An IELTS writing course based on the need analysis of Saudi learners

Hira Hanif, King’s Foundation, King’s College London

ABSTRACT

The significance of the IELTS test has recently increased in Saudi Arabia. An increasing number of students seek higher education in foreign universities abroad. These universities necessitate a high level of English language proficiency as an entry requirement. IELTS is widely used by these institutes as their criterion for admission. However, it has been noted that Saudi learners often score the lowest in the world in the writing component (IELTS, 2012). This paper reports on a small-scale study that was conducted to meet the need of this learner community; after conducting a detailed need analysis, this paper proposes an IELTS writing course based on a genre analysis approach.

KEYWORDS: IELTS, writing skills, genre approach

INTRODUCTION

The growth of English language education worldwide has led to an increase in English for specific purposes (ESP). It has been argued that every course should be relevant to the specific group of learners (Long, 2005). However, in Saudi Arabian higher education context there remains a paucity of courses that suit the needs of this learner community. This paper aims to fill this major gap and provides a template approach for course design. The purpose of this paper is to design an English for specific purposes writing course for Saudi Arabian adult learners who want to travel abroad for higher education. The course will prepare these learners for academic studies abroad and will also act as a preparation course for the IELTS exam by equipping them with the necessary skills required to pass the exam. This paper will first discuss the context and rationale for the course. Briefly discussing the relevant literature, it will also highlight the scarcity of such studies in this context. The paper will then discuss the process of need analysis (NA) of these learners. Based on this analysis the syllabus for this course will be proposed and suitability of the course material and textbooks will be discussed.

Context

The significance of the IELTS test has recently increased in Saudi Arabia. In 2005, the King Abdullah Scholarship program (KASP) was launched to establish sustainable human resources in Saudi Arabia by supporting Saudi Arabian learners to study abroad. As a result of this scholarship an increasing number of students now seek higher education in foreign universities abroad. These universities necessitate a high level of English language proficiency as an entry requirement. IELTS is widely used by these institutes as their criterion for admission. In addition, the Saudi students also need adequate level of academic English to succeed in their academic programs in their universities abroad. Consequently, the demand for IELTS preparation courses and English for general academic purposes (EGAP) courses in the kingdom has increased drastically. To meet these demands, all the universities in the kingdom offer a course called the preparatory year program (PYP), which introduces the learners to general academic skills that would help them in their higher education abroad. However, the PYP does not equip the learners with the necessary skills required for their IELTS exam. To meet this need, several private academies have started offering IELTS preparation courses. However, both of these above-mentioned types of courses are based on a model, which Deakin (1997) calls a separated model, and none of these are sufficient on their own in their capacity to meet the needs of these learners.

Rationale

During my appointment as an ESL instructor in PYP programs and in an academy offering IELTS preparation programs, I noted the dissatisfaction of the learners with lessons, methodology, and materials. This was due to the courses’ inability to meet the needs of this particular learner community. Similar dissatisfaction has also been noted by Long (2005). Therefore, I decided to offer an ESP course for Saudi Arabian learners based on Deakin’s (1997) ‘integrated’ model where IELTS preparation will be incorporated into the English for Academic (EAP) course. This course, therefore, aims to meet both academic and IELTS needs of the learners. The course will be called Academic writing for IELTS exam and university studies. The course, as the name implies, will be restricted to writing skills only. The reason for this is that writing is the most immediate need of these learners. Through my experience as an EFL instructor in Saudi Arabia, I was able to deduce generalisable information about the learner needs in my context. It was obvious from my observation and reflection notes that these learners suffer from serious problems with their English writing. This finding was further confirmed by the IELTS score of the learners from this context. According to the test performance report published by IELTS (2012), in 2012 the average band score in the writing component achieved by Saudi Arabian learners was 4.7, which was the lowest among the test takers from forty countries. Similarly, in 2013 these learners achieved the second lowest score in the world in the writing component (i.e. 4.9) (IELTS, 2013). Considering most western universities have a score of at least 6.5 as a minimum entry requirement, a big gap between the present situation and the target situation of Saudi Arabian learners is evident. Several empirical studies also confirm that writing is the most immediate need of these learners and the academic progress of Arab university students is affected due to their language proficiency (Al-Khairy, 2013). Therefore, I would like to approach the test preparation within the broader context of pre-tertiary EAP. The differences between the IELTS writing tasks and the writing required of university students has been analysed by several researchers (Moore & Morton, 2007). This course will not only attempt to meet the immediate needs of the learners but also attempt to familiarise them with pre-tertiary education they will embark on after passing the test.

