Adverb-Adjective Collocation Use by Arab EFLLs and British English Native Speakers: a comparative corpus-based study

Supervised by:

Prof. Michael Ingleby, Dr. James Wilson and Prof. James Dickens

Linguistics Department, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies, University of Leeds

ABSTRACT

This research paper is a comparative corpus-based study of the use of written lexical collocations amongst British native speakers and Arabic speaking learners of English. It presents the findings of an investigation into L1 interference based on error analysis theory underpinned by a corpus-based study. Collocation is an aspect of language learning that poses considerable difficulty for English Foreign Language learners (EFLLs). Arab EFLLs, as do EFLLs from any other first language (L1), encounter various problems when producing collocations. To investigate the written production and the source of errors or strangeness that could be an influence of the learners’ L1, I have implemented a frequency corpus-based analysis and error analysis of the use of the Adverb-Adjective collocation. The results reveal that Adverb-Adjective collocation is less used among Arabic speaking EFLLs than among British native English-speaking students and feed directly into the teaching of English to Arab (and other) learners of English and argues for a corpus-based approach to teaching collocations.

KEYWORDS: Adverb-Adjective, Arab EFLLs, Corpus-based, Error analysis, Frequency, Lexical collocations, L1 interference

INTRODUCTION

Collocation has long been a subject of great interest across a wide range of branches of linguistics, such as corpus linguistics, sociolinguistics, and cognitive linguistics (Granger, 2003; MacArthur and Littlemore, 2008; Regan, 1998). Since the early 1980s, a growing body of literature has investigated the use of English by foreign language learners (EFFLs), with particular attention to the use of lexical collocations (Al-Zahrani, 1998; Bahns and Eldaw, 1993; Bartsch, 2004; Biber and Barbieri, 2007; Chang, 2018; Nesselhauf, 2003; Siyanova and Schmitt, 2008). This is evident in the increased interest in investigating the use of lexical collocations by EFLLs with different first languages (L1), for example, Turkish EFLLs (Basal, 2017; Demir, 2017), Korean EFLLs (Chang, 2018), Hebrew EFLLs (Laufer and Waldman, 2011) and Arabic speaking EFLLs (Alharbi, 2017; Bahumaid, 2006; Farooqui, 2016; Khoja, 2019; Mahmoud, Abdulmoneim., 2005). Producing accurate or appropriate collocations in spoken or written language is viewed as a complicated aspect of language learning (Farrokh, 2012). Many EFLLs encounter difficulties with putting words together, especially with, producing collocations in the way that native speakers do (Bahns, 1993; Nugroho, 2015). Problems associated with combining words in the L2 emphasise the need to investigate the use of collocations by EFLLs. Native speakers of English find that ‘strong tea’ sounds right, rather than ‘powerful tea’, while Arabic speaking EFLLs may say ‘heavy tea’ to mean ‘strong tea’ as a result of L1 interference. The acceptability of a co-occurrence is difficult to justify in terms of producing possible versus impossible collocations, because any combination of words is theoretically possible (Auer, 1997). Native speakers’ intuition and language exposure play a crucial part in creating an acceptable collocation (Durrant and Schmitt, 2010; Martinez and Schmitt, 2012). The production of collocations may be further influenced by L1 interference because some combinations of words sound appropriate in the L1 but not in the L2.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Several definitions of collocation are proposed in the literature (Manning et al., 1999; Mel’čuk, 1998). Firth (1957), recognised as the father of collocation, defined it as words that co-occur habitually, thus creating a particular meaning in language production. Firth states that knowledge of a word is accompanied by a familiarity with the words it accompanies which could be described as collocability between words; for example, the way ‘dark’ collocates with ‘night’. The common definition for collocation from a statistical perspective indicates that there has to be something related to numbers/frequency, or that there has to be a certain degree of probability of two words co-occurring within a short distance (e.g. ‘appreciate’ and ‘sincerely’). One way of identifying collocation is by considering its probability score (e.g. log-likelihood (LL)) as being a standard collocation, for example, ‘sincerely hope’ has a 185.13 LL score based on the BNC; thus ‘sincerely’ is a probable collocate of ‘hope’. Using corpora can have a significant benefit for linguists as they can, within seconds, generate more collocations than a native speaker would ever be able to do. More importantly, these collocations can be ranked according to the various statistical associations (e.g. frequency or probability). Sinclair (1991) and Hunston (2002) concur in noting that collocation refers to the position of words close to each other in the text. The definitions provided here illustrate a frequency-based approach to studying collocation. For the purpose of this study, I define collocation as:

A combination of two words in which the occurrence of one word is conditional on the presence of the other (for example an Adverb-Adjective collocation is a combination of an adverb and an adjective with the adjective conditioned by the adverb).

Adverb-Adjective collocations are used to explain a purpose, ascribe degree, or other qualities to an adjective (e.g. ‘utterly ridiculous’ or ‘deeply concerned’). As preposition or function words do not typically occur between Adverb-Adjective collocations, this study focuses on lexical collocations: word combinations that exclude any prepositions or intervening function words (e.g. ‘absolutely delighted’ and ‘really amazing’ (Mel’čuk, 1998; Phoocharoensil, 2013)).

It is assumed that native speakers’ knowledge of collocation is not reliable in terms of producing an extensive list of collocations when compared to those automatically listed in large corpora. A computer will generate long lists of collocations ranked by probability, but language instructors usually need to refine these lists, remove any unusual forms, and pick out the most pedagogically relevant collocations. The main advantage of a computer-generated list of collocations is that it allows to get the most probable collocation which could be pedagogically the most relevant. Foreign language learners aim to achieve an acceptable use of collocation to make their writing more natural and accurate to native speakers, and for general and educational communication purposes, yet this requires language exposure (Henriksen, 2013). For example, the choice of the right lexical collocate is important to sound natural to a native speaker as in ‘high’ versus ‘tall’ (e.g. one can say ‘tall man’ but not ‘high man’). The right choice of adjective is needed to sound natural, as in ‘international food’ versus ‘worldwide food’. By using corpus data tutors can identify more contrastive pairs and develop exercise around them which is an example of a hand-off corpus-based language learning. Teaching contrastive pairs would assist in learning collocations and language development in order to produce natural language or at least to be acceptable to native speakers (Demir, 2017). The term naturalness explains a well-formed use of English that may sound acceptable to native speakers of that language.

It has been established through various Arabic authors that the Arabic language is rich in collocations, yet some scholars stated that the adverb-adjective collocations does not exist in Arabic (Abd Ai-Qadir, 2015; Ghazala, 1993; Husamaddin, 1985; Mustafa, 2010). Brashi (2005), an Arab linguist, included the Adjective-Adverbial phrase in his classification. The adverbial phrase, in Arabic, consists of a preposition and a noun e.g. مستنكرٌ بشدة ‘mustnkrun bishdatan’ (meaning strongly condemns). Brashi’s classification, however, may be problematic, as seen by the fact that when translated into English his example creates an Adverb-Verb collocation in English and Arabic grammar, which supports the argument for the absence of the Adverb-Adjective collocation in Arabic. Although some previous studies claim that Adverb-Adjective collocations may not exist in Arabic, there are some instances of Adverb-Adverb collocations as in ‘wholly and heartedly’ (بالتمام والكمال ) and Adjective-Adjective collocations as in ‘healthy and well’ (بصحه وعافيه); yet these collocations are usually connected with a connector such as ‘and’ (Rabeh, 2010).Therefore, based on the literature, there is no direct equivalent for the English Adverb-Adjective collocation in the Arabic language; this absence is thus likely to hinder learners’ collocational development.

Previous Studies in the Use of Collocations in EFL

Previous literature on AEFLLs’ use of lexical collocations has highlighted several difficulties in producing accurate collocations. Mahmoud (2005) found that AEFLLs tend to produce lexical collocation errors accounting for 83% of the total collocation errors in his study, of which most display an incorrect selection of lexical items. The following examples are highlighted by Mahmoud in his 2005 study as errors attributed to negative transfer from the learners’ L1. The first is where the learners misuse one word; for example, the learners would say ‘artificial information’ instead of ‘faulty information’, or with both words incorrect, for example, ‘basic machine’ instead of ‘important device’. These four examples may be mis-translations from learners’ L1, but they are not incorrect collocations in English. Also, Mahmoud highlights contextual errors, linguistically correctly formed, but incorrect in context; for example, ‘bring a boy’ instead of ‘give birth to a boy’. Though the previous examples are linguistically well-formulated and correct, the exact meaning in context differs because the student was talking about the process of giving birth which could be expressed in Arabic as ‘bring’ or ‘put’ تَضعُ /tad'u/ not ‘give birth to’. Thus, the choice of the right lexical collocation is as essential as forming linguistically acceptable collocations (e.g. giving a positive or negative connotation which will be discussed below). Another error highlighted by Mahmoud is word-formation errors where one part of the collocation is used in the incorrect form; for example, ‘wants to get marriage’ instead of ‘wants to get married’. These errors could be attributed to negative interlingual transfer which may be L1 influence on the L2. Rajab et al. (2016) investigated Libyan Arab EFLLs’ semantic written interlingual errors in which, he argues, direct transfer from Arabic was one of the causes of errors. Alanazi’s (2017) investigation into Saudi EFLLs’ knowledge of producing synonyms in English as translations of Arabic were similar to Rajab et al.’s (2016) results, in that he found that L1 is one source of errors that had influenced the production of synonyms and collocations. The most interesting relevant finding was the frequent use of the adverb ‘very’ in cases where ‘extremely’ and ‘completely’ should be used such as (‘very cheap’ instead of ‘extremely cheap’) and (‘very useless’ instead of ‘completely useless’). The use of different degree adverbs would imply a negative connotation in contrast to how native speakers deliver it which, therefore, would hinder EFLLs’ language development in terms of using collocations.

