A Needs Analysis of the Assessed Writing Genres of a 2nd Year Transnational Undergraduate Engineering Programme

Matthew Ketteringham

Language Centre, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies, University of Leeds

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research was to carry out a needs analysis (NA) of the assessed writing genres on a second-year transnational education (TNE) undergraduate engineering programme. A case study approach was used to gain a deeper understanding of the writing requirements of second year engineers and to inform course design on an English for Specific Academic Purposes (ESAP) insessional writing module. The methodology used to carry out the NA included genre analysis of institutional artefacts, interviews with faculty, and a student questionnaire. Based on Nesi and Gardner’s (2012) thirteen genre classification of the British Academic Written English (BAWE) corpus, the results of the analysis highlighted eight writing genres used for assessed coursework. The Exercise genre was found the most, with the use of the Narrative genre through reflection as the third most common genre. The Narrative Genre, Design Specification and Exercise were the only genres found across all four disciplines highlighting the importance of specificity in ESAP provision. The results of faculty interviews and the student questionnaire both found writing was perceived as especially important for engineers. However, some faculty expressed that the students found critical analysis and argumentation difficult. Genre expectations are mostly expressed through structured assignments and marking rubrics, but only explicitly taught in one module. This is mostly reflected by students, although some highlighted the need for independent study or reference to past writing instruction outside engineering when interpreting assessment tasks. This case study has highlighted areas to develop for insessional support, particularly the need for writing instruction on a variety of assessed writing genres across the programme at all levels.

KEYWORDS: ESP, TNE, Needs Analysis, Genre Analysis, Reflection

INTRODUCTION

English for Specific Academic Purposes (ESAP) targets a group of learners from the same discipline and concentrates on discipline-specific communication and language use (Richards and Schmidt, 2002; Anthony, 2019). To address these discipline specific needs, ESAP courses should be designed around students’ needs, and a key tool in understanding these needs is a detailed Needs Analysis (NA). However, Serafini et al. (2015) and Woodrow (2018) report inadequate analysis of student needs when designing courses due to methodological issues or instructor inexperience. These inadequacies may in turn impact student learning through flawed ESAP course design (Du and Shi, 2018).

The ‘single most defining feature’ of ESAP course design is that they are developed from the analysis of learner needs (Woodrow, 2018, p.5). NA as defined by Brown (2016, p.4) is ‘the systematic collection and analysis of all information necessary for defining and validating a defensible curriculum’. NA is a broad term which is primarily based on the analysis of all stakeholder needs, not just the learners, in a particular localised context and often includes other analysis such as discourse, corpus, and genre analysis (Chambers, 1980; West, 1994). The localised context in this study is a new ESAP insessional writing module to support undergraduate engineering students studying at the Southwest Jiaotong – Leeds Joint School. This transnational education (TNE) programme uses English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) and enrols students located in Chengdu, China, on University of Leeds Engineering degrees. Davies et al (2020) state that well designed English for Academic Purposes (EAP) support needs to be provided to learners studying in an EMI context, and that this is particularly true in a TNE programme where students are adapting to new academic expectations and the academic literacies needed to meet them.

The aim of this research is to conduct a NA of a second year TNE undergraduate engineering programme and the results of the study will directly inform course design on the ESAP insessional module described above. The case study aims to create a taxonomy of student writing tasks based on Nesi and Garner’s (2012) Genre Family Classification by analysing the assessment instructions given to students. Then, the views of engineering faculty on disciplinary expectations for these genres are compared with students’ current understanding of these genres. This study therefore continues an established EAP tradition of investigating written genres (Swales, 1990; Nesi and Gardner, 2012) to help students better understand how to communicate as a member of their chosen discourse community (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Hyland and Hamp-Lyons, 2002; Hyland 2018).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Needs analysis

The systematic investigation of needs requires the collection and analysis of the necessary data to conduct the assessment of these needs (Bocanegra-Valle, 2016). Wilkins (1976) states that defining objectives is the first step in course design. These objectives should be based on the analysis of the communicative needs of the learner (cited in West, 1994, p.2). These needs are ‘determined by the demands of the target situation, that is, what the learner has to know in order to function effectively in the target situation’ (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987, p.55). This part of the analysis is more commonly known as the ‘Target Situation Analysis’ (TSA) (Dudley-Evans & St. John, 1998, p.123). The TSA is seen as the end product, which is compared with a ‘Present Situation Analysis’ (PSA) that analyses what the learners currently know or ‘lack’ (Richterich and Chanercel, 1980 cited in Songhori, 2008). Finally, the local teaching context and external factors relevant to learning should be considered. Holliday (1994) termed this ‘means analysis’. These early approaches to NA have evolved and are interwoven but they are still central to traditional NA, although critical and ethnographic approaches may now also be considered (Bocanegra-Valle, 2016). This section discussed the key investigations that may be considered in a NA, and the following section discusses how the communicative writing needs of the students are determined.

Genre analysis

Genre is a central concept in ESAP course design because these genres relate to the ‘target contexts’ that students wish to study (Hyon, 2018, p.4). Swales (1990) describes genres as ‘communicative events’ that are constructed for a particular discourse community and are composed of patterns of ‘structure, style, content and intended audience’ (p.58). Therefore, genre analysis can be used as a framework to help students understand and produce what is expected of them in their chosen discipline. Genre analysis may be done in a number of ways. Firstly, it can be conducted by collecting the genres students may have to produce within the target discipline, for example research reports or case studies (Woodrow, 2018), and secondly, by structural move analysis to see how these genres are organised. Swales’ (1990) influential ‘creating a research space’ (CARS) model is an early example of move analysis that has influenced ESAP research. Finally, it can be conducted by identifying lexicogrammatical features such as the use of hedges and personal pronouns (Hyon, 2018).

Needs analysis of academic writing

Genre in EAP has mainly focussed on written texts to identify the variation of genres across disciplines, and to analyse similarities and differences between genres, within and across different disciplines. (Horowitz, 1986; Leki and Carson, 1994; 1997; Hyon, 1996; Zhu, 2004b; Gimenez, 2008; Hyland, 2009; Hyland and Tse, 2009; Nesi and Gardner, 2012). However, one criticism is by offering texts as rigid forms that can be taught prescriptively, we are ignoring the social and cultural context of how the texts are formed. The concept of discourses as communities (Swales, 1990) has been explored to address this argument. By focusing on specific genres written by an insider of a discourse community, of which a student wishes to earn membership, students can explicitly see what is required to communicate within that community (Lave and Wenger, 1991). Moreover, to learn this ‘new way of knowing’ students need to develop their academic literacy (Lea and Street, 1998, p.157).