Literature Review

The concept of ESP developed in different parts of the world in 1960s; soon after other branches emerged including English for science and technology (EST), English for occupational purposes (EOP), English for academic purposes (EAP) etc. (Chazel, 2014). Courses designed for language for specific purposes base their methodology, content, objectives, materials, teaching, and assessment practices on the specific, target language uses based on a set of identified specific needs (Trace et. al., 2015). Designing and proposing language for specific purposes courses based on need analysis of learners has become a common practice around the globe. Some examples include Hillman, (2015), Lee, (2015), Ho (2015) and Oh (2015) who have proposed syllabuses based on need analyses of particular groups of people. Trace et. al. (2015) has presented several other studies that have proposed language for specific purposes courses to meet the specific needs of the learner in different contexts. Some of these include Mandarin for nursing students, Polish for health personnel, developing business Korean curriculum for advanced learners in an American university and Hawaiian for indigenous purposes to sustain Hawaii’s rich culture and language. As the names illustrate, all of these courses were need driven to meet the unique requirements of particular groups of learners. However, in Saudi Arabia, although conducting need analysis is not uncommon for research purposes, such as Khan (2019) and Zughoul & Hussein (1986), specifically designing courses based on these needs is not common. In particular, there has not been any course offered or proposed in Saudi Arabia to meet the needs of this specific group of students who goes abroad for further studies. After taking their IELTS exams in Saudi Arabia, the students usually complete a pre-sessional course in the host country before they start their undergraduate or graduate studies in the host country. The aim of these courses is to prepare international students for higher studies in the UK. The researcher recently had a chance to teach at some of the pre-sessional courses offered in one of the universities in the UK. It was noted that although these courses aim to meet the needs of international students, they are not particularly designed for Saudi Arabian students. It is, therefore, believed that the course proposed in this paper will not only specifically meet the needs of Saudi students, but it will do so in their home country. Economizing the resources, they will also prepare for the IELTS exams at the same time.

Practical considerations

I will be teaching the course face-to-face and it will be held in a rented conference hall in Riyadh. The course will run twice a week on the weekends and will last for 10 weeks. The students will be intermediate to upper intermediate EFL learners who, depending on the number of students enrolled, will be divided into two groups and taught in separate sessions. The course will be restricted to female learners only due to the laws pertaining to gender segregation in the country.

Need analysis

Need Analysis (NA) is an essential step in designing any ESP course. It can be divided in two parts including present situation analysis (PSA) and target situation analysis (TSA). The PSA focuses on the learners’ lacks and TSA focuses on what competencies learners need to have to function in the target situations. It can be inferred from the learners’ enrolment in the course that these learners will have a shared goal of improving their writing and consequently improving their scores in the writing component of the IELTS exam. However, PSA will be required to analyse their cognitive styles, preferred learning strategies and existing knowledge of the language. In Hutchinson and Waters (1987) model, when designing syllabus, attention is also paid to conditions such as speed, time, resources, efficiency etc. The following discussion will show the need analysis stage of this course.

Sources and methods

There is a common consensus among the researchers about the efficacy of using multiple methods in any research (Cowling, 2007). The following sources were, therefore, identified for the PSA and the TSA.

- Learners enrolled in the course.

- IELTS examiners who have experience of marking written IELTS exams of Saudi Arabian learners.

- ESL instructors who have experience of teaching writing skill to these learners in EAP courses.

- Former learners who have taken IELTS exam and have studied abroad in university settings.

- Literature related to the writing deficiencies of Saudi Arabian learners.

Also, it is important to mention that gaining access to the IELTS written exams completed by Saudi Arabian learners would have helped the researcher to gain beneficial insights into the PSA of these learners. However, the researcher was not able to gain access to the Cambridge Learner Corpus that holds the exam scripts of the learners. Only specialists at the Cambridge University Press have access to this corpus.