An example is the collocation ‘very cheap’ as in ‘the flight was very cheap’, which implies a positive connotation that it is a good price or affordable; however, the adverb ‘extremely’ is used in ‘her clothes were extremely cheap’, because ‘very cheap’ can carry the negative connotation that the product or item did not cost much because it looks cheap. The participants opted for using ‘very’ instead of ‘extremely’ and ‘completely’ as these two adverbs in Arabic جداً and كثير can be used interchangeably, both words meaning ‘very’ without affecting the intended meaning of the collocation. However, he further explains that the adverb ‘very’ is not appropriate in some contexts, such as in ‘very aware’ instead of ‘fully aware’, which justifies some errors that could be caused by L1 interference. Alanazi argues that there is a particular difficulty with sense relations (e.g. synonyms) among AEFLLs from Saudi Arabia that needs to be investigated in future research. There is also a large amount of research that identified L1 influence as one of the major sources of written English errors for AEFLLs (Abushihab et al., 2011; Hago and Ali, 2015).

Corpus Linguistics

The term Corpus Linguistics first appeared in the early 1980s (Leech, 1992); however, as a linguistic method, it was first adopted for such purposes in the late 1950s (McEnery and Hardie, 2013). A corpus, in linguistics, is a collection (a body) of texts. Many modern definitions emphasise the fact that corpora are accessed on a computer — a collection of naturally occurring texts or recordings of language that are machine-readable and can be accessed and analysed through specialist software packages designed for linguistic purposes (Kennedy, 2014; McEnery and Hardie, 2011). Types of corpora vary in form and purpose (Hunston, Susan., 2002), such as specialised corpora, general/reference corpora, comparable corpora, parallel corpora and also learner corpora, which form the basis of this study. The terms ‘learner corpus’ and ‘reference corpus’ need to be defined here, as these corpora are used in this study and referred to several times in this paper. A learner corpus contains samples of learners’ language production: that is, either spoken or written data to illustrate learners’ use of particular linguistic phenomena and identify typical errors. A reference corpus is a large standard corpus, consisting of a wide range of text types (e.g. literary, technical, journalistic). Reference corpora are often used in comparative studies as the reference guide for the use of a specific language.

A considerable amount of literature has been published on the written production of English by Arabic EFLLs (AEFLLs) which has employed traditional quantitative or qualitative methods in their analysis (Aldera, 2016; Alsied et al., 2018; Izwaini, 2016; Mahmoud, Abdulmoneim., 2005; Rajab et al., 2016; Sabah, 2015; Tahseldar et al., 2018). These traditional methods mainly involved manual identification and classification of collocations. The corpus approach offers a new perspective on language use that cannot be performed through the traditional quantitative approach (TQA) as it analyses a large amount of linguistic data quickly and easily (Hunston, Susan., 2002). Also, the corpus approach enables linguists to empirically investigate syntactic relations between words through syntactically annotated corpora (Gries, 2013). The corpus approach enables the researcher not only to identify topics through thorough analysis but also to generate lists of collocations or expressions automatically (further discussion is given in the second paragraph of page 5); it permits automatic investigation by providing actual measures/frequencies of all instances within the whole corpus (Gilquin, 2005). Unlike the traditional approach where learners’ errors need to be identified manually, corpora can be tagged to identify common errors. Corpus interfaces typically provide some basic statistical measures (e.g. absolute and normalised frequencies, mutual Information, log-likelihood score and the t-score). Once the collocations have been identified, complex statistical tests can be run with automatic programming to provide various association measures for collocations.

There is an increasing demand among Arabs to learn English as a foreign language, not only for educational purposes but also for business and international travel. It is thus essential to investigate the influence of Arabic on learners’ use of lexical collocations. The main focus of this paper is on the use of lexical collocations by AEFLLs through a corpus-based approach. So far, a few researchers have investigated AEFLLs’ usage of Adverb-Adjective collocation from a corpus-based frequency approach (Alharbi, 2017; Farooqui, 2016). In this paper, I investigate the L1 interference of Adverb-Adjective collocation use among Arabic speaking learners of English based on error analysis theory through a corpus-based study of Adverb-Adjective collocations.

Research questions

This paper acts as a preliminary study for the methodology to be implemented in my PhD thesis and considers only the Adverb-Adjective collocation set. I seek to answer the following questions:

1. Are there any statistically significant differences in the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations between AEFLLs and NBES?

2. Are there any statistically significant differences in the use of Adverb-Adjective collocation by AEFLLs that could be attributed to L1 interference?

Based on the above research questions, the following hypotheses were formulated to test first whether being a native speaker of English affects the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations and, second, whether L1 interference has an effect on Arabic speaking learners’ use of Adverb-Adjective lexical collocations:

- First null hypothesis (H10): There is no difference in Adverb-Adjective collocation use between AEFLLs and NBES.

- Alternative to first null hypothesis (H1A): There is a difference in Adverb-Adjective collocation use between AEFLLs and NBES.

- Second null hypothesis (H20): Arabic as an L1 does not affect learners’ performance in using Adverb-Adjective collocations in English.

- Alternative to second hypothesis (H2A): Arabic as an L1 has an effect on learners’ performance in using Adverb-Adjective collocations in English.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This is an investigation into L1 interference based on error analysis theory underpinned by a corpus-based study. L1 interference theory is an approach to explaining the L1 influence on production in L2. L1 interference, usually referred to as L1 transfer, L1 influence, or cross-linguistic influence, commonly refers to the L1 influence on grammar or intended meaning in the target language which could lead to interlingual errors (Hashim, 2017). Previous studies of L1 influence have shown two outcomes of this process, known as positive and negative transfer - the latter leading to interlingual or intralingual errors (Al-Khresheh, 2010; Hashim, 2017; Khansir, 2012). Positive transfer usually occurs when, due to linguistic similarities between the two languages, learners depending on their L1 background create a well-formed, successful utterance in the target language. As for negative transfer, it results from learners’ attempts to rely on their L1 linguistic background when using the second language which leads to transfer errors, both interlingual (attributable to the learners’ first language) or intralingual errors (attributable to the language being taught).

The second theory is based on a framework of what I shall call ‘Contrastive Error Analysis’ (CEA) combining Lado’s (1957) contrastive analysis (CA) framework and Gass and Selinker’s (2008) Error Analysis (EA), to which some modifications have been made to generate data for this study (See Table 1). Error analysis was first introduced by Stephen Corder who viewed L2 errors as an interesting element that can reveal many linguistic issues (1967). EA theory emerged as a reaction to the criticism made of CA. This method of analysis is particularly useful when investigating the sources and causes of learners’ errors, e.g. L1 interference (Khansir, 2012; Richards, 1971). The combination of both frameworks allows a comprehensive analysis of Arabic speaking Learners’ use of Adverb-Adjective collocations. In this study, I deliberately merged the two frameworks, CA and EA, to avoid much of the criticism made of adopting one of the two frameworks independently. The advantage of this particular method is mainly that the comparison between two languages is not a ‘straightforward comparison of structure’; it is rather a complex comparison comprising many hierarchically ordered difficulties (Gass and Selinker, 2008; Lado, 1957). Those hierarchically ordered difficulties, as highlighted by Gass and Selinker, are differentiation, a new category, absent category, coalescing and correspondence (2008). The first occurs when there is more differentiation in L2 than in L1 (e.g. a form in L1 can be said in multiple forms in the L2). The second, new category, occurs when the second language has a form that is unknown in the learner’s first language. The third difficulty, absent category, occurs when there is an absence of one of the L1’s rules in the L2. The fourth, coalescing, is observed in instances when the opposite of differentiation occurs. The last category, correspondence, usually occurs when both languages have forms that are used similarly.

Another reason for merging the two frameworks has to do with the nature of this study. As it is empirically based, this should validate the results of the hypotheses being tested in this study, and compensate for the fact that Lado’s framework is insufficiently empirical, as it involves creating a list of potential problems before checking to see if those problems actually exist. Lado (1957) stated that:

The list of problems resulting from the comparison of the foreign language with the native language […] must be considered a list of hypothetical problems until a final validation is achieved by checking it against the actual speech of students. This final check will show in some instances that a problem was not adequately analysed and may be more of a problem than predicted.