Research on academic writing has increased as a response to this understanding that students need a disciplinespecific specialised literacy. This research has highlighted the ‘sociocultural dimension of academic writing’ and that disciplines are governed by a shared communicative purpose of knowledge creation (Swales, 1990; Berkenkotter and Huckin, 1995 cited in Zhu, 2004a, p.29; Hyland, 2000; Wardle, 2009). A large amount of research has been done on academic genres, including genre text types, structures, and features within genres. The research shows variation of genres between and across academic disciplines and this variation highlights the difference in values and beliefs in academic communities (Conrad, 1996; Hyland, 1997; Chang and Swales, 1999 cited in Zhu, 2004a; Peacock, 2002; Hyland, 2009). However, there are some criticisms that genre analysis exposes students to texts written by accomplished writers or 'experts', and not texts that they themselves will be asked to produce (Paltridge, 2004). Consequently, research on genre families of student writing has been carried out to identify the writing tasks students need to complete in higher education. An early study by Horowitz (1986) identified seven categories of writing genres across seventeen departments at an American university. A more recent and comprehensive study was carried out by Nesi and Gardner (2012) which was based on the analysis of the British Academic Written English (BAWE) corpus of student writing. Their study highlighted thirteen genre families which were used to classify genres in this study (see Appendix 1). They believe these genres are applicable to all university contexts; however, they do concede that further investigation of disciplinary contexts may reveal genres not identified, and genres of the same name may have different linguistic features in different disciplines.

Further research has been carried out on student writing tasks at both the undergraduate and graduate level. Some studies concentrated on genres across a wide range of disciplines (Braine, 1995; Hale et al., 1996; Nesi and Gardner, 2006; Cooper and Bikowski, 2007; Gardner, 2008; Gillet and Hammond, 2009; Gardner et al., 2019). While other research has been carried out on student writing in a particular discipline and these include: Zhu (2004b), who investigated assignment types within a business course and what skills were required to complete them; Gimenez (2008), who investigated discipline writing in Nursing and Midwifery and the difficulties students faced writing these genres; and Webster (2021), who investigated the written discourse of digital media studies and found five separate genre families. Student writing in the sciences has concentrated on: Jackson et al., (2006), who found the laboratory report as the most important genre for undergraduate students at a South African university; Rahman et al., (2009), who investigated genre to create an ESAP postgraduate writing course for Science and Technology students in Malaysia; Parkinson (2017), who carried out a genre analysis of student laboratory reports in Science and Engineering; and Doody and Artemeva (2021), who investigated the multimodal nature of student writing in Medical Physics. Little research has been carried out on student writing within Engineering. The research that has been carried out tends to focus on corpus analysis and the development of engineering word lists (Ward, 2009; Shamsudin et al., 2013; Hsu, 2014) or analysis of an engineering insessional writing coursebook (Bozdogan, and Kasap, 2019). Therefore, this study attempts to address this gap by analysing the writing genres in a second year engineering programme and combining this with analysis of both faculty and student views on academic writing, and how these views contrast.

Previous studies have been undertaken by analysing students’ writing needs from different perspectives: tutor expectations (Vardi, 2000; Zhu, 2004a; Nesi and Gardner, 2006); and students’ understanding and perception of writing needs (Leki and Carson, 1994; Asaoka and Usui, 2003; Wu and Lou, 2018). One possible weakness of these studies is the lack of cross-analysis between faculty and students. However, one study contrasted the views of both tutors and students (Bacha and Bahous, 2008), but this was based more on the perception of language proficiency, rather than taking what Lea (2004) terms an academic literacies approach of analysing the differences between faculty and students’ understanding of the writing process, and what is required for a particular genre. This study aims to identify these differences and as a result improve the teaching and learning on an ESAP insessional writing module. The next section discusses the research methodology used for the NA and how the data was collected and analysed.

METHODOLOGY

This research uses a case study approach with the collection of institutional artefacts, and qualitative data from interviews with faculty and a student questionnaire to conduct a NA of a second-year engineering degree programme. A case study approach was chosen as case studies are characterised by an in-depth study of one setting (Denscombe, 2014). The following research questions were investigated:

- What are the assessed writing genres across year two of an undergraduate engineering programme?

- What are the disciplinary expectations for these genres and how are these expressed?

- What are the students’ prior knowledge & experience of these genres?

Context and participants

The research was conducted in a TNE joint engineering school and the school offers engineering degrees in Civil Engineering (CE), Computer Science (CS), Mechanical Engineering (ME), and Electronic and Electrical Engineering (EE). Initially, the Head of School for each programme was approached to ask for permission to speak to Module Leaders and access assessment information via the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). In total, 34 Module Leaders were emailed with positive responses from 22 (65%). Two Module Leaders from each school (CE, CS, ME, EE) were invited to interview and all eight responded positively. The Module Leaders were all specialists in their subject area with PhDs, and most with industry experience.

The students in the study were close to completing their first year of undergraduate study in one of the schools highlighted above. The students ages ranged from 18 to 22 and most had been studying English for over 10 years, with the past two years within an EMI engineering context. Initially, all 281 year-one students across the four schools were invited to take part in a focus group, but only six responded. Consequently, a questionnaire was sent to all students, with 72 (26%) responses in total. The students or ‘in-service learners’ were included as they are useful sources of information (Long, 2005, p.20) and should be aware of some of the meta-language used to describe academic writing as they have completed a Foundation Year before entering their disciplines.

Data collection instruments

The collection of institutional artefacts was used to answer research question one and involved accessing and analysing assessment instructions, guidance notes and marking criteria to identify the writing tasks the students had to complete. Access was gained to 38 out of 55 (69%) assessments. The remaining 17 (31%) were classified from the Module Handbooks that are given to students. The second instrument used to answer research question two were interviews of faculty. Qualitative interviews were used with a main question and follow-up semi structured interview design. This takes a naturalist paradigm and ‘interpretive constructionism’ approach to research which aims to understand the interviewees’ views and interpretations of the context under study (Rubin and Rubin, 2012). The main questions were based on the aims of the study to investigate the faculty's view on the importance of writing in Engineering, their view on the faculty’s role in helping students develop academic writing skills, and to discuss the genre expectations for one of their assessments. A core set of six questions were asked with the only change dependant on which assessment was being discussed. Follow-up questions were asked if necessary. The interviews were conducted on Microsoft Teams and lasted between 18 and 37 minutes. The interviews were transcribed, and member checked for accuracy. Finally, a questionnaire was used to answer research question three and analyse students’ prior experience of writing in engineering. Questionnaires can provide information on the language attitude and abilities of a given population (Codó, 2008). Students were asked comparable questions to faculty on the importance of writing in Engineering, who they think should be responsible for teaching writing in engineering, and genre expectations for each of the genres found in their relevant discipline. The anonymous 20 question questionnaire was administered through Microsoft Forms and the average time taken to complete the survey was 13 minutes. Triangulation of both methods (interviews, document analysis, and surveys) and sources (students, course artefacts, and faculty) was used to increase the reliability of data analysis (Long, 2005; Serafini et al., 2015).