DATA GATHERING

Participants

The process of data gathering was challenging. The researcher was not working at the time of the research; therefore, gaining access to institutes to interview the instructors or examiners was not possible. Subsequently, an online questionnaire was designed and sent to Saudi Arabian professionals, who had taken the IELTS test and also had an opportunity to study in the universities abroad. Unfortunately, the rate of response of these surveys was significantly low, making it impossible to draw any generalisable conclusion from these findings. The questionnaires were also sent to IELTS examiners and ESL instructors through a professional networking site. Concerning ethical considerations, the respondents of the questionnaires were made aware of the objectives of the research and they voluntarily chose to participate in the study. Anonymity of individuals participating in the need analysis was also ensured. Although an analysis of the data gathered is beyond the scope of this paper, it would be reasonable to say that through the information gathered, the researcher was able to assess the most important writing needs of these learners. Notable limitations in grammar, vocabulary, use of coherence devices, and use of appropriate register were identified as their most immediate needs.

In addition, the learners taking a course also called the ‘target group’ (Brown, 1995) have important implications for the course design and it is very important to get as much information as possible from them (Richards, 2001). However, in this case this group cannot be accessed until these learners register for the course. Nevertheless, the following discussion will show how I aim to use this source when these participants are accessible.

To gather students’ needs and lacks in NA, often ‘I-Can-Do’ frameworks are used. However, such instruments can sometimes lead to the yielding of misleading data because it can only represent students’ perceived weaknesses. It has been argued that students are not always aware of their needs. For example, Basturkmen (2010) maintains that students are not always the best judges of their own needs. Ferris (in Basturkmen 2010, p.27), who carried out a study of 700 ESL learners, demonstrated that learners were unable to recognise their actual needs. Therefore, to evaluate learner’s present situation at the point of entry to the course, the learners would be given a placement test. This test will facilitate the selection process of the students, as they will require a certain level of English to benefit from the course. In this test the students will be required to write about their needs in a paragraph. This test will serve multiple purposes as it will not only show the students’ perceived needs but also provide a sample of their writing showing their actual needs. Additionally, the gap between the two will help the syllabus designer to design activities, which will make the learners see this gap. Discussing these needs with the learners during the course will also satisfy them. The course will be funded by the learners and it is important to satisfy them. Also, if the course is designed according to the need analysis but the learners do not consider those as needs then the course can have negative effects on their motivation. As Basturkmen (2010) maintains learners can become demotivated if the course does not seem directly related to their aims. For example, the main reason for enrolling for this course for these learners will be for preparing for IELTS exam and therefore they might not consider preparing for university writing skills as their need and might find it irrelevant. Belcher (2006) suggests discussing language needs with the learners can place their language learning needs in a larger context. Therefore, the knowledge about student perceived needs will help the teacher to negotiate their needs with them during the course. Also, the test will help the teacher to group the learners according to their language proficiency. This placement test will accompany a brief questionnaire asking the participants about their preferences, learner perceived needs, learning styles so that the activities can be designed according to their preferences and cognitive styles. (The placement test and all the questionnaires designed and administered in the study can be provided upon request).

Related literature to inform the NA:

The final source of information that plays an integral role in any NA is a review of the related literature. Basturkmen (2010) recommends locating published reports of ESP-oriented needs analyses in similar situations. The literature that informed this course design included Dickinson (2013), Al-Khairy (2013,) and Javid and Umer (2014). The literature also confirmed the survey findings and the most problematic areas of Saudi learners writing identified by these researchers were in consistence with that which were identified by the ESL instructors and IELTS examiners surveyed for the present study.

On-going and post-course NA

Although, this paper has only discussed the pre-course NA, which will influence the initial course design, there is now sufficient evidence to support the on-going need re-analysis for the revision of course design (Basturkmen, 2010). Any discussion of on-going NA and its implementation on this course is beyond the scope of this paper, however, it should be noted that once the course starts, students will be provided with weekly opportunities to assess their emerging needs and priorities. Questionnaires and open discussions in class, which have also been called buzz groups, will be used for formative assessment of the course. An end of course exam will be used for summative assessment of the course. A comparison of the students’ initial writings and these exam responses will be carried out to see if the course has met the desired outcomes. In addition, a questionnaire will also be part of the post-evaluation of the course. It will gather data concerning the appropriacy of the course material, teaching methods and other issues pertaining to the course delivery and will assess if any aspects of the course need to be modified. The consent of the participants will be obtained at all stages of NA and the participants will have an option to withdraw at any stage if they wish to do so.