From my point of view, shared with many other scholars, collocation is a key element within a language that requires a complex level of language proficiency (Shammas, 2013; Siyanova and Schmitt, 2008). Most of the studies of EFLLs have shown that using collocations poses a difficulty for language learning production, as these central elements of a language require a knowledge of L2 grammar, i.e. correctly placing vocabulary in a sentence (Al-Zahrani, 1998; Alangari, 2019; Laufer and Waldman, 2011). Also, their correct use is indicative of a level of language proficiency being that of a near-native speaker; the more learners produce correct collocations, the more proficient they appear to be in that language (Siyanova and Schmitt, 2008). The use of lexical collocation has received a lot of research attention as it is viewed as troublesome not only for language learners but also for translators (Mahmoud, Abdulmoneim., 2005; Nesselhauf, 2003).

One noteworthy example, related to the main objective of this paper, is the set of rules for using adverbs in Arabic; in English, the adverb precedes the adjective it modifies, which is not the case in Arabic. To illustrate this, Diab (1997) performed an error analysis study on Lebanese EFL students’ written essays in which he found word-order errors, specifically in the placement of adverbs. For example, ‘every person almost has a car’ (almost every person has a car). The Arabic version of this sentence is:كل شخص تقريبا لديه سيارة. There are many possible ways to formulate the sentence above in Arabic (the adverb almost in the previous example can be placed at the beginning, middle or at the end of the sentence); but in English, the adverb ‘almost’ should be placed at the beginning of the sentence, so the error is caused by L1 transfer.

Most recent literature agrees that adverbs are the most difficult syntactic category for AEFLLs (Al-Shormani and Al-Sohbani, 2012; Rajab et al., 2016), possibly because AEFLLs copy the rules for the placement of adverbs from their L1 to the L2. The difficulty of adverbs is a common problem for EFLLs in general (Yilmaz and Dikilitas, 2017). Unlike English, Arabic is a ‘free word order language’ in which this kind of sentence could have four different word orders (Al Aqad, 2013):

- Subject (S) - Verb (V) - Adverb (Adv),

e.g. the machine operates quickly – الالةُ تعمل ُبسرعةٍ

- Verb (V) - Subject (S) - Adverb (Adv),

e.g. operates the machine quickly – تعملُ الالةُ بسرعةٍ

- Verb (V) - Adverb (Adv) - Subject (S),

e.g. Operates quickly the machine – تعملُ بسرعةٍ الالةُ

- Adverb (Adv)- Verb (V) - Subject (S)

e.g. quickly operates the machine – بسرعةٍ تعملُ الالةُ

The Adverb can be placed in the initial, medial (in sentences containing verbs), and final position, creating four possible positions within Arabic sentence structure, which explains the source of difficulty for AEFLLs using adverbs. Al Aqad has pointed out that there is a particular difficulty in placing adverbs in English due to the flexibility of their positions in Arabic, in which they can occur before or after adjectives or verbs, which presents several possibilities for potential errors caused by L1 interference (2013).

METHODS

This is a preliminary study aiming to analyse the use of Adverb-Adjective English collocations used by AEFLLs and to use the results of that analysis to make judgements about the validity of the L1 interference hypothesis. It is a comparative corpus-based study which compares Arabic-speaking learners’ data with actual and authentic instances of language use by students who are native-speakers of English. In this case the British Academic Written English (BAWE) corpus of native British English students’ (NBES) academic written English to provide reliable evidence for the claims made in this study.

Related terms to the methodology

In the following sub-sections, I briefly explain and put into context terminology referred to throughout the study - such as raw and normalised frequency, token and type.

Raw frequency (RF) and Normalised frequency (NF)

The term frequency refers to the number of instances occurring within a particular data set. Two frequencies will be reported: raw frequency and relative/normalised frequency. Raw frequency is commonly referred to as an absolute frequency, representing the actual number of occurrences of an instance, commonly reported when considering one corpus. Raw frequency is calculated through the following formula:

Total occurrence of (x) in a corpus ÷ Total number of words in a corpus

Relative/normalised frequency is usually reported when comparing two or more corpora of different sizes. Normalised frequency is usually presented as the number of instances per million words (ipmw) and calculated through the following formula:

Raw frequency = (Total number of words in a corpus) x 1,000,000

(Evison, 2010; McEnery and Hardie, 2012).

Token and Type

Token and type are two terms that need to be clarified when talking about word frequencies in a corpus. Token and type are terms used to refer to a particular relation between lexical items in a corpus (Lennon, 1991). Both represent the number of words in a corpus (Hunston, Susan., 2002; McEnery and Hardie, 2012). On one hand, a token refers to the total number of words in a corpus ignoring the number of repetitions of each word, and often includes punctuation marks. Type, on the other hand, refers to the number of distinctive words in a corpus (see Table 2 for detailed information about the number of tokens and types for the learner corpora used in this paper). To clarify the distinction between the two terms, the sentence, ‘To be or not to be; that is the question’ has eight types and 10 tokens since type disregards the number of repetitions of the words ‘to’ and ‘be’ in the example.

Data analysis

In this study, I have tried to investigate the frequency differences between the use by AEFLLs and by NBES of Adverb-Adjective collocations. The second aim of this study was to investigate the influence of Arabic as an L1 on the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations by AEFLLs. Therefore, two methods of analysis have been adopted to answer the two research questions; frequency-based analysis and error analysis. Frequency-based analysis identifies the commonly used Adverb-Adjective collocations based on their occurrence. This first approach will provide the baseline data for the comparison. The second approach will use the collocation output from the first research question to investigate L1 interference following the error analysis analytical framework.

Procedure

The initial step in the preparation of this paper was to collect a list of the top fifty most frequently occurring Adverb-Adjective collocations within the Arabic speakers’ corpus to be compared with the list of the top fifty collocations in the BAWE corpus. Due to the insufficient number of instances of the AEFLLs use of Adverb-Adjective collocations within the Arabic speakers’ corpus (only 63 instances in total), I have adopted another procedure to compile additional data that displays AEFLLs’ use of Adverb-Adjective lexical collocations; these specifically focused on the use of adverbs ending with -y (very) and -ly. Using the Wordlist function in Sketch Engine, the 100 most frequent adverbs were retrieved from the BAWE. These 100 adverbs also occur on the top 100 adverb Wordlist in the BNC using Sketch Engine. Then, a search was made on each adverb for its adjective collocates, as those adverbs were used as a baseline for comparisons between AEFLLs’ use and native speakers’ use. These two steps assisted in generally generating more examples of learners’ use of lexical collocations. The collocation lists were then analysed to identify whether there is an Arabic L1 influence that affected AEFLLs’ use of Adverb-Adjective collocations.

It is important to talk about the collocation extraction procedure as there is no agreement over the frequency cut-off point for collocation extraction in the literature, as it is said to be ‘somehow arbitrary’ (Biber and Barbieri, 2007). Nonetheless, most agree on focusing on instances that have at least a frequency of ≥ 20- 40 ipmw within written data (Biber and Barbieri, 2007; Biber et al., 2004). For example, Siyanova and Schmitt (2008) investigated the use and processing of Adjective-Noun collocations in a multi-study perspective. They extracted 810 instances for L2 learners and 806 instances for native speakers. They then consulted the BNC to classify the collocations into four groups based on frequency-occurrence bands:

1. Group 1: contains collocations that occurred between 1-5 times in the BNC;

2. Group 2: contains collocations that occurred 6-20 times in the BNC;

3. Group 3: contains collocations that occurred 21-100 times in the BNC;

4. Group 4: contains collocations that occurred >100 times in the BNC.

The selection criteria vary in the literature, on one hand, Chen and Baker (2010) and Ädel and Erman(2012) focused on lexical bundles and word combinations respectively by setting the frequency cut-off point at 25 ipmw. On the other hand, in Laufer and Waldman (2011) a minimum frequency of 20 ipmw or more was considered adequate to investigate the use of Verb-Noun collocations by Hebrew students of English, with the 220 most frequently occurring nouns. This being said, the present study shows a small number of collocations that have an occurrence of >20 ipmw, therefore I have provisionally set the frequency range at 6-200 ipmw in the Arabic speakers’ corpora. This has generated a list of 20 collocations to be compared against the native use.

Software and Packages

This study was carried out concurrently using both the IntelliText and Sketch Engine web interfaces to extract the widest range of possible usages of Adverb-Adjective collocations. A major reason for working with both web interfaces was due to a specific weakness in the Word Sketch tool in Sketch Engine which does not allow users to search for specific adverbs in the BAWE corpus. The Sketch Engine support team replied to an email enquiry that it would not be possible to search for adverbs in the BAWE corpus via this web interface as ‘this corpus was processed by a different tool than the other corpora and [they] do not have sketch grammar for as many parts of speech as in the other case’ (V Ohlídalová 2019, personal communication, 1 November). Another motive for using both web interfaces was that, in combination, they offer a range of association measures for collocation extraction, for example, the raw frequency for each word within the collocation, t-score and log likelihood. The data compiled will be tabulated in Excel files.

