practitioners due to the diversity of culture within the Arab world, the diversity of the learners’ own cultures in the classroom (particularly if they come from different backgrounds) and the time constraints and space limitations in textbooks and classes can be barriers to reflecting the cultural depth required. Therefore, more training and workshops about how to integrate culture and how to classify deep and surface culture in textbooks are very much needed in Arabic language pedagogy, because learning Arabic, as with any other language, not only requires learning linguistic communication but also requires learning about the cultural wealth associated with the language, whether visible or hidden, negative or positive.

Address for correspondence: s.altubuly@almcollege.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Abbaspour, E., Nia M.R., and Zare’, J. 2012. How to integrate culture in second language education? Journal of Education and Practice. 3(10), pp.20-24.

Al-Batal, M. 1988. Towards cultural proficiency in Arabic. Foreign Language Annals. 21(5), pp.443-453.

Arifin, M.N. 2016. A study of cultural aspects in Arabic textbooks for madrasah ‘aliyah in Baten. Saintifika Islamica: Jurnal Kajian Keislaman. 3(2), pp.131-144.

Barrett, M. 2011. Intercultural Competence. EWC Statement Series. 2, pp.23-27.

Brooks, N. 1964. Language and language learning: theory and practice. New York: Brace & world Inc.

Brown, H. 2002. Principles of language learning and teaching. NY: Longman.

Brown, H. 2007. Teaching by principles. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Byram, M. 1989. Cultural studies in foreign language education. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. 1993. Language and culture learning: the need for integration. In: Byram, M. ed. Germany, its representation in textbooks for teaching German in Great Britain. Frankfurt am Main: Diesterweg, pp.3-16.

Byram, M. 1997. Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M., Nichols, A. & Stevens, D. 2001. Introduction. In: Byram, M., Nichols, A. & Stevens, D. eds. Doing intercultural competence in practice. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Corbett, J. 2003. An intercultural approach to English language teaching. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters LTD.

Garza, T. 2016. Culture. Foreign language teaching methods. [Online]. University of Texas. Available from: https://coerll.utexas.edu/methods/module/culture/

Hall, R. 1976. Beyond culture. NY: Anchor.

Hardly, A. 2001. Teaching language in context. Boston: Mass Heinle & Heinle.

Hinkel, E. 2001. Building awareness and practical skills to facilitate cross-culture communication. In: Celce-Murica, M. ed. Teaching English as a second or foreign language, Boston: Heinle & Heinle, pp. 443-458.

Kilickaya, F. 2004. Guidelines to evaluate cultural content in textbooks. The Internet TESL Journal. 10(12), pp.38-48.

Kramsch, C. 1993. Context and culture in language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kramsch, C. 2003. Teaching language along the cultural faultline. In: Lange, D. and Paige, R. eds. Culture as the core: perspectives on culture in second language learning. Greenwich: Age publishing, pp.19-35.

Kramsch, C. 2013. Culture in foreign language teaching. Iranian Journal of Language Learning Research. 1(1), pp. 57-78.

Lado, R. 1957. How to compare two cultures. In: Lado, R. ed. Linguistics across cultures. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Larson-Hall, J. 2010. A guide to doing statistics in second language research using SPSS. New York: Routledge.

Lewicka, M. and Waszau, A. 2017. Analysis of textbooks for teaching Arabic as a foreign language in terms of the cultural curriculum. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(1), pp.36-44.

Nault, D. 2006. Going global: rethinking culture teaching in ELT contexts. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 19(1), pp.314-328.

Rababah, H.A., and Al-Rababah, I.H. 2013. A criteria for evaluating textbooks used for teaching Arabic to non-Arabic speakers: language teaching methodology. European Journal of Social Sciences. 38(4), pp.453-469.

Reimann, A. 2009. A critical analysis of cultural content in EFL materials. Journal of the Faculty of International Studies, Utsunomiya University. 28(8), pp.85-101.

Risager, K. 1998. Language teaching and the process of European integration. In: Byram, M. and Fleming, M. eds. Language learning in intercultural perspective: approaches through drama and ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.242-254.

Risager, K. 2007. Language and culture pedagogy: from a national to a transnational paradigm. Clevdon: Multilingual Matters.

Robinson, G. 1988. Cross cultural understanding. Hertfordshire: International Ltd.

Rodríguez, L.F.G. 2015. The cultural content in EFL textbooks and what teachers need to do about it. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development. 17(2), pp.167-187.

Ryding, K. 2013. Teaching and learning Arabic as a foreign language: a guide for teachers. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Saluveer, E. 2004. Teaching culture in English classes. Master’s thesis, University of Tartu.

Scholfield, P. 2011. Simple Statistical Approaches to Reliability and Item Analysis. Lecture notes distributed in LG 675 Quantitative Research Methods in Language Study. University of Essex.

Sercu, L. 1998. In-service teacher training and the acquisition of intercultural competence. In: Byram, M. and Fleming, M. eds. Language learning in intercultural perspective: approaches through drama and ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.255-289.

Sercu, L. 2002. Autonomous learning and the acquisition of intercultural communicative competence: some implications for course development language. Culture and Curriculum. 15(1), pp.62-74.

Suleiman, Y. 1993. TAFL and the teaching/learning of culture: theoretical perspectives and an experimental module. Al-‘Arabiyya. 26, pp.61-111.

Tomalin, B. and Stempleski S. 2003. Cultural awareness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tseng, Y. 2002. A lesson in culture. ELT. 56, pp.11-21.

Tudor, I. 2001. The dynamics of the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wagner, M. and Byram, M. 2015. Gaining intercultural communicative competence. The Language Educator. 10(3), pp.28-30.