Data analysis

First, examinations and assessed coursework were divided using the module syllabus. The exams and non-written coursework were removed from the analysis. Then the assessed coursework instructions, guidance and marking criteria were analysed and coded into 13 genre families based on Nesi and Gardner’s (2012) classification. The majority of the instructions had clear descriptions of the task and included marking criteria. One possible weakness of only analysing the instructions without student examples is that the genre may not be clear from the prompt and the ‘faculty member or course developers’ genre expectations may differ (Nesi and Gardner, 2012, p.7). To overcome this, faculties’ genre expectations were included in the research design to check the assessment was correctly categorized and access to the completed student assessment was available if required. However, this was not needed and the assessment instructions, as Wingate (2018, p. 352) notes, are often the only ‘explicit advice’ students receive on how to write coursework genres. Next, the interviews and questionnaire responses were coded around the themes from the questions and other ‘Examples, Events and Topical Markers, and Concepts and Themes’ were applied and analysed across the eight interview and questionnaire responses (Cohen et al., 2011, p.565; Rubin and Rubin, 2012, p.193). Responses were analysed for similarities and differences across and between faculty and student responses.

Research ethics

Institutional ethical approval was granted for this research and informed consent was obtained from all participants through a detailed participant information sheet. All responses were anonymised, and all data was held securely. As I was a colleague of the Module Leads, and the teacher of the student participants, ethical issues surrounding these relationships were considered, particularly ‘free consent’ (Hammersley and Traianou, 2012). However, no institutional authority was exercised, and students' responses were completely anonymous. All faculty approached for an interview accepted with the implicit understanding the results would inform course design on a ESAP module which may impact student learning on their modules.

RESULTS

Results of the Genre Analysis

The following section details the results from the genre analysis to form part of the NA in response to research question one:

- What are the assessed writing genres across year two of an undergraduate engineering programme?

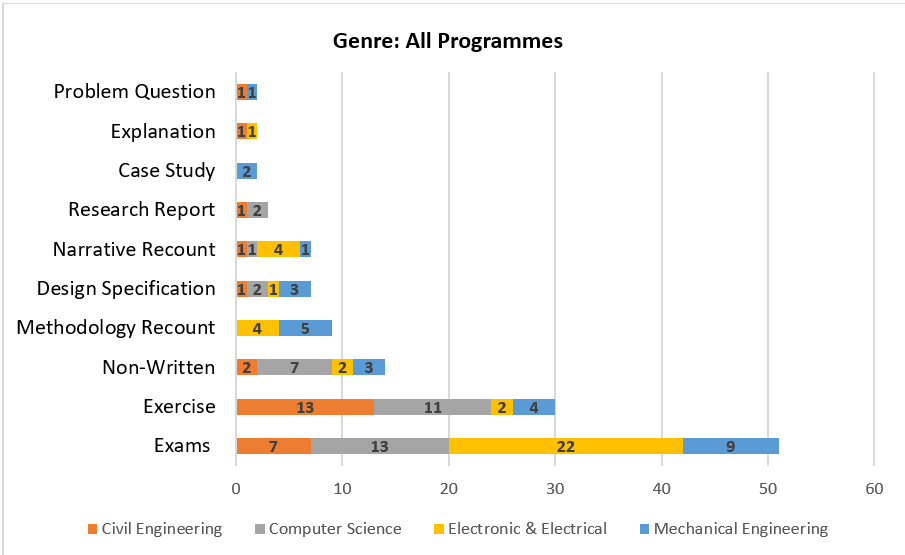

117 assessments in total were found across the four programmes and 106 were written assessments. 51 of these were exams and a total of 55 were assessed written coursework. Within these 55 writing assignments, eight of Nesi and Gardner’s (2012) genre classes were identified (see Figure 1 below): Exercise, Methodology Recount, Narrative Recount, Design Specification, Case Study, Explanation, Problem Question. For an overview of the Nesi and Gardner’s (2012) Genre Classifications see Appendix 1.

The Narrative Recount was the joint third most common genre and at least one Narrative Recount was found in each degree programme. The only other genres found across all programmes were the Design Specification and Exercise. Also, perhaps indicative of year two study, Nesi and Gardner’s (2012, p.170) ‘Preparing for Professional Practice’ genres, specifically the Design Specification was prominent across all four degree programmes. The Methodology Recount was only found in Electronic & Electrical Engineering and Mechanical Engineering. However, assessed laboratory work was also classified as Exercise in some instances with just the experimental data required rather than a full report for submission. Also, through informal discussion laboratory reports are found in other degree programmes but they are not assessed. Finally, the Research Report was only found in Computer Science and Civil Engineering, and the Case Study was only found in Mechanical Engineering.

Results of the faculty interviews

The following section details the results from the faculty semi-structured interviews to form part of the NA in response to research question two:

- What are the disciplinary expectations for these genres and how are these expressed?

Figure 1: Genre classifications found across all four programmes

Figure 1: Genre classifications found across all four programmes

The view of English within the discipline

The first interview question explored the importance of English in the faculty members' course, their engineering field, and also whether English plays a role when grading coursework. All faculty agreed that English was important both in their course and within the profession of engineering. Reference to future careers was mentioned by two faculty members:

It is important and when students begin engineering, they think they will spend all day doing maths […] but as you move through the industry you do lots of report writing, managing projects, letters. Communication is essential. The people who rise to the top in industry are not the ones strong in maths but the communicators. (CE2)

It is critically important. Documentation in industry is just as essential as it was years ago. […] We need to get this through to our students. Their English language needs to be refined if they want to work in industry. (EE1)

However, when discussing the role of English when evaluating student work responses differed. One participant in CS noted ‘I think it is secondary to technical skills,’ and communication, ‘as long I can understand the student’ (ME2), over accuracy, was mentioned on numerous occasions:

We are accredited by the JBM and that is one of their core objectives that we cover that [communication] in our course. (CE2)

This is a really good question, as I think this is changing. If you went back 20 years, it would be of a higher requirement. We still have marking rubrics which feature spelling etc, but it is only found in the Level Three Final Project. So, the quality of written English is not considered to be that significant. We are becoming more inclusive...We have kept it due to accreditation. […] Technical communication is a learning outcome but not writing accuracy. (EE2)

Explanation more than grammatical expression’ [is more important]. (CS1)

Thus, although it is considered important, only two faculty members stated writing accuracy was graded. Interestingly, the first comment below is from an Economics faculty member teaching an interdisciplinary module in Mechanical Engineering:

Yes, extremely important. From Year One this is emphasised right from the beginning and is part of the marking criteria [In Economics]. Academic writing skill and critical review is important’.[…] but not included in the marking criteria’ [In Mechanical Engineering]. (ME1)

English is part of the marking criteria. If the report is 100% the language is 10%. […] Even though the writing is only 10% if it is rubbish it will drag the mark down. (CE1)

Mostly, language is combined with ‘Presentation’ to include other criteria, (EE1) states ‘Presentation is classed as 10%, so not just language.’ However, it was noted that language is important in the final year report:

MK: Does English play a role in evaluating students?