The findings were analysed statistically through the Statistical Package for Social Science program (SPSS). Significance and descriptive statistical tests were calculated such as the p-Value, mean scores, median, and standard deviation.

Corpora selected

Learner corpora

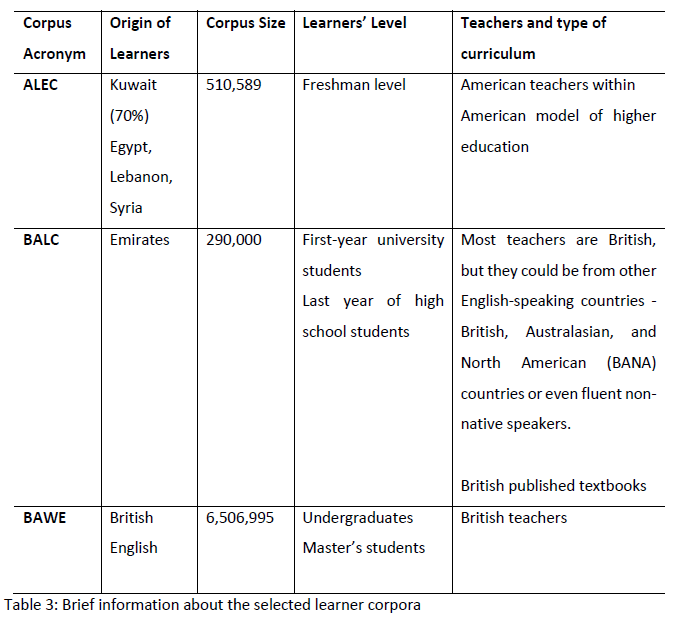

The two learner corpora compiled for this study were one for the AEFLLs and the other an academic corpus for the NBES. Detailed information about each corpus is given in Table 3 below.

The Arabic speaker corpus (henceforth referred to in the plural form) consists of data from two independent corpora of AEFLLs which come from the:

- Arabic Learner English Corpus (ALEC) in Kuwait, and the

- British University in Dubai (BUiD) Arab Learner Corpus (BALC hereafter) in Dubai, UAE.

Based on direct contact with the compilers of both corpora, the majority of learners were:

- Arabs from Kuwait for the ALEC and Emiratis for the BALC, with some presence of other Arab nationalities in the ALEC;

- All around the same age.

Despite the fact that the data were collected from two Arab countries, the learners in both, as well as the native corpus, were mostly from the same age group. For the native speakers of English, one corpus will be used:

- British Academic Written English (BAWE) Corpus.

The data is compiled from native speaker English students from Britain who belong to the same age group.

Table 2 presents information about the size of both corpora in terms of the number of tokens and types. The native speaker corpus has a larger store of words, both tokens and types, while the AEFLLs corpora have fewer tokens and types. There is a huge difference between the AEFLLs and NBES in terms of type and token numbers. Though one limitation of the AEFLLs corpora size is that it is small when compared to the BAWE corpus, it still provides enough data for a robust analysis. Given the fact that the size of the two corpora is not identical, the AEFLLs corpora (883,141words) and the BAWE corpus (6,968,089 words), the first step for processing the data is calculating the normalised frequencies. The base of normalisation in this study was per 1,000,000 words. The formula for normalization per 1,000,000 words (pmw) is as follows:

![]()

Where, is the normalised frequency, is the absolute frequency, and C is corpus size in words.

Reference corpus

Due to the nature of the research being a comparative corpus-based study, there is also the necessity to use an English reference corpus. A reference corpus is usually referred to as the ‘general corpus’ defined as containing a balanced representation of a given language. The typical balanced representation in the reference corpus is seen in terms of the genres and domains of the language considered (McEnery et al., 2006). In this case, I used the British National Corpus (BNC), a 100-million-word corpus of written and spoken British English collected from the 1980s to 1993. The BNC is used as the baseline for choosing the adverbs in this study. Therefore, to improve the reliability of the experimental design, the top 100 adverbs in the BAWE corpus were checked against the top 100 adverbs in the BNC. The BNC is large enough to be representative of the English language to be compared with the written essays of both datasets.

RESULTS

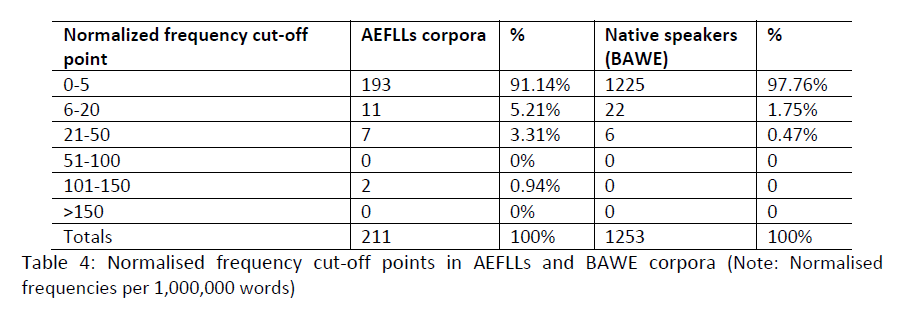

In the first research question I aim to identify any statistically significant differences between AEFLLs and NBES in the use of Adverb-Adjective collocation. I compared the number of collocations extracted from both corpora, which suggests the first significant difference; there were 211 and 1253 instances in total for the AEFLLs and British students respectively (see Table 4). The total numbers suggest that the AEFLLs use fewer Adverb-Adjective collocations than the NBES do. This is also clear in the number of collocations list for the AEFLLs where 193 collocations out of the 211, accounting for 91.14%, only have a single occurrence.

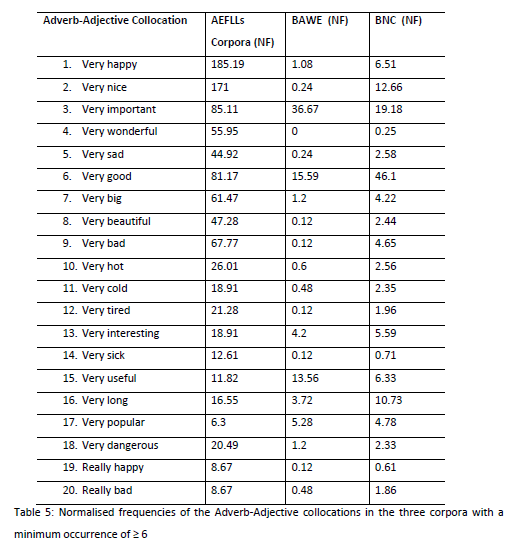

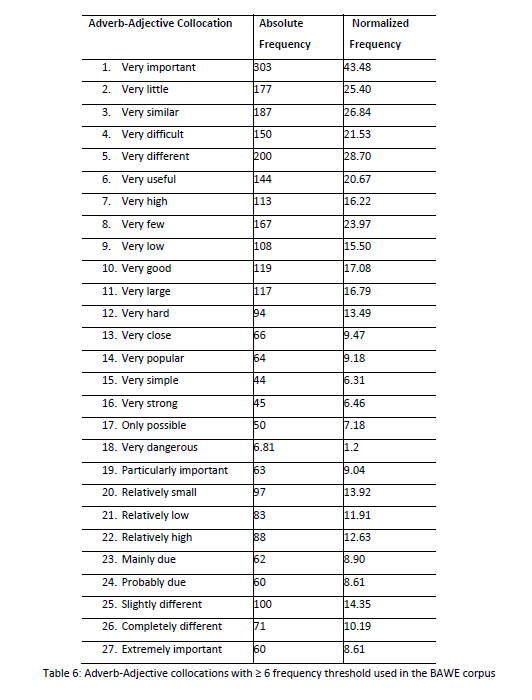

Setting the normalised frequency threshold of (f ≥ 20) would restrict the study to only nine collocation sets for the AEFLLs and six for the NBES. The threshold was thus set to f ≥ 6 as a minimum frequency threshold generating 20 collocation sets for the AEFLLs and 28 for the NBES. The 20 collocations for the AEFLLs are presented along with their normalised frequencies, in both learner corpora and the BNC, being the English reference corpus (see Table 5).

Table 5 below illustrates that all the collocations listed have a higher frequency of occurrence in the AEFLLs corpus, which is an unexpected result of the comparison between the two.