Investigating Specialist discourse:

It has been argued that the content of a course needs to be based on a thorough and precise description of the language of the target situation. Hyland (2009) argues that a main source of data for writing research is writing itself. In the same vein, Basturkmen (2010) asserts the importance of investigating specialist discourse in order to teach the language the learners need to effectively communicate in their target situation. She (2010, p.45) enlists three approaches that can be used to investigate specialist discourse; these include ethnography, genre analysis and corpus analysis. This enquiry has combined the latter two approaches. Also, instead of embarking on empirical research into the specialist discourse, Basturkmen recommends investigating the discourse by using already existing resources to save time effort and resources. In line with her view, the researcher investigated British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE) and the model answers of the IELTS writing component. The literature that has already identified the key features of academic writing through register analysis was also consulted. For example, Jordan (1997 in Dudley–Evans and Johns 2002, p.227) enlists a number of characteristics of academic writing. This investigation into the specialist discourse enabled the researcher to see the gap between the present situation and the target situation of the learners.

Conclusions drawn from the NA

Following Hutchinson and Waters (1987) model of TSA and PSA, I was able to deduce the following information from the data gathered from the participants and the literature.

- The learners need to acquire particular academic writing skills to achieve high score in the IELTS test. Such as describing graphs, pie charts, procedures, argumentative writing, brainstorming etc.

- The learners need specific skills for the IELTS test. Such as writing to a word limit etc.

- The learners need to acquire academic writing skills to succeed in their studies abroad.

- They need to be familiar with the genres used in university writing and in the IELTS writing component.

- Their most immediate writing needs included vocabulary, ordering and organising ideas, formality and coherence.

It is important to note that during the course of the NA a large number of needs were identified, however, as Richards (2001) argues that needs have to be prioritised, decisions had to be made regarding which needs were critical and which were merely desirable.

DESIGNING THE COURSE AND SYLLABUS

Nunan (1998 in Gray 1990) suggests that an effective syllabus considers the learner needs, selects the linguistic items and decides what activities will promote language acquisition. The paper will now turn to the syllabus design stage of the project and present a rationale for choosing the approach.

Genre analysis as a base of syllabus designs:

Based on the above discussion of the NA, a course was designed using a genre-based approach to the teaching of writing skills. (For the course overview and syllabus see Appendix). There were several reasons for choosing genre analysis as the basis of this course. The literature on genre has highlighted that texts used in a particular environment demonstrate particular characteristics that make them distinct from the texts used in other contexts. The fact that a specific genre of text will have a prevalence of certain forms and lexis over several samples of such texts makes a case for using genre analysis as a base of syllabus design. This approach has been recommended by several researchers including Dickinson (2013) and Hyland (2006). Dickinson asserts that genre-based approaches have proven successful in improving writing in many other contexts and therefore should be employed to teach the IELTS writing component. This approach made the syllabus more relevant to the learners by giving high priority to the language forms these students would require in their future. Dickinson (2013) maintains that such teaching methodology does not only meet the learners’ most immediate need but also helps them to achieve various goals in the future. In the same vein, Dudley-Evans (2000) suggests that focusing on the specific features of the actual genres that learners actually have to write is the most efficient approach to teach a homogenous group. Considering this group is a homogenous one in a number of ways, choosing the genre approach for syllabus design will serve the learners’ needs effectively.

Another motive for using the genre-based approach is to foster learner autonomy in the students. Hyland (2006) argues that students in higher education have to engage with knowledge in new ways and are required to write in unfamiliar genres. As a result, despite acquiring a good score in IELTS exam, students often struggle in university studies. For example, feedback from overseas students in Australian universities illustrated that due to their unfamiliarity with the genre, essay writing was considered the most challenging task by them (Blundell, 2007, in Dickinson, 2013). Also, substantial differences, between the writing needed for the IELTS test and the real needs of university studies, have been noted by Moore and Morton (2007). This course, therefore, aims to introduce the learners to a wider notion of genre. They will be trained to notice patterns of language, which will enable them to look for common patterns when they encounter a new genre in their future studies. An ability to analyse the salient patters of their discourse will help them to produce similar texts. To sum up, a genre-based approach will prepare these learners to cope with unfamiliar genres in the future.