EE1: Not hugely. Only in our final year reports.

This perhaps presents a gap in experience with (CS1) stating ‘A lot of students don’t appreciate the importance of writing and they often stumble in the final year project’ and (CS2) notes ‘At Level One they are just doing programming. In the final year, they write the full report, and it is the first of its kind’.

The transnational education context

The second question focussed on how or if the transnational education context has affected how the modules are taught or assessed. All faculty expressed that the TNE context had not influenced what is taught or how it is assessed to a large degree:

Very little particularly due to covid. Almost exactly the same. (CS1)

The degrees are accredited, so the content is the same. (CE1)

However, subtle changes have occurred to adapt to the local context:

In subtle ways, but the effect has been light. Embarking on the Joint School has made us reflect on how we do things. For example, cultural terminology. (EE2)

Changed lots of examples to Chinese examples. UK specific transport to a local context. (CE1)

But we have tweaked some of the content by adding more local context examples. (ME1)

Also, one member of faculty noted a change in teaching style:

The only difference is perhaps I created vocabulary sheets and I also deliver my lectures slower, and I am more careful with colloquialisms. (EE1)

Finally, one faculty member noted a more structured approach was now taken which will be revisited in the Disciplinary Expectations of the Genres Identified in Research Question One section below:

Scaled back the assessment and much more structured approach. (CS2)

Faculty role in learning how to write within the discipline

The next question considered how students know how to write a particular genre when given an assessment, how it is taught, and whose responsibility is it to teach students how to write as engineers. All eight faculty members stated that students were given a clear assessment brief, with a clear structure to follow, and a marking rubric. Also, there were often lessons to explain what is expected:

[I have] One session on how to use the programme [used in the assessment]. Specific brief on what students need to do. […] Clear structure and rubric given. (CE1)

They are not tutored but the brief has a structure and is detailed with each mark. (CE2)

Clear criteria and I have a separate Q & A session. (ME1)

Clear guidelines and rubrics. (EE1)

However, only one faculty member explicitly tries to teach students how to write:

Writing is explicitly taught. This was taught to both cohorts. (CS2)

One faculty member discussed the use of exemplars/models:

Students are given examples, [this is the] same for all students. (EE2)

Also, it was mentioned by one faculty member that students do get support on their final year project discussed above in The View of English Within the Discipline:

Students are given support for their final year reports. (EE1)

There appeared to be an assumption that at year-two students should already be able to write within their discipline:

Learning through experience across the years. (CS1)

The early years are critical in building their writing skills. (EE1)

Students are already at Level Two and have been taught for two years so they should have developed some academic writing skills. (CE1)

However, faculty were very aware this may not be the case:

Somehow the students are expected to express what they know in a technical fluid way. (CS2)

You are assessing students on knowledge you think they already have. However, they may not due to cultural or other issues. […] From the outset we don’t often give an example. This perhaps highlights a deficient and we make assumptions. Perhaps this is about the buzz phrase the ‘hidden curriculum’. We make assumptions about students’ basic terminology, and we put in the assessments questions we expect students to know what we mean by them. (EE2).

They have not really done lengthy reports. (ME1)

Also, it was felt it was not faculty’s role to teach students to write:

It is not our role, and it is assumed that they already have them [The skills to write in engineering]. [It is] Beyond the scope of the module. (EE2)

I think that there should be clear guidance from the teacher, but language should be pointed to [Library services]. (EE1)

I can’t spend too much time on those aspects. (ME1)

However, it was noted that students do need extra help learning to write in their discipline:

No [students are given writing instruction], that is the same in the UK. Students who come in with a BTEC do extra Maths, but there are no extra lessons in English...The Foundation [Year] keeps them well drilled. The students who do Year One in [China] are better prepared than a Chinese student who comes direct to the UK. (CE2)

After teaching the module I see I need to help them, but it is not part of our module. (CE1)

[This is a] Challenging area [teaching students how to write] in both contexts. (CS2)

Some UK students English is terrible. (CE2)

Also, some expressed an expansion of ESAP to all cohorts, both the UK students and the TNE students:

It is something that goes across all modules [Lack of teaching students to write in their discipline]. What you do in China should be replicated in the UK. If we had the time…it would be OK. External help is the most effective. (CE2)

Right now, [the insessional module] is just for the Joint School. Is there the possibility that in future it will also be done for the [Home cohort]? (ME1)

They would probably benefit from doing your course, except it is not open to them. (CS1)

However, one faculty member noted:

English teachers may not have had the experience of writing professional genres. (EE1)

Disciplinary expectations of the genres identified in research question 1

The final group of questions discussed one assessment identified in research question one for each respective faculty member. The questions include: what is considered a good submission? does structure, style, referencing, and language play a role? and, finally, what do students find the most difficult? The task explanation and what is considered a good submission helped to clarify the genre type in research question one and to help the course design on the insessional ESAP module. One key aspect that emerged was authentic assessment with audience awareness being important with students taking the role of an engineer:

Evaluating as a company manager. Considering multiple stakeholders. (ME 1) [Case Study]

Students need to draft a report and clearly explain what they are trying to do and show why they are a qualified transport planner. (CE1) [Problem Question]

The structure of the assessment was seen as important. As previously discussed, students are given clear briefs often with a detailed structure and they are expected to follow that. Two faculty members noted this increased structure of assessments can helps students, but also perhaps stifle creativity:

Because the brief is very explicit it is hard for them to do it badly...It is always that thing you are trying to give them structure without spoon feeding them. Because you do want those bright ones to shine, but you don’t want those that struggle to be held back. (CE2) [Design Specification]

The best students would do better without it [Given structure], but the average student is significantly helped. (CS2) [Design Specification]

The importance of language is discussed above. Interestingly the use of sources and referencing is largely ignored:

Have to include but no marks are given. This is the first piece of work that they have done where they have to reference. (CE2) [Design Specification]

No references’ [in this assessment]. (CE1) [Problem Question]

Referencing ideally would be included but it isn’t now. (EE2) [Explanation]