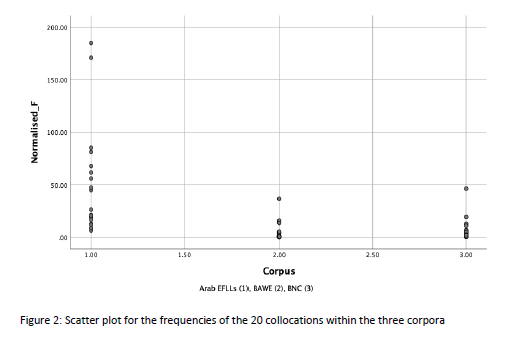

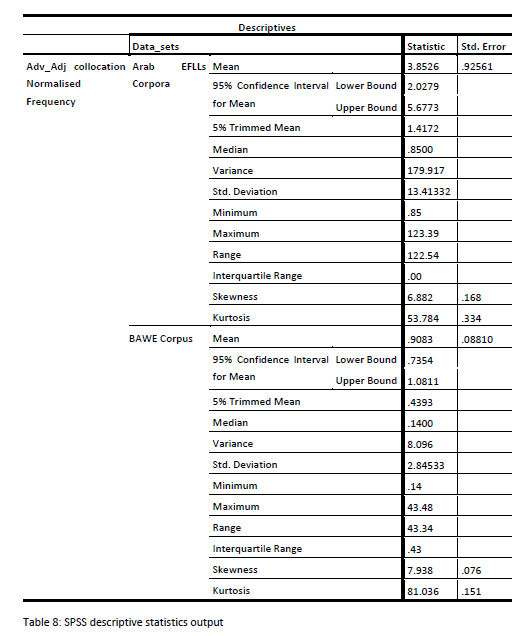

A visual examination of the box plot and the scatter plot graph revealed that the sample data were not normally distributed, but positively skewed (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 below). The degree of skewness requires a non-parametric test to examine the statistical difference between the three data sets.

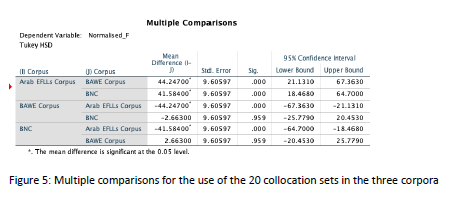

The Kruskal-Wallis H test was applied to analyse the differences between the three corpora in terms of the use of the 20 collocations listed in Table 5. The Kruskal-Wallis H test is a non-parametric test based on ranks, used to determine the decision parameter between groups of more than two (Kruskal-Wallis H Test using SPSS Statistics, n.d). The Kruskal-Wallis H test illustrated that there was a statistically significant difference in the use of the 20 collocations amongst the three corpora, H-statistic = 35.555, p = 0.000, with a median rank of 47.95 for the AEFLLs corpora, 16.55 for the BAWE and 27.0 for the BNC (see Figure 2).

Figure 3: Kruskal-Wallis H test SPSS output[1]

This implies that variability in the ranks for the two groups (AEFLLs data and BAWE data), would be close to a significant effect based on the partial eta-squared result in which η2> 0.319 (See Figure 4), which is a substantial effect based on the suggested norms for partial eta-squared (Privitera and Mayeaux, 2018). In conclusion, 31% of the variability is significantly higher than the percentage expected by chance p < 0.000 (η2 = 0.319). Thus, this result leads to rejecting the first null hypothesis, H10, concluding that there is a statistically significant difference between AEFLLs and the NBES in terms of the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations, H-statistic =(p>alpha).

This is also a primary effect based on Cohen’s (1988) guidelines (Privitera and Mayeaux, 2018). Therefore, this indicates also that there are statistically significant differences between AEFLLs and NBES in terms of the frequency of the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations.

The eta-squared formula is η 2[H]= (H-k+1)/(n-k), where H is the obtained value of the Kruskal-Wallis test in SPSS, k is the size of the corpora and n is the total number of collocations for both the AEFLLs corpora, BAWE corpus and BNC (Tomczak and Tomczak, 2014).

In addition to the Kruskal-Wallis H test, the multiple comparisons indicate that there is no significant difference between the BNC and BAWE in terms of the use of the 20-collocation set. However, the comparison suggests that there is a significant difference between the AEFLLs corpus and both native English corpora, rejecting the null hypothesis at p-value >0.000.

Table 6 below lists 28 collocations with the assigned frequency threshold in BAWE. Like the AEFLLs, ‘very’ is the most frequent adverb occurring 18 times, which accounts for 64.28%. Five of these collocations also occur in the 20 collocations for the AEFLLs. They are ‘very important’, ‘very useful’, ‘very good’, ‘very popular’ and ‘very dangerous’. These five collocations are common in everyday language, in which they are more frequently used by the NBES than AEFLLs, except for ‘very good’ and ‘very dangerous’.

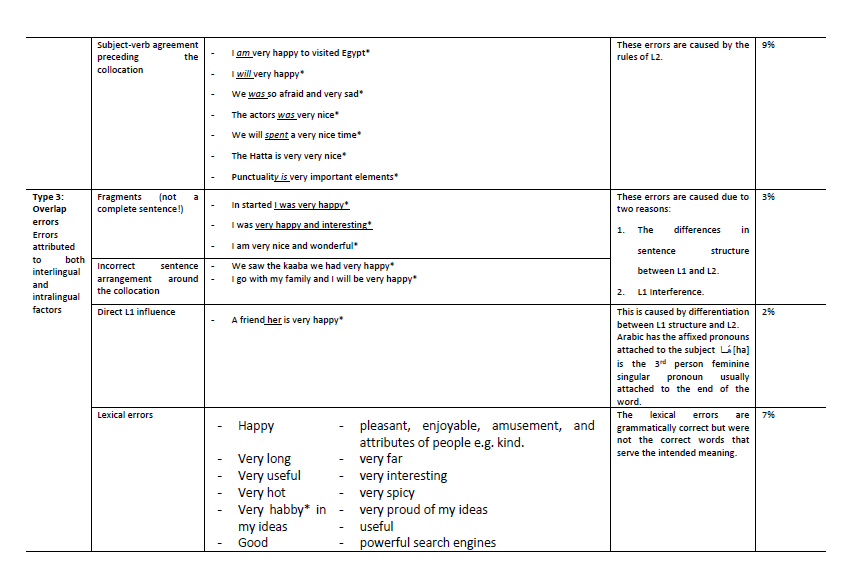

Error analysis results

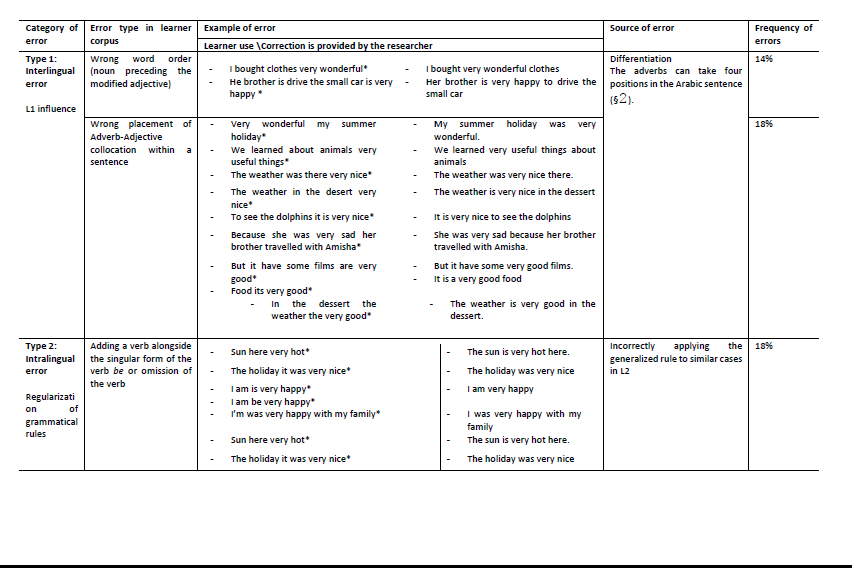

According to the analytical framework of error analysis, the results showed a natural use of the set of 20 collocations in the AEFLLs data. The 20 collocations are grammatically correct as standalone entities. The concordance analysis identified three broad categories of error in the collocation sets which were interlingual errors, intralingual errors, and errors attributed to an interaction between the interlingual and intralingual error classifications to which I refer as overlap errors (see Table 9 in the Appendices). Figure 6 shows the total frequency counts in percentage for each error type. The interlingual errors have the highest frequency of occurrence, followed by intralingual and overlap errors, accounting for 32%, 27%, and 12% respectively.

The first category, interlingual error, is syntactic, seen in the following example of a noun that is modified by an adjective. The noun ‘clothes’ incorrectly precedes the adjective in the sentence ‘I bought clothes very nice’. Adjectives can be attributive or predictive; the adjective in the collocation ‘very nice’ in this example should be attributive, but incorrect usage creates a humorous effect as if the learner is talking to him/herself. The second interlingual error is in the positioning of a collocation in a sentence creating unnatural sentences, such as ‘very wonderful my summer holiday’. This sentence has a clear L1 influence in terms of sentence structure. The two errors shown here could be related to the four possible sentence structures in Arabic.