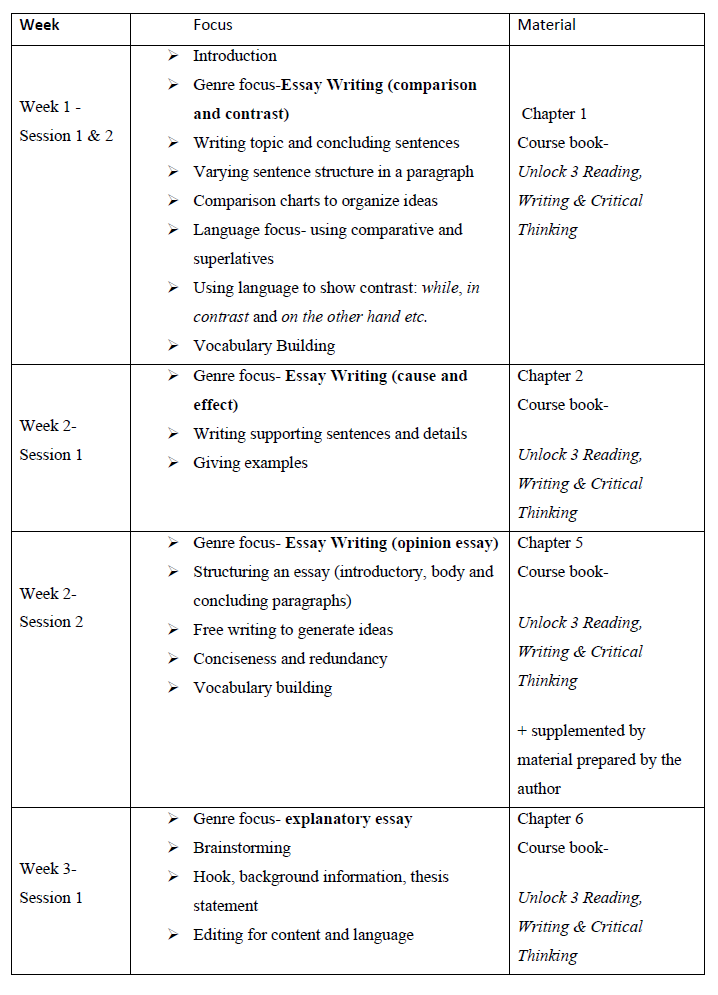

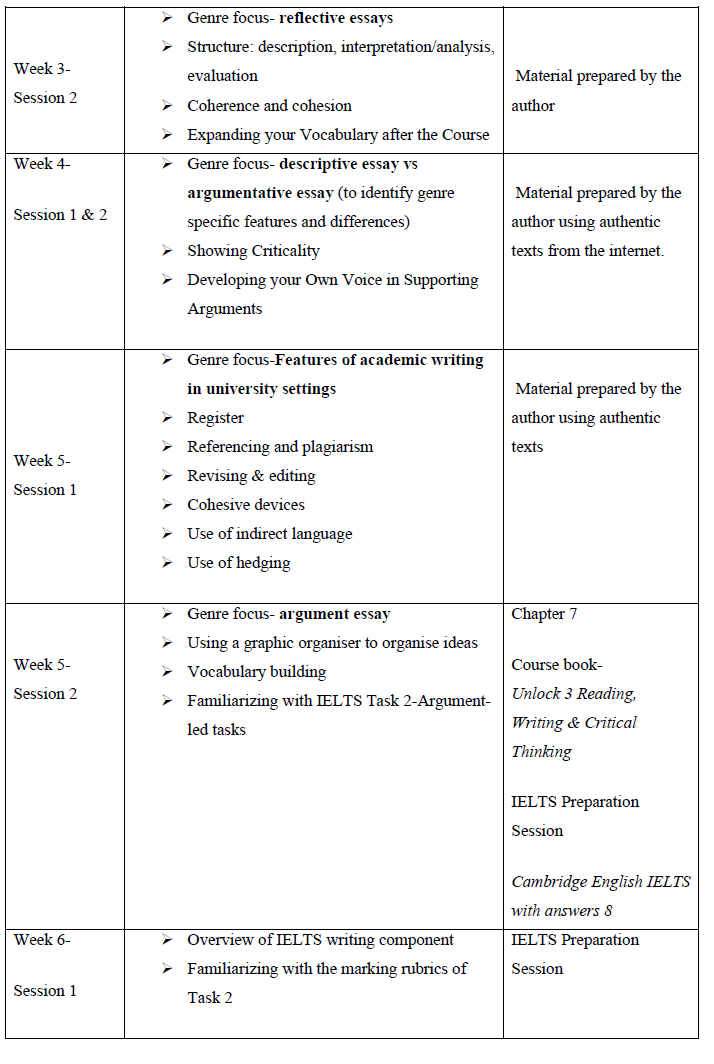

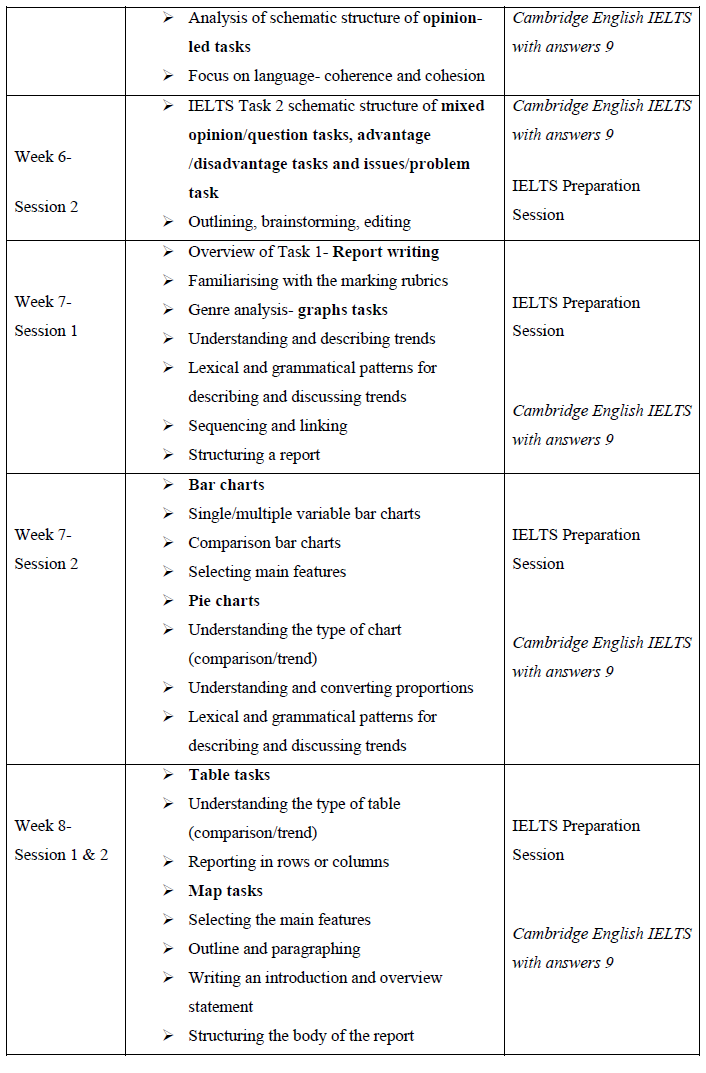

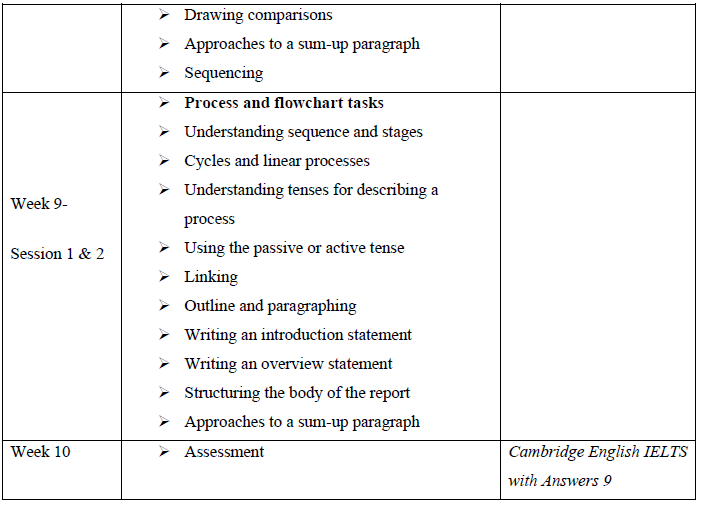

The course will introduce the learners to the common genres of academic writing. They will be trained to use appropriate schematic structures, vocabulary and grammar particular for academic writing. The students will also learn internalising and carrying out the stages of writing including brainstorming, organising, conferencing and redrafting. During the first five weeks of the course, the focus will be on academic writing in general, whereas during the last 5 weeks, the course will focus more explicitly on the English proficiency exam. During this second half of the course, in addition to learning skills particular to the exam, the student will also use and practice the knowledge acquired in the first part of the course. This structure will help to consolidate their learning and assist their long-term goals.