I do not ask them to reference. (CS2) [Design Specification]

However, genre conventions need to be considered and for some assessment it would not be expected:

In a journal or blog, you don’t need to reference. They can hyperlink. (EE1) [Mixed: Methodology Recount / Narrative]

The importance of referencing and source use was only discussed by two faculty:

Included as ACL format [For an ACL Format Research Report]. (CS1) [Research Report]

Referencing is important. Sources can come from company reports etc. I do check to see if they have referenced it. (ME1) [Case Study]

Finally, the faculty were asked what students find the most difficult when completing this assessment. This varied from understanding the question (EE2) ‘Comprehension issues, what is this question really asking me to do’ and writing concisely (CS1) ‘they struggle to be concise and stick to the word limit’ to developing arguments and critical reflection:

They struggle to compare and analyse between sections. (ME1) [Case Study]

Critical analysis – even home students miss out the critical analysis. (ME2) [Methodology Recount]

The majority of the material is assessed through this essay. They need to work in these theoretical ideas and include arguments...I am still struggling to get these arguments out of these students. Being able to form cohesive arguments at the sentence, paragraph and essay level. I am struggling to get this. (CS2) [Design Specification]

Not used to looking back and how effectively have I done it and how can I improve. (EE1) [Mixed: Methodology Recount / Narrative]

Results of the student questionnaire

The following section details the results from the student questionnaire to form part of the NA in response to research question three:

- What are the student’s prior knowledge & experience of these genres?

The questions were similar to the faculty semi structured interview questions to allow for comparison across faculty and student perceptions.

The importance of writing in the students’ discipline

Students were asked about how long they had been studying English and their motivations for studying Engineering. Students were also asked how important writing is in their chosen discipline. Only two students out of 72 respondents perceived writing to be ‘not very important’ and these were from CS and CE respectively. The majority of students felt it was ‘very important’ with reference to the importance of writing to show knowledge and complete reports.

Students experience and understanding of the genres identified in research question

The next questions asked students about their previous experience writing the genres identified in research question one for their discipline and asked them what their current understanding is for that particular genre. Overall, approximately 50% of students had some experience of the genres that they were required to complete and had a basic understanding of what was expected. The genre with the least experience was the Research Report genre as previously discussed above, and also the Problem Question genre, particularly in Mechanical Engineering (see Table 1 below).

| Genre | Computer Science | Electronic & Electrical | Mechanical Engineering | Civil Engineering |

| Methodology Recount | 50% Yes

50% No |

69% Yes

31% No |

||

| Narrative Recount | 55% Yes

45% No |

66% Yes

34% No |

78% Yes

22% No |

55% Yes

45% No |

| Design Specification | 82% Yes

18% No |

27% Yes

73% No |

78% Yes

22% No |

35% Yes

65% No |

| Case Study | 29% Yes

71% No |

|||

| Problem Question | 14% Yes

86% No |

36% Yes

64% No |

Table 1: Students’ previous writing experience

Learning to write in engineering

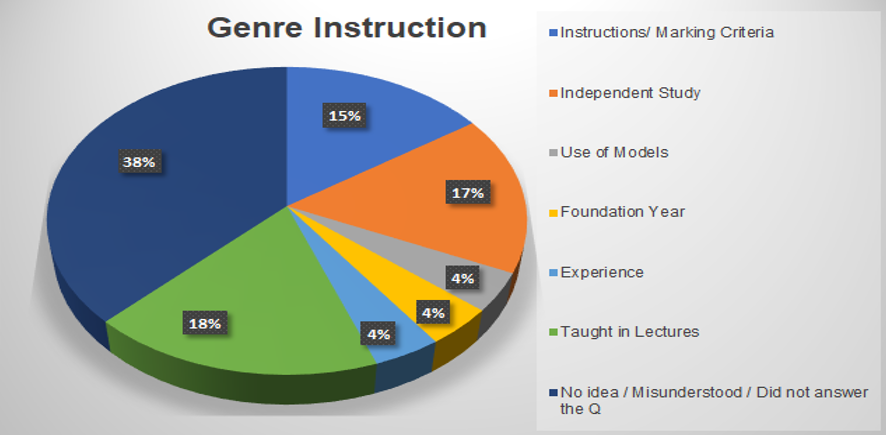

These final questions asked students how these engineering genres are taught and how they know what to include for a particular genre. Also, students were asked who they think should be responsible for teaching them to write as engineers. The majority of students stated they knew how to complete a particular assessment by analysing the writing brief, and through lectures. Past writing experience and independent study were also common answers (see Figure 2 below):

Figure 2: Genre instruction of assessed coursework

Figure 2: Genre instruction of assessed coursework

Finally, 49% of students responded that ‘the teacher’ should be responsible for teaching how to write in engineering. It is not clear if that teacher is an engineering or EAP teacher, but a few comments suggest the use of both:

Co-taught by professional teacher and English teacher.

English teacher and the teacher who teach engineering.

Both English teachers in charge of writing and engineering lecturers for professional courses. The former has a better understanding of the various literary techniques and theories of English writing than others, and the latter has a detailed knowledge of the norms of writing in specific engineering fields.

DISCUSSION

Genre analysis

This first discussion section considers the results of the genre analysis which was part of the target situation analysis (West, 1994). The results of the genre analysis found eight assessed writing genres across the Joint Engineering School. The Exercise genre (26%) was the most common with the Methodology Recount (9%) the second most common genre, and the Design Specification and Narrative Recount genre (6%) third, respectively. These frequencies correspond to Nesi and Gardner’s (2012) results found at Level Two in the Physical Sciences. The Methodology Recount (42.4%) was the most common with Design Specification (12.6%), Explanation and Critique (9.3%), Essay and Exercise (6%) and Narrative Recount (5.3%) genres the most frequent.

However, genre variation was found across the different disciplines. This is expected as each discipline ‘develops its own way of formulating and negotiating knowledge’ and how that may be expressed (Hyland, 2006b, p.21). The Narrative Recount, Exercise, and Design Specification were the only genres found across all four disciplines. Nesi and Gardner (2012, p.39) group the Design Specification genre within the ‘Preparing for Professional Practice’ social function, along with Case Studies, Problem Questions and Proposals, and found they were concentrated in ‘areas of manufacturing and computing’. This is reflected in these results, with engineering being vocational in nature and these students studying at year two of three of their undergraduate degree programme. Also, although Nesi and Gardner (2012) do not group the Narrative Recount genre within this social function, reflective writing can help students develop career skills, such as decision making, and professional judgment (Morrison, 1996; Gillett et al., 2009; Minnes et al, 2017). Interestingly, the Case Study genre was only found in Mechanical Engineering which mirrors Gillet and Hammond’s (2009, p.129) study of assessment at a UK university that found the ‘case studies appear to be underused given their relevance for employability.’ The Research Report genre was only used for three assessments (3%) and was only found in two of the four disciplines, Computer Science and Civil Engineering. However, students are expected to complete a final year research project and it was noted by faculty that students struggle with this genre. This may be due to the lack of experience in earlier years and will be discussed further below.