The second category is intralingual errors which consist mainly of errors that occur around the collocation. One of these is the addition of extra sentence elements preceding a collocation, such as the addition of the verb ‘is’ in the sentence:

- ‘I am is very happy’*

- and the addition of ‘it’ in ‘the holiday it was very nice’*.

The second intralingual error is related to subject-verb agreement. For example, the verb ‘be’ in ‘the actors was very nice’*.

The third category is the overlap error, referred to as such as it includes both interlingual and intralingual factors, mostly contextual errors that occur within the context of the collocation. The errors classified under this type were sentence fragments, incorrect sentence structure around the collocation, direct L1 influence errors and lexical errors. First, sentence fragments were observed in the absence of the modified noun that follows the adjective collocates. To illustrate this, the AEFLLs corpus includes sentences such as ‘I was very happy and interesting’ and ‘I am very nice and wonderful’. The two examples show that learners tend to use these collocations in isolation without completing the intended meaning, creating fragmented sentences. The second error is seen in the arrangement of the sentence structures particularly when using the English relative clauses. For example, there is an error in saying, ’We saw the Kaaba we had very happy’ which should be said as ‘We were very happy when we saw the Kaaba’. This particular sentence structure could be especially difficult, in the same vein as Haza'Al Rdaat and Gardner (2017) who found that conditional clauses are challenging for AEFLLs. The third type is unusual as an apparently direct L1 influence leads to a negative transfer. The error is observed in the position of the pronoun in the example ‘a friend her is very nice’* in which the student used a pronoun after the subject. In Arabic, the affixed pronouns are usually attached at the end of a word, in this case, هَا[ha], the 3rd person feminine singular pronoun. These three subtype errors are related to the word order structure that AEFLLs encounter when using English as a foreign language (Al-Khresheh, 2010; Murad and Khalil, 2015). The last error type under this category is the lexical error. This is mostly associated with the choice of lexical items within the collocation component. This can be seen in cases where some adjectives are better than others in conveying the intended meaning. For instance, the adjective ‘powerful’ is better than ‘good’ in the collocation ‘very good search engine’ (see list of examples is given in Table 9).

DISCUSSION

It is noteworthy to mention some contributory factors to the main differences between the two corpora. The collocation output for the AEFLLs shows that they use certain essential English words more often than others, more than native speakers do. For example, the adverb ‘very’ is used instead of other adverbs where other degree adverbs would be somewhat better in delivering the right meaning. However, some instances do not require the use of ‘very’ which points to a direct L1 interference (e.g. when the learners express their happiness when they are with their family, they tend to exaggerate the feeling by using ‘very’ which is a common adverb in Arabic). The use of ‘very’ is linguistically correct in most cases. However, other adverbs would be more natural/expressive in certain contexts, which is in line with findings by Yilmaz and Dikilitas (2017) that Turkish learners tend to rely on degree adverbs such as ‘very’ and ‘so’. Foreign language learners tend to use a narrow range of words (Appel and Szeib, 2018). Also, this result is in agreement with other studies that have found that EFLLs face difficulty with word choice as they resort to using and repeating some adverbs more than others (Murad and Khalil, 2015; Phuket and Othman, 2015). The learners’ lexical choice errors are a common problem for EFLLs from different L1s; it reveals that their choice is limited as the learners are not familiar with other words that would enable them to communicate more effectively and efficiently (Xu and Liu, 2012). Moreover, the AEFLLs corpus shows the use of generic vocabulary which could be attributed to the topics covered in the corpus. In contrast, the BAWE corpus reveals a more varied use of collocations.

The extraction phase reveals a difference between the two corpora in terms of the number of Adverb-Adjective collocations. The collocation output in IntelliText revealed only 63 and 101 collocations for the AEFLLs corpora and the BAWE corpus respectively. Therefore, I have implemented another extraction method to extract more data for the comparative study by considering the top 100 adverbs in the BNC; these adverbs also occur in the top 100 adverb list in the BAWE corpus. Besides, the data in this study leads to the rejection of the method that investigates instances with a 20 ipmw cut-off frequency as there were only nine collocations with this frequency range in the AEFLLs corpus; most of the collocations listed fall under the 0-5 ipmw cut-off frequency, which accounts for 91.14% of the AEFLLs corpus and 97.76% of the BAWE corpus (see Table 4). According to this result, setting the cut-off frequency to 20 ipmw seems to be an inappropriate approach to implement when investigating the differences between the two data sets. Therefore, I proceeded to investigate the collocations that occurred within the range of 6-150 ipmw, creating a list of 20 collocations (see Table 6.).

The first set of questions aimed to investigate whether there are statistically significant differences between AEFLLs and NBES in terms of the use of Adverb-Adjective lexical collocations. The results suggest that the Adverb-Adjective collocation is not frequently used by AEFLLs. It seems that this collocation set is challenging to EFLLs, which is apparent in the small number of the total instances in the AEFLLs corpus (Demir, 2017). This is in agreement with other scholars who found that EFLLs found that Adverb-Adjective collocations were the most challenging collocation to produce, both for Japanese and French EFLLs (Kurosaki, 2012), and for Arab EFLLs (Farooqui, 2016; Mahmoud, Abdulmoneim., 2005). The single most striking observation to emerge from the data comparison is that the frequency results for the 20 collocations were significantly higher for the AEFLLs corpus than the NBES corpus. This observation contradicts the findings of Demir (2017) who found a statistically significant difference in the opposite direction between native English students and Turkish EFLLs in terms of the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations.

The second research question of this paper aimed to examine L1 interference on the use of Adverb-Adjective collocation. The EA has shown that the collocations sound correct when seen as separate entities yet there were contextual errors that could be attributed to L1 influence, mainly seen in the position of a collocation within a sentence (e.g. ‘We saw the Kaaba we had very happy’*). This finding is consistent with that of (Al-Shormani and Al-Sohbani, 2012) who found that collocations were linguistically well formed. Still, the errors were mainly contextual (e.g. ‘get marriage’ instead of ‘get married’). The EA has shown that there are three types of contextual errors that could be attributed to L1 interference, which were interlingual errors, intralingual errors, and overlap errors. I deliberately named the third type an overlap error as some previous studies refer to this type as bi-source caused by both L1 and L2 (Rostami Abusaeedi and Boroomand, 2015; Tajadini Rabori, 2006). L1 interference for AEFLLs is seen in the first and the third type mainly in the position of the collocation within the sentence, and the position of the noun that should follow the adjective in the collocation set, which usually precedes the adjective in Arabic as in the learners’ attempts. This is related to word order problems that face EFLLs in English writing and speaking (Al-Tamari, 2019; Latupeirissa and Sayd, 2019). Also, the choice of lexical items could be influenced by learners’ L1 (Mahmoud, Abdulmoneim, 2011). The errors in the choice of lexical items are in line with previous studies that found these errors were caused by interlingual factors (Mahmoud, Abdulmoneim, 2011; Shammas, 2013).

The second type is intralingual error, usually caused by the differences between the two languages; the collocation is correct in this type yet what precedes and follows the collocation is incorrect. Subject-verb agreement is also observed in the context around the collocation due to over-generalisation of some English grammatical rules. These include the addition of the verb ‘be’ and incorrect forms of lexical items within the sentence around the collocation. The results of the intralingual types are in line with previous studies of AEFLLs (El-Dakhs, 2015; Sabah, 2015). The third type, the overlap error, is seen in the creation of sentence fragments and incorrect sentence structures that are attributed to or are caused by L1 influence and the over-generalisation of the rules of L2. The overlap error consists of both interlingual and intralingual errors. To clarify this, learners add the article ‘a’ following the English Article system and incorrectly position the pronoun ‘her’ following the L1 rules (e.g. ‘A friend her is very happy’*), thus creating an overlap error with both interlingual and intralingual errors in a single sentence.

IMPLICATIONS FOR LANGUAGE PEDAGOGY AND CONCLUSION

The findings of this study have several important pedagogical implications for future practice. The study provides a new understanding of the positioning of the Adverb-Adjective collocation within the English and Arabic sentence. Therefore, teaching the differences in word order between English and Arabic and using corpora to train AEFLLs to identify the natural word-order of sentences containing Adverb-Adjective collocations would help improve learners’ language proficiency. The observations resulting from this study may also contribute to the teaching of Adverb-Adjective collocations and their position in a sentence among EFLLs more generally. The frequency analysis revealed an interesting result for the set of 20 collocations (see Table 5); I found that these collocations have a higher frequency of occurrence in the AEFLLs corpora than in the native corpus. This result indicates that EFLLs tend to rely on the specific collocations with which they are familiar; for example, they use ‘very’ instead of other adverbs and ‘nice’ instead of other adjectives. Therefore, using corpora to identify possible synonyms for adverbs like ‘very’ and adjectives like ‘nice’ can help learners produce native-like collocations and expressions and avoid literal translations of collocations from their L1. For example, language teachers can use corpus data to create classroom materials and exercises to teach synonyms of ‘very’ and other possible adverbs. Corpora can benefit from??? learning and teaching in terms of observing how some adverbs are more suitable than others. For instance, learners would see that for ‘infectious’ the adverb ‘highly’ is much more common than ‘very’. This is an example of a hands-off approach to corpus-based language learning. Corpus-based language learning could be of immense value to English curriculum designers, as corpus data may form the basis for the development of essential English language learning materials and methods practiced in classrooms, developing strategies to improve three types of contextual errors that could be attributed to L1 interference: interlingual errors (i.e. caused by L1 interference), intralingual errors (i.e. caused by the rules of the second/foreign language learned), and overlap errors. Thus, teachers should consider focusing on L1 interference when creating classroom materials and exercises, whenever this is possible for comparison purposes. L1 interference should be taken as a positive difference because this will allow learners to notice the differences between the structures of the two languages (Hamdallah and Tushyeh, 1993).