Course Material and evaluation

It is well known that selecting a suitable course book is not a simple task and requires careful consideration. Chambers (1995) discourages the use of intuitive decisions regarding this choice and provides a structured method of choosing course books. Similarly, Sheldon (1988) also provides a model for evaluating textbooks. Based on Sheldon’s model, I have chosen Unlock 3 for this course. Although course books have been criticised for their inability to meet a particular group’s needs (Allwright, 1981, O’Neil, 1982), there are several reasons for choosing a textbook for the course. Firstly, course books provide a framework to follow and they are cost and time efficient (O’Neil, 1982). Secondly, this textbook has been specifically designed for this learner community; it is culturally appropriate and meets most of their needs. Its educational validity is evident from the fact that in addition to improving their writing skills for English language proficiency tests, this book takes account of their broader education concern, and prepares them for tertiary education. For example, an inclusion of brainstorming activities and graphic organisers trains them for higher education. Wallace (1997) has noted the inability of the Middle Eastern students to think for themselves. He argues that as a result of traditional teaching methods focusing on memorisation, theses learners struggle with the writing tasks in the IELTS exam. Therefore, such activities will help them to write effectively in the future. Another feature of this book is that each of the chapters intensively teaches vocabulary, which was a major area of concern for these learners according to the survey findings. Also, each chapter aims to foster independent learning providing a progress log at the end of each chapter to give the learners a clear idea of his/her progression.

Using this course book as a framework, I aim to supplement this material with activities that take advantage of genre analysis more explicitly. Another reason due to which adaptation of some of the activities will be required is to suit learners’ styles and to prevent the lessons from being mechanical. Also, this material will have to be supplemented by IELTS preparation materials because although each chapter provides an examination focus, the strategies and skills provided are not specifically focused on the IELTS exam and therefore will have to be substituted by additional material. I will complement the course book with Cambridge English IELTS with answers 8 & 9. Using model answers from this book, I aim to incorporate activities, which will enhance their understanding of particular genres. This use of external texts from the learners’ particular discourse they are preparing for and adapting these texts for teaching the learners features of their discourse will meet the needs of these learners effectively. In summary, in accordance with O’Neil’s (1982, p.110) view, I would use the textbooks as a ‘jumping off point’ to provide only a base or a core of materials.

CONCLUSION

The course discussed in this paper was designed to respond to the needs of the Saudi students who were planning on going abroad for further studies. Their needs were investigated by conducting an NA using different sources and methods to triangulate the findings. The findings of the survey were confirmed by the relevant literature about the needs of these learners. Based on the results of the NA, the course syllabus was designed. The paper also discussed some other key issues such as material evaluation for the course. Finally, it is hoped that this study presents a good model that can be used for the learners in this context.

Address for correspondence: hira.hanif@kcl.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Al-Khairy, M. 2013. Saudi English-Major Undergraduates' Academic Writing Problems: A Taif University Perspective. English Language Teaching. 6(6), pp.1-12.

Allwright, R. 1981. What do we want teaching materials for? ELT Journal. 36(1), pp.5-17.

Khan, A. 2019. Designing ESP Texts for Engineering in the Saudi Context. English for Specific Purposes World. 58(21).

Basturkmen, H. 2010. Developing courses in English for specific purposes. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Belcher, D. 2006. English for Specific Purposes: Teaching to Perceived Needs and Imagined Futures in Worlds of Work, Study, and Everyday Life. TESOL Quarterly. 40(1), pp.133-156.

Brown, J. 1995. The Elements of Language Curriculum. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Newbury House.

British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE), Coventry University. [Online]. [Accessed 06 March 2015]. Available from: http://www.coventry.ac.uk/research-bank/research-archive/art-design/british-academic-written-english-corpus-bawe/

Chambers, F. 1997. Seeking consensus in course book evaluation. ELT Journal Volume. 51(1), pp.29-35.

Cambridge ESOL. 2013. Cambridge English IELTS with Answers 9. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cambridge ESOL. 2011. Cambridge English IELTS with answers 8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chazel, E. 2014. English for Academic Purposes. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

Cowling, J. 2007. Needs analysis: Planning a syllabus for a series of intensive workplace courses at a leading Japanese company. English for Specific Purposes. 26(4), pp.426–442.