Student experience and understanding and genre instruction

This section considers the present situation analysis, which considers the learners' current genre experience, and the means analysis, which looks at the resources available to students (Ellison et al., 2017). White (1988) suggests this means analysis may be the most important consideration of a NA. The cross-analysis of the target situation analysis and students previous experience and understanding of these genres did not identify any significant ‘lacks’ in student experience and understanding (West, 1994; Jordan, 1997). Overall, students' experience and understanding were mixed, but only the Research Report and Problem Question were genres that students had not encountered before. In comparison with the means analysis, students were only explicitly taught how to write these genres in one module, and it was mostly assumed they have built experience from previous years of study. Students mostly learned how to write these genres through assignment prompts and marking criteria which confirms Wingate (2018, p. 352) suggestion that ‘the only explicit advice students receive in their study programmes is writing guidelines’ from module handbooks. Other resources students referred to included independent study and completion of the Foundation Year Programme. However, it was noted that the only time explicit writing instruction is given to the students is for the final year project. This lack of genre instruction was also clear when faculty were asked where the responsibility for writing instruction falls, with the faculty view that it was not their responsibility to teach students how to write as engineers. This remedial approach in the final year takes what Lea and Street (1998, pp.158159) call a ‘study skills’ approach and attempts to ‘fix’ student writing problems when required. Bond (2021, p.93) notes that this ‘further feeds into both content teachers’ and students’ beliefs that there is an academic linguistic norm to be met, and that can be met by correction of and learning discrete items, relating to punctuation, spelling, and grammar’. Through raising awareness, student difficulties are not seen as a linguistic deficit, but rather ‘new literacy and discourse practices’ (Hyland, 2018, p.384) or ‘academic literacy’ which need to be acquired by all students (Wingate, 2018, p.350). The pedagogical implications of this are discussed further below. On a positive note, the TNE context appears to have improved assessment practices with clear briefs and marking criteria.

Pedagogical implications

The immediate pedagogical implications of the NA have highlighted a need to include a variety of genre instruction on the ESAP in-sessional writing module. This instruction needs to be discipline-specific due to the variation across disciplines and can be explicit in teaching the structure, communicative purpose, and language choices used to construct the texts (Johns, 1997). Hyland (2003, p.149) states that grounding courses ‘in the texts that students will need to write in occupational, academic, or social contexts’ can help students participate effectively in their chosen community. The direct results of the NA have informed course design on the insessional ESAP module by including genre instruction for each of the assessed genres. Also, reflective writing has been included as an assessed genre on the insessional module as reflection was found across all four disciplines. This genre theory instruction at Level Two aims to address the issues related with the final year project by empowering students to develop their academic literacy through genre knowledge and genre-based writing skills. However, the NA has also highlighted the need for further writing instruction across all levels to address the lack of genre instruction and the remedial approach to writing on the final year projects.

Wider pedagogical implications regard the role of language and collaboration across the school. English communication was seen as important across engineering. However, this is not often reflected in how students are graded with few, if any, marks awarded for language. Also, although the assessment briefs are well structured and clear marking criteria are given, these may not always be understood by the students without further explanation which highlights the importance of students’ assessment literacy. For example, some faculty expressed the view that students found argumentation and being critical difficult. These concepts are often obscure and vague for students, whereas faculty may view these as simple and easily understood terms used to express expected conventions (Lillis and Turner, 2001; Wingate, 2018). Consequently, this lack of clarity as Caplan (2019) states ‘can be challenging for students to correctly identify the purpose, form, conventions, stance, and language demands - that is, the genre - of an effective response’. To overcome these issues Bond (2021, p.126) advocates an ‘integrated approach where language becomes visible’ to increase the value of language learning to that of content knowledge. To do this, increased collaboration is required between EAP and subject specialists to enhance students' academic literacy development (Wingate, 2018; Bond, 2021). Needs analysis such as this, may help increase this collaboration and highlight the need for increased academic literacy support including increased genre awareness and assessment literacies to help students communicate effectively in their chosen disciplines.

CONCLUSION

This case study carried out a needs analysis of the assessed writing genres of a second-year transnational education engineering programme. The results highlighted eight assessed writing genres across the four engineering disciplines. Analysis of the importance and the role of English within engineering; and students' understanding and experience of these genres, has highlighted areas for curriculum development on the insessional ESAP module. These include raising genre awareness of the assessed writing genres in each discipline and the teaching of reflective writing to help students develop lifelong skills and prepare for professional practice.

Although the case study was based on this particular context, and as disciplines are context-specific, the results may not be generalisable to other contexts, the methodology may be used to conduct NA in other contexts and inform insessional or academic literacy provision in different disciplines. Also, this study has highlighted possible areas for development including increased cooperation between EAP specialists and subject specialists to further develop students' academic literacy. Further research is required within this context including deeper analysis of the genres highlighted in each discipline and also analysis of the assessed writing genres across all levels of study in this context.

Address for correspondence: m.ketteringham@leeds.ac.uk

REFERENCES

Anthony, L. 2019. Introducing English for specific purposes. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Asaoka, C. and Usui, Y. 2003. Students’ perceived problems in an EAP writing course. JALT Journal. 25(2), pp.143 172.

Bacha, N.N. and Bahous, R. 2008. Contrasting views of business students’ writing needs in an EFL environment. English for Specific Purposes. 27(1), pp.74-93.

Bocanegra-Valle, A. 2016. Needs analysis for curriculum design. In: Hyland, K and Shaw, P. eds. The Routledge handbook of English for academic purposes. London: Routledge, pp.560-576.

Bond, B. 2021. Making language visible in the university: English for academic purposes and internationalisation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Bozdogan, D. and Kasap, B. 2019. Writing skills and communication competence of undergraduate students in an engineering English course. The Journal of Language Teaching and Learning. 9(2), pp.49-65.

Braine, G. 1995. Writing in the natural sciences and Engineering. In: Belcher, D. and Braine, G. eds. Academic writing in a second language. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corporation, pp.113-134.

Brown, J.D. 2016. Introducing needs analysis for English for specific purposes. Routledge: Abingdon.

Bruce, I. 2011. Theory and concepts of English for academic purposes. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Caplan, N.A. 2019. Asking the right questions: demystifying writing assignments across the disciplines. Journal of English for Academic Purposes. 41, pp.1475-1585.

Chambers, F. 1980. A re-evaluation of needs analysis in ESP. The ESP Journal. 1(1), pp.25-33.

Codó, E. 2008. Interviews and questionnaires. In: Wei, L., and Moyer, M.G. eds. The Blackwell guide to research methods in bilingualism and multilingualism. Hoboken: Backwell, pp.158-176.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K. 2011. Research methods in education. 7th ed. Oxon: Routledge.

Conrad, S. 1996. Investigating academic texts with corpus-based techniques: an example from biology. Linguistics and Education. 8, pp.299-326.

Davies, J.A., Davies, L.J., Conlon, B., Emerson, J., Hainsworth, H. and McDonough, H.G. 2020. Responding to COVID-19 in EAP contexts: a comparison of courses at four Sino-foreign universities. International Journal of TESOL Studies. 2(2), pp. 32-51.

Denscombe, M. 2014. The good research guide. 4th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Doody, S. and Artemeva, N. 2021. “Everything is in the lab book”: multimodal writing, activity, and genre analysis of symbolic mediation in medical physics. Written Communication. 39(1), pp.1-41.

Du, J. and Shi, J. 2018. Taking needs into deeds: application of needs analysis in undergraduate EAP course design. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics. 41(2), pp.182-203.

DudleyEvans, T. and St John, M. 1998. Developments in English for specific purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ellison, M., Aráujo, S., Correia, M. and Vierra, F. 2017. Teachers’ perceptions of need in EAP and ICLHE contexts. In: Valcke, J. and Wilkinson, R. eds. Integrating content and language in higher education: perspectives on professional practice. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp.59-76.

Gardner, S., Nesi, H. and Biber, D. 2019. Discipline, level, genre: integrating situational perspectives in a new MD analysis of university student writing. Applied Linguistics. 40(4), pp.646-674.

Gillett, A., Hammond, A. and Martala, M. 2009. Successful academic writing. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Gimenez, J. 2008. Beyond the academic essay: discipline specific writing in nursing and midwifery. Journal of English for Academic Purposes. 7, pp.151-164.

Hale, G., Taylor, C., Bridgeman, B., Carson, J., Kroll, B. and Kantor, R. 1996. A study of writing tasks assigned in academic degree programmes. TOEFL Research Report No. 54. [Online]. Princeton: Educational Testing Service. [Accessed 25 September 2021]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.1995.tb01678.x

Hammersley, M. and Traianou, A. 2012. Ethics and educational research, British Educational Research Association on-line resource. [Online]. [Accessed 13 June 2021]. Available from: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethics-and-educational-research

Holliday, A. 1994. Appropriate methodology and social context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Horowitz, D.M. 1986. What professors actually require: academic tasks for the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly. 20(3), pp.445-462.

Hsu, W. 2014. Measuring the vocabulary load of engineering textbooks. English for Specific Purposes. 33, pp.54-65.

Hutchinson, T. and Waters, A. 1987. English for specific purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hyland, K. 1997. Scientific claims and community values: articulating an academic culture. Language & Communication. 17, pp.1921.

Hyland, K. 2000. Disciplinary discourses: social interactions in academic writing. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

Hyland, K. 2003. Genre pedagogy: language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing. 16(3), pp.148-164.

Hyland, K. 2006a. English for academic purposes: an advanced resource book. Oxon: Routledge.

Hyland, K. 2006b. Disciplinary differences: language variation in academic discourses. In: Hyland, K. and Bondi, M. eds. Academic discourse across disciplines. Frankfort: Peter Lang, pp.17-45.

Hyland, K. 2009. Writing in the disciplines: research evidence for specificity. Taiwan International ESP Journal. 1(1), pp.5-22.

Hyland, K. 2018. Sympathy for the Devil? A defence of EAP. Language Teaching. 51(3), pp.383-399.

Hyland, K. and Hamp-Lyons, L. 2002. EAP: issues and directions. Journal of English for Academic Purposes. 1, pp.1-12.

Hyland, K. and Tse, P. 2009. Academic lexis and disciplinary practice: corpus evidence for specificity. International Journal of English Studies. 9(2), pp.111-129.

Hyon, S. 2018. Genre and English for specific purposes. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hyon, S. 1996. Genre in three traditions: implications for ESL. TESOL Quarterly. 30(4), pp.693722.

Jackson, L., Meyer, W. and Parkinson, J. 2006. A study of the writing tasks and reading assigned to undergraduate science students at a South African university. English for Specific Purposes. 25, pp.260-281.

Johns, A. M. 1997. Text, role and context: developing academic literacies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jordan, R.R. 1997. English for academic purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lea, M. R. 2004. Academic literacies: a pedagogy for course design. Studies in Higher Education. 29(6), pp.739- 755.

Lea, M.R. and Street, B.V. 1998. Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education. 23(2), pp.157172.

Leki, I. and Carson, J. G. 1994. Students' perceptions of EAP writing instruction and writing needs across the disciplines. TESOL Quarterly. 28(1), pp.81-101.

Leki, I. and Carson, J. 1997. “Completely different worlds”: EAP and the writing experiences of ESL students in university courses. TESOL Quarterly. 31(1), pp.3969.

Lillis, T. M. and Turner, J. 2001. Student writing in higher education: contemporary confusion, traditional concerns. Teaching in Higher Education. 6(1), pp.57-68.

Long, M.H. 2005. Second language needs analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nesi, H. and Gardner, S. 2006. Variation in disciplinary culture: university tutors' views on assessed writing tasks. British Studies in Applied Linguistics. 21, pp.99117.

Nesi, H. and Gardner, S. 2012. Genre across the disciplines: student writing in higher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Minnes, M., Mayberry, J., Soto, M. and Hargis, J. 2017. Practice makes deeper? Regular reflective writing during engineering internships. Journal Of Transformative Learning. 4(2), pp.7-20.

Morrison, K. 1996. Developing reflective practice in higher degree students through a learning journal. Studies in Higher Education. 21(3), pp.317-332.

Parkinson, J. 2017. The student laboratory report genre: a genre analysis. English for Specific Purposes. 45, pp.1-13.

Paltridge, B. 2004. Academic writing. Language Teaching. 37, pp.87-105.

Peacock, M. 2002. Communicative moves in the discussion section of research articles. System. 30, pp.479-497.

Rahman, M., Ming, T.S., Aziz, M.S.A. and Razak, N.A. 2009. Needs analysis for developing an ESP writing course for foreign postgraduates in science and technology at the National University of Malaysia. The Asian ESP Journal. 5(2), pp.34-59.

Richards, J.C. and Schmidt, R. W. 2002. Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied Linguistics. 3rd ed. New York: Longman.

Rubin, H. J. and Rubin, I. S. 2012. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Serafini, E. J., Lake, J. B. and Long, M. H. 2015. Needs analysis for specialized learner populations: essential methodological improvements. English for Specific Purposes. 40, pp.11-26.

Shamsudin, S., Manan, A. and Husin, N. 2013. Introductory engineering corpus: a needs analysis approach. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences. 70, pp.1288-1294.

Songhori, M.H. 2008. Introduction to needs analysis. English for Specific Purposes World. 4(7), pp.1-25.

Swales, J. M. 1990. Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vardi, I. 2000. What lecturers’ want: an investigation of lecturers’ expectations in first year essay writing tasks. The Fourth Pacific Rim - First Year in Higher Education Conference: Creating Futures for a New Millennium. 5-7 July. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

Ward, J. 2009. A basic engineering English word list for less proficient foundation engineering undergraduates. English for Specific Purposes. 28, pp.170182.

Wardle, E. 2009. “Mutt genres” and the goal of FYC: can we help students write the genres of the university? College Composition and Communication. 60(4), pp.765-789.

Webster, S. 2021. The written discourse genres of digital media studies. In: Whong, M. and Godfrey, J. eds. What is good academic writing?: insights into discipline-specific student writing. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 31-56.

West, R. 1994. Needs analysis in language teaching. Language Teaching. 27(1), pp.119.

Wingate, U. 2018. Academic literacy across the curriculum: towards a collaborative instructional approach. Language Teaching. 51(3), pp.349–364.

Woodrow, L. 2018. Introducing course design in English for specific purposes. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wu, J. and Lou, Y. 2018. Needs analysis of Chinese chemical engineering and technology undergraduate students in Yangtze University in English for specific purposes. Creative Education. 9, pp.2592-2603.

Zhu, W. 2004a. Faculty views on the importance of writing, the nature of academic writing, and teaching and responding to writing in the disciplines. Journal of Second Language Writing. 13, pp.29-48.

Zhu, W. 2004b. Writing in business courses: An analysis of assignment types, their characteristics, and required skills. English for Specific Purposes. 23, pp.111-135.

APPENDIX

The Classification of Genre Families (Nesi and Garner, 2012)

| Genre Families | Educational Purpose/

Generic Structure/ Genre Network |

Genre Examples |

| 1. Case Study | - To Demonstrate/develop an understanding or professional practice through the analysis of a single exemplar

- Description of a particular case, often multifaceted, with recommendations or suggestions for future action -Typically corresponds to professional genres (e.g. in business, medicine and Engineering) |

Business Start-up

Company Report Organisation Analysis Patient Report Single Issue |

| 2. Critique | -To demonstrate/develop understanding of the object of study and the ability to evaluate and/or assess the significance of the obejct of study

-Includes descriptive account with optimal explanation and evaluation with optional tests -May correspond to part of a Research Report, professional Design Specification or to an expert evaluation such as a book review |

Academic Paper Review

Approach Evaluation Organisation Evaluation Financial Evaluation Interpretation of Results Legislation Evaluation Policy Evaluation Building Evaluation Project Evaluation Book/Film/Website Review System Evaluation |

| 3. Design Specification | -To demonstrate/develop the ability to design a product or procedure that could be manufactured or implemented

-Typically includes purpose, design development and testing of design -May correspond to a professional design specification, or to part of a Proposal or Research Report |

Application Design

Building Design Database Design Game Design Label Design Product Design System Design Website Design |

| 4. Empathy Writing | -To demonstrate/develop understanding and appreciation of the relevance of academic ideas by translating them into a non-academic register, to communicate to a non specialist readership

-May be formatted as a letter, newspaper article or similar non-academic text -May correspond to private genres as in personal letters to publically available genres such as information leaflets |

Expert advice to industry

Expert advice to lay person Information Leaflet Job Application Letter to a Friend News Report |

| 5. Essay | -To demonstrate/develop the ability to construct coherent argument and employ critical thinking skills

-Introduction, series of arguments, conclusion -May correspond to a published academic/specialist paper |

Challenge

Commentary Consequential Discussion Exposition Factorial |

| 6. Exercise | -To provide practice in key skills (e.g. the ability to interrogate a database, perform complex calculations, or explain technical terms or procedures), and to consolidate knowledge of key concepts

-Data analysis of a series of responses to questions -May correspond to part of a Methodology Recount or Research Report |

Calculations

Short Answers Mixed Data Analysis Statistics Exercises |

| 7. Explanation | -To demonstrate/develop understanding of the object of study and the ability to describe and/or account for its significance

-Includes descriptive account and explanation -May correspond to a published Explanation, or to part of a Critique or Research Report |

Business Explanation

Instrument Description Methodology Explanation Organism/Disease Account Site/Environment Report Species/Breed Description System/Process Explanation Account of Phenomenon |

| 8. Literature Review | -To demonstrate/develop familiarity with literature relevant to the focus of study

-Includes summary of literature relevant to the focus of study and varying degrees of critical evaluation -May correspond to a published review article or anthology, or to part of a REsearch Report |

Analytical Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Anthology Literature Review Literature Overview Research Methods Review Review Article |

| 9. Methodology Recount | -To demonstrate/develop familiarity with disciplinary procedures, methods, and conventions for recording experimental findings

-Describes procedures undertaken by writer and may include Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections -May correspond to part of a Research Report or published research article. |

Computer Analysis Report

Data Analysis Report Experimental Report Field Report Forensic Report Lab Reports Materials Selection Report Program Development Report |

| 10. Narrative Recount | -To demonstrate/develop awareness of motives and/or behaviour in individuals (including self) or organisations

-Fictional or factual recount of events, with optional comments -May correspond to published literature, or to part of a Research Report |

Accident Report

Account of Literature Search Account of Website Search Biography Character Outline Plot Synopsis Reflective Account |

| 11. Problem Question | -To provide practice in applying specific methods in response to professional problems

-Problem (may not be stated in assignment), application of relevant arguments or presentation of possible solutions in response to scenario -Problems or situations resemble or are based on real legal, engineering, accounting or other professional cases |

Business Scenario

Law Problem Question Logistics Simulation |

| 12. Proposal | -To demonstrate/develop ability to make a case for future action

-Includes purpose, detailed plan, persuasive argumentation -May correspond to professional or academic proposals |

Book Proposal

Building Proposal Business Plan Catering Plan Legislation Reform Marketing Plan Policy Proposal Research Proposal |

| 13. Research Report | -To demonstrate/develop ability to undertake a complete piece of research including research design, and an appreciation of its significance in the field

-Includes student’s research aim/question, investigation, links and relevance to other research in the field -May correspond to a published experimental research article or topic based research paper. |

Research Article

Student Research Project Topic-based Dissertation |