Furthermore, this study has demonstrated that AEFLLs tend to rely on using more generic adverbs and adjectives in collocations. Therefore, the focus should be on teaching the possible words that would typically appear with the vocabulary being taught which could enhance language development in terms of understanding definitions and increasing vocabulary stock. From personal experience, foreign language teaching in Arab teaching settings focuses on vocabulary teaching without explaining how to employ vocabulary in context. Some scholars stated that EFL is limited to teaching grammar and overlooks vocabulary teaching (Martyńska, 2004; Newton, 2018). The teaching system mainly considers providing definitions for words and giving synonyms and antonyms, yet they disregard teaching the possible co-occurring words (i.e. collocations). In line with teaching the typical co-occurring words, Hunston and Francis claimed that ‘most words have no meaning in isolation, or at least are very ambiguous’ (2000). Also, this study has shown that Adverb-Adjective collocations are used much less frequently by AEFLLs than by native speakers. This observation demonstrates the necessity to encourage the teaching of Adverb-Adjective collocations, especially as this collocation is absent in Arabic. Furthermore, the study has shown that AEFLLs rarely use adverbs and this observation indicates a need for tutors to place more emphasis on the teaching of different types of adverbs and their use in English (Yilmaz and Dikilitas, 2017).

Grammatical differences between Arabic and English in terms of lexical collocations should be highlighted. There should be a focus on teaching adverbs through a corpus-based approach (e.g. through concordances). This approach is also beneficial for language teachers seeking to create examples for classroom exercises. Referring back to corpus data would be beneficial for having informative and detailed answers to the questions raised by students about collocations (Aijmer, 2009). This study has shown a need to focus on contrastive pairs to improve collocation teaching (e.g. use of the adjectives ‘large’ versus ‘big’).

In this paper, I set out to explore the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations by Arab EFLLs from Kuwait and Dubai, UAE and NBES. I have identified that Arab EFLLs use Adverb-Adjective collocations considerably less than NBES. This observation may indicate that Arabic-speaking EFLLs find Adverb-Adjective collocations particularly challenging and they thus avoid using them; however, more quantitative and qualitative data would need to be analysed in order to further explore the L1 interference on the use of Adverb-Adjective collocations.

For future studies, a larger sample of Adverb-Adjective collocations would need to be collected and analysed to understand the core issues related to Adverb-Adjective collocation by Arabic speaking EFLLs. In addition, a further corpus-based study that focused on degree adverbs such as the adverb ‘very’ jadan جداً could provide further insight into the teaching of Adverb-Adjective collocations to AEFLLs. Thus, teachers should consider creating classroom materials and exercises that consider L1 interference on the use of adverbs. Finally, further comparative studies that utilise a parallel English-Arabic learner corpus would be beneficial to examine the L1 influences behind learners’ choice of lexical items within the Adverb-Adjective collocation.

Address for correspondence: mlrra@leeds.ac.uk / Rrm.alshammari@hotmail/gmail.com

References

Abd Ai-Qadir, M. 2015. "Voice'S Collocations, and Its Role in "Coherence" in The Narrative Text: (Ghadah Al-Samman, S" Beirut 75"). Tishreen University Journal for Research and Scientific Studies- Arts and Humanities Series. 37(2), pp.112-129.

Abushihab, I., El-Omari, A.H. and Tobat, M. 2011. An Analysis of Written Grammatical Errors of Arab Learners of English as a Foreign Language at Alzaytoonah Private University of Jordan. European Journal of Social Sciences. 20(4), pp.543-552.

Ädel, A. and Erman, B. 2012. Recurrent word combinations in academic writing by native and non-native speakers of English: A lexical bundles approach. English for Specific Purposes. 31(2), pp.81-92.

Aijmer, K. 2009. Corpora and language teaching. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Al Aqad, M. 2013. Syntactic Analysis of Arabic Adverb’s between Arabic and English: X Bar Theory. International Journal of Language and Linguistics. 1(3), pp.70-74.

Al-Khresheh, M. 2010. Interlingual interference in the English language word order structure of Jordanian EFL learners. European Journal of Social Sciences. 16(1), pp.105-113.

Al-Shormani, M.Q. and Al-Sohbani, Y.A. 2012. Semantic errors committed by Yemeni university learners: Classifications and sources. International Journal of English Linguistics. 2(6), pp.120-139.

Al-Tamari, E.A. 2019. Analyzing Speaking Errors Made by EFL Saudi University Students. Arab World English Journal. Special Issue (The Dynamics of EFL in Saudi Arabia.), pp.56 -69.

Al-Zahrani, M. 1998. Knowledge of English lexical collocations among male Saudi college students majoring in English at a Saudi university. Doctoral dissertation thesis, Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Alanazi, M. 2017. On the Production of Synonyms by Arabic-Speaking EFL Learners. International Journal of English Linguistics. 7(3), pp.17-28.

Alangari, M.A. 2019. A corpus-based study of verb-noun collocations and verb complementation clause structures in the writing of advanced Saudi learners of English. thesis, University of Reading.

Aldera, A.S. 2016. Cohesion in Written Discourse: A Case Study of Arab EFL Students. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ). 7(2), pp.328-341.

Alharbi, R.M. 2017. Acquisition of Lexical Collocation: A corpus-assisted contrastive analysis and translation approach. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Newcastle University.

Alsied, S.M., Ibrahim, N.W. and Pathan, M.M. 2018. Errors Analysis of Libyan EFL Learners' Written Essays at Sebha University. International Journal of Language and Applied Linguistics. 3(1), pp.1-32.

Appel, R. and Szeib, A. 2018. Linking adverbials in L2 English academic writing: L1-related differences. System. 78, pp.115-129.

Auer, P. 1997. Co-occurrence restrictions between linguistic variables. Variation, change, and phonological theory. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company pp.69-100.

Bahns, J. 1993. Lexical collocations: a contrastive view. ELT Journal. 47(1), pp.56-63.

Bahns, J. and Eldaw, M. 1993. Should we teach EFL students collocations? System. 21(1), pp.101-114.

Bahumaid, S. 2006. Collocation in English-Arabic translation. Babel. 52(2), pp.133-152.

Bartsch, S. 2004. Structural and functional properties of collocations in English: A corpus study of lexical and pragmatic constraints on lexical co-occurrence. Germany: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Basal, A. 2017. Learning collocations: Effects of online tools on teaching English adjective‐noun collocations. British Journal of Educational Technology. 50(1), pp.342-356.

Biber, D. and Barbieri, F. 2007. Lexical bundles in university spoken and written registers. English for Specific Purposes. 26(3), pp.263-286.

Biber, D., Conrad, S. and Cortes, V. 2004. If you look at . . . : Lexical Bundles in University Teaching and Textbooks. Applied Linguistics. 25(3), pp.371-405.

Brashi, A.S. 2005. Arabic collocations: implications for translations. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of Western Sydney.

Chang, Y. 2018. Features of Lexical Collocations in L2 Writing: A Case of Korean Adult Learners of English. English Teaching. 73(2), pp.3-36.

Chen, Y.-H. and Baker, P. 2010. Lexical bundles in L1 and L2 academic writing. Language Learning & Technology. 14(2), pp.30-49.

Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Second Edition. ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Corder, S.P. 1967. The significance of learner's errors. IRAL-International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. 5(1-4), pp.161-170.

Demir, C.n. 2017. Lexical Collocations in English: A Comparative Study of Native and Non-native Scholars of English. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies. 13(1), pp.75-87.

Diab, N. 1997. The transfer of Arabic in the English writings of Lebanese students. The ESPecialist. 18(1), pp.71-83.

Durrant, P. and Schmitt, N. 2010. Adult learners’ retention of collocations from exposure. Second language research. 26(2), pp.163-188.

El-Dakhs, D.A.S. 2015. The lexical collocational competence of Arab undergraduate EFL learners. International Journal of English Linguistics. 5(5), pp.60-74.

Evison, J. 2010. What are the basics of analysing a corpus. The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics. New York.: Routledge, pp.122-135.

Farooqui, A.S. 2016. A Corpus-Based Study of Academic-Collocation Use and Patterns in Postgraduate Computer Science Students' Writing. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of Essex.

Farrokh, P. 2012. Raising awareness of collocation in ESL/EFL classrooms. Journal of Studies in Education. 2(3), pp.55-74.

Firth, J.R. 1957. Papers in linguistics 1934-1951. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Gass, S.M. and Selinker, L. 2008. Second Language Acquisition: An Introductory Course. Third edition. ed. New York and London: Routledge.

Ghazala, H. 1993. Translating Collocations: Arabic-English (in Arabic). Turjuman.

Gilquin, G.t. 2005. From design to collection of learner corpora. In: Granger., S., et al. eds. The Cambridge Handbook of Learner Corpus Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press., pp.1-27.

Granger, S. 2003. The international corpus of learner English: a new resource for foreign language learning and teaching and second language acquisition research. Tesol Quarterly. 37(3), pp.538-546.

Gries, S. 2013. Corpus Linguistics: Quantitative Methods. In: Chapelle, C. ed. The Encyclopaedia of Applied Linguistics. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Hago, O.E. and Ali, M.H. 2015. Assessing English Syntactic Structures Experienced by Sudanese Female Students at Secondary Schools, (2013-2014). Arab World English Journal (AWEJ). 6(2), pp.213-241.

Hamdallah, R. and Tushyeh, H. 1993. A contrastive analysis of selected English and Arabic prepositions with pedagogical implications. Papers and Studies in Contrastive Linguistics. 28(2), pp.181-190.

Hashim, A. 2017. Crosslinguistic influence in the written English of Malay undergraduates. Journal of Modern languages. 12(1), pp.60-76.

Haza'Al Rdaat, S. and Gardner, S. 2017. An analysis of use of conditional sentences by Arab students of English. Advances in Language and Literary Studies. 8(2), pp.1-13.

Henriksen, B. 2013. Research on L2 learners’ collocational competence and development–a progress report. C. Bardel, C. Lindqvist, & B. Laufer (Eds.) L. 2, pp.29-56.

Hunston, S. 2002. Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hunston, S. and Francis, G. 2000. Pattern grammar: A corpus-driven approach to the lexical grammar of English. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Husamaddin, K. 1985. Idiomatic Expressions. Cairo: Maktabat Al-Anjilu Al-Masriyah.

Izwaini, S. 2016. The translation of Arabic lexical collocations. Translation and Interpreting Studies. 11(2), pp.306-328.

Kennedy, G. 2014. An introduction to corpus linguistics. New York: Routledge.

Khansir, A.A. 2012. Error Analysis and Second Language Acquisition. Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 2(5), pp.1027-1032.

Khoja, H.Y.Y. 2019. Exploring the Use of Collocation in the Writing of Foundation-Year Students at King Abdulaziz University. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, The University of Leeds.

Kruskal-Wallis H Test using SPSS Statistics. n.d. [Online]. [Accessed 25 February]. Available from: https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/kruskal-wallis-h-test-using-spss-statistics.php

Kurosaki, S. 2012. An analysis of the knowledge and use of English collocations by French and Japanese learners. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, University of London Institute in Paris.

Lado, R. 1957. Linguistics across cultures. MI: University of Michigan Press.

Latupeirissa, D.S. and Sayd, A.I. 2019. Grammatical errors of writing in EFL class. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture. 5(2), pp.1-12.

Laufer, B. and Waldman, T. 2011. Verb‐Noun Collocations in Second Language Writing: A Corpus Analysis of Learners' English. Language Learning. 61(2), pp.647-672.

Leech, G. 1992. Corpora and theories of linguistic performance. In: Svartvik, J. ed. Directions in corpus linguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter., pp.105-122.

Lennon, P. 1991. Error: Some problems of definition, identification, and distinction. Applied Linguistics. 12(2), pp.180-196.

MacArthur, F. and Littlemore, J. 2008. A discovery approach to figurative language learning with the use of corpora. In: Boers, F. and Lindstromberg, S. eds. Cognitive linguistic approaches to teaching vocabulary and phraseology., pp.159-188.

Mahmoud, A. 2005. Collocation errors made by Arab learners of English. Asian EFL Journal. 5(2), pp.117–126.

Mahmoud, A. 2011. The role of interlingual and intralingual transfer in learner-centered EFL vocabulary instruction. Arab World English Journal. 2(3), pp.28-47.

Manning, C.D., Manning, C.D. and Schütze, H. 1999. Foundations of statistical natural language processing. MIT press.

Martinez, R. and Schmitt, N. 2012. A phrasal expressions list. Applied Linguistics. 33(3), pp.299-320.

Martyńska, M. 2004. Do English language learners know collocations? Investigationes linguisticae. 11, pp.1-12.

McEnery, T. and Hardie, A. 2011. Corpus linguistics: Method, theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McEnery, T. and Hardie, A. 2012. Corpus Linguistics: Method, theory and practice. [Online]. [Accessed 16 January 2020]. Available from: http://corpora.lancs.ac.uk/clmtp/2-stat.php

McEnery, T. and Hardie, A. 2013. The History of Corpus Linguistics. In: Allan, K. ed. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics.

McEnery, T., Xiao, R. and Tono, Y. 2006. Corpus-based language studies: An advanced resource book. Routledge.

Mel’čuk, I. 1998. Collocations and lexical functions. Phraseology. Theory, analysis, and applications. pp.23-53.

Murad, T.M. and Khalil, M.H. 2015. Analysis of Errors in English Writings Committed by Arab First-year College Students of EFL in Israel. Journal of Language Teaching and Research. 6(3), pp.475-481.

Mustafa, B.A. 2010. Collocation in English and Arabic: A Linguistic and Cultural Analysis. Journal of the College of Basic Education. 15(65), pp.29-43.

Nesselhauf, N. 2003. The use of collocations by advanced learners of English and some implications for teaching. Applied Linguistics. 24(2), pp.223-242.

Newton, J. 2018. Teachers as learners: The impact of teachers’ morphological awareness on vocabulary instruction. Education Sciences. 8(4), p161.

Nugroho, A. 2015. Students’ Knowledge and Production of English Lexical Collocations. Journal of English Language and Culture. 5(2), pp.87-106.

Phoocharoensil, S. 2013. Cross-Linguistic Influence: Its Impact on L2 English Collocation Production. English Language Teaching. 6(1), pp.1-10.

Phuket, P.R.N. and Othman, N.B. 2015. Understanding EFL Students' Errors in Writing. Journal of Education and Practice. 6(32), pp.99-106.

Privitera, G.J. and Mayeaux, D.J. 2018. Core Statistical Concepts With Excel®: An Interactive Modular Approach. California: SAGE Publications.

Rabeh, F. 2010. Problems in Translating collocations - The Case of Master I Students of Applied Languages. Master degree in Applied Language Studies thesis, Mentouri University-Constantine.

Rajab , A.S., Darus, S. and Aladdin, A. 2016. An investigation of Semantic Interlingual Errors in the Writing of Libyan English as Foreign Language Learners. Arab World English Journal. 7(4), pp.277- 296.

Regan, V. 1998. Sociolinguistics and language learning in a study abroad context. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad. 4(3), pp.61-91.

Richards, J.C. 1971. A non-contrastive approach to error analysis. English Language Teaching Journal. 25, pp.204-219.

Rostami Abusaeedi, A.A. and Boroomand, F. 2015. A quantitative analysis of Iranian EFL learners' sources of written errors. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning. 4(1), pp.31-42.

Sabah, S.S. 2015. Negative Transfer: Arabic Language Interference to Learning English. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ). 4(Special Issue on Translation), pp.269-288.

Shammas, N.A. 2013. Collocation in English: Comprehension and Use by MA Students at Arab Universities. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 3(9), pp.107-122.

Siyanova, A. and Schmitt, N. 2008. L2 Learner Production and Processing of Collocation: A Multi-study Perspective. The Canadian Modern Language Review. 64(3), pp.429-458.

Tahseldar, M., Kanso, S. and Sabra, Y. 2018. The Effect of Interlanguage and Arabic Verb System on Producing Present Perfect by EFL Learners. International Journal of New Technology and Research. 4(8), pp.53-65.

Tajadini Rabori, M. 2006. “Error Detection” as a Device towards the Investigation and Elaboration of Interlanguage. Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities of Shiraz University. 23(1), pp.91-106.

Tomczak, M. and Tomczak, E. 2014. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends in Sport Science. 1(21), pp.19-25.

Xu, Y. and Liu, Y. 2012. The Use of Adverbial Conjuncts of Chinese EFL Learners and Native Speakers--Corpus-based Study. Theory & Practice in Language Studies. 2(11), pp.2316-2321.

Yilmaz, E. and Dikilitas, K. 2017. EFL Learners' Uses of Adverbs in Argumentative Essays. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language). 11(1), pp.69-87.

Appendices

Appendix I

Appendix II

[1] Mean Rank values represent the median rank (a default error by the statistical package).