Deakin, G. 1997. IELTS in context: issues in EAP for overseas students. EA Journal. 15(2), pp.7-28.

Dickinson, P. 2013. A Genre-based Approach to Preparing for IELTS and TOEFL Essay Writing Tasks. Journal of Niigata University of International and Information Studies. 16, pp.1-9.

Dudley-Evans, T. 2000. Genre analysis: a key to a theory of ESP? BÉRICA. 2, pp.1-11.

Gray, K. 1990. Syllabus design for the general class: what happens to theory when you apply it. ELT Journal. 44(4), pp.261-271.

Hillman, S. (2015). Basic Arabic for health care professionals. In: Trace, J., Hudson, T., & Brown, J. D. ed. Developing Courses in Languages for Specific Purposes. [online]. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, pp.35-47. [Accessed 6 January 2021]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/14573

Ho, K. (2015). Home care worker training for ESL students. In: Trace, J., Hudson, T., & Brown, J. D. ed. Developing Courses in Languages for Specific Purposes. [online]. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, pp.65-86. [Accessed 6 January 2021]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/14573

Hutchinson, T. and Waters, A. 1987. English for specific purposes: A learning-centered Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hyland K. 2006. English for Academic Purposes: An Advanced Resource Book. London Routledge.

Hyland, K. 2009. Teaching and researching writing English. 2nd ed. Harlow: Longman.

IELTS. 2012. IELTS | Researchers - Test taker performance 2012. [Online]. [Accessed 24 February 2015]. Available from: http://www.ielts.org/researchers/analysis-of-test-data/test-taker-performance-2012.aspx

IELTS. 2013. IELTS | Researchers - Test taker performance 2013. [Online]. [Accessed on 17 June 2020]. Available from: http://www.ielts.org/researchers/analysis_of_test_data/test_taker_performance_2013.aspx

Javid, C. & Umer, M. 2014. Saudi EFL learners’ writing problems: A move towards solution. Proceeding of the Global Summit on Education GSE 2014, 4-5 March 2014, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA. [online]. Taif, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Taif University. [Accessed on 17 June 2020]. Available from: http://worldconferences.net/proceedings/gse2014/toc/papers_gse2014/G%20078%20-%20CHOUNDHARY%20ZAHID%20JAVID_Saudi%20EFL%20Learners_%20Writing%20Problems%20A%20Move%20towards%20Solution_read.pdf

Lee, K. C. 2015. Mandarin Chinese for professional purposes for an internship program in a study abroad context. In: Trace, J., Hudson, T., & Brown, J. D. ed. Developing Courses in Languages for Specific Purposes. [online]. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, pp.100-114. [Accessed 6 January 2021]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/14573

Long, M. eds. 2005. Second language needs analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, T. & Morton, J. 2007. Authenticity in the IELTS academic module writing test: A comparative study of Task 2 items and university assignments. In: Taylor, L. & Falvey, B. ed. IELTS Collected Papers: Studies in Language Testing 19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp.197 -249.

Oh, Y. 2015. English for Specific Purposes for overseas sales and marketing workers in information technology. In: Trace, J., Hudson, T., & Brown, J. D. ed. Developing Courses in Languages for Specific Purposes. [online]. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i, pp.115–127. [Accessed 6 January 2021]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/14573

O’Neil, R. 1982. Why use textbooks. ELT Journal. 36(2), pp.104-111.

Richards, J. 2001. Curriculum Development in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sheldon, L. 1988. Evaluating ELT textbooks and materials. ELT Journal. 42(4), pp.237-246.

Trace, J., Hudson, T., & Brown, J. 2015. An overview of language for specific purposes. In: Trace, J., Hudson, T., & Brown, J. D. ed. Developing Courses in Languages for Specific Purposes. [online]. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘I, pp.1-22. [Accessed 6 January 2021]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/14573

Wallace, G. 1997. IELTS: global implications of curriculum and materials design. ELT Journal, 51(4), pp.370-373.

Westbrook, C., Baker, L., Sowton, C., Farmer, J. & Gokay, J. 2019. Unlock 3 Reading, Writing & Critical Thinking. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

Zughoul, M. & Hussein, R. 1986. English for Higher Education in the Arab World: A Case Study of Needs Analysis at Yarmouk University. The ESP Journal. 4(2), pp. 133-152.

APPENDIX

Syllabus: