A delineation of variation in Arabic between fuṣḥá and Egyptian ’āmmīyah

University of Cambridge, Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies

Abstract

Since the description of Arabic as a diglossic language by Ferguson (1959a), much attention has been paid to refining this description of the Arabic language situation, and outlining the features of its distinct Standard and dialectal forms. Underlying this view, however, is that Arabic is a single, unified language with a large number of shared items between its Standard and dialectal forms. What has been missing from the equation is a comprehensive study of the exact differences between the Standard and dialectal forms, and the level of variation that exists between them. It is the purpose of this study, therefore, to begin to outline these differences, by comparing the features of Standard and Egyptian (Cairene) Arabic. The study identifies three levels of difference between the two forms: phonological, lexical and grammatical, illustrating each with a number of examples. The study is a starting point for comparing between Standard Arabic and other dialects, as well as between the dialects themselves.

A note on transliteration scheme

This paper employs the Library of Congress romanisation scheme. For the full transliteration scheme, please see Appendix 1.

KEYWORDS: Arabic, diglossia, variation, sociolinguistics, Egyptian

Introduction

It is widely accepted in our field that variation in Arabic exists between its Standard and dialectal forms. The question of how they vary however, is an area ripe for research and one that this study aims to address. While studies of the phonology, grammar, lexicon and syntax of some dialectal forms are available, such as Willmore (1927), Harrell (1957), Khalafallah (1969), Abdel-Malek (1972a), Wise (1975), Mitchell (1978), Abdel-Massih et al. (1979), Abdel-Jawad (1981), Elgibali (1985), Norlin (1987), Holes (1990), Mitchell and El-Hassan (1994) and Cowell (2005), what seem to be lacking are more direct comparisons between Standard Arabic (fuṣḥá) and the dialectal forms (‘āmmīyah). This study therefore, aims to begin to bridge this gap by offering a delineation of the variation between fuṣḥá and Egyptian ‘āmmīyah on three levels: phonological, lexical and grammatical (morphological and syntactic).

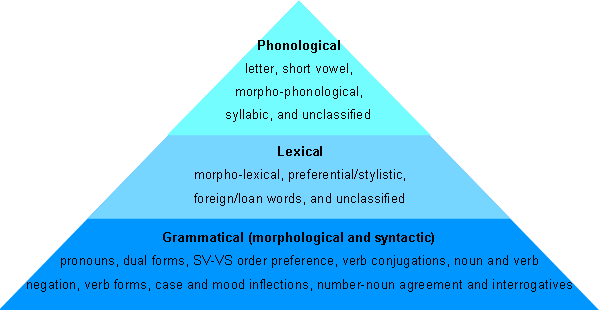

After completing this study, the author came across Gadalla (2000), a comparative study of the morphology of Standard and Egyptian (Cairene) Arabic. Another, smaller study compares the phonological features of the Tunisian Arabic dialect with Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and Egyptian (Cairene) Arabic (Zribi et al., 2014). While there is some overlap between Gadalla (2000) and this study, the former is more concerned with the morphological aspects of the verb forms of Arabic, with a comparative analysis of the phonology of the Standard (fuṣḥá) and dialectal (‘āmmīyah) forms in the introduction to the study, whereas this study is concerned with conceptualising the overall variation between the two forms, and offers a hierarchical view and summary of the main differences between the two forms. The hierarchical view is presented visually as a pyramid with three levels, to represent the phonological, lexical and grammatical (including morphological and syntactic) differences. Furthermore, this study is part of a wider study that proposes a theoretical framework for Arabic writing, including fuṣḥá, ‘āmmīyah and mixed varieties. So the purpose here is to understand the underlying similarities and differences between the two forms, in order to develop a wider framework for analysing the various forms of Arabic writing.

The underlying assumption of this study is that the Arabic language is one, unified language and that its fuṣḥá and dialectal ‘āmmīyah forms share many common features, while at the same time having variations, or rather degrees of variation between them. Each form serves its own sociolinguistic functions, and mixing between the two can in turn serve specific sociolinguistic functions. Variation between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīya can subsequently be treated as a subset of the language, and the degree to which they vary can be assessed more objectively.

In understanding not only the exact differences but the level of variation that exists between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, we are able to more accurately study instances of mixed-language use (both in speaking and writing), or code-mixing and code-switching. In fact, leading studies of these, such as Eid (1982, 1988) and Bassiouney (2006, 2013), have highlighted the problem of dealing with so-called ambiguous or shared forms that are neither exclusively fuṣḥá nor ‘āmmīyah, but exist in both, and in some cases are ignored or excluded altogether from critical analysis of code-switching patterns.

This leads us to the need for a comprehensive framework outlining the variations between the two forms, including a hierarchical structure of the degree of variation that exists between them. This study therefore, offers a starting point for the delineation of the variation between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, using Cairene Egyptian Arabic as a starting point to provide a model that can be used with other dialects, since it is one of the most well studied and documented varieties of Arabic, as shown in the studies mentioned above. The model provides a visual breakdown of the degree of difference between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīya, categorised as phonological, lexical and grammatical (morphological and syntactic).

Examples and sometimes extensive examples of each category are included to show what is meant by, as well as to document, each language feature, highlighting the nuance in variation, in order to determine the overall degree of variation between the language features. Given the aim of viewing the Arabic language as a unified whole with regular and predictable variations between its fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah forms, the levels of variation identified as part of this study are outlined in Figure 1 below:

To begin with, Phonological variations are those which describe predictable variations in the pronunciation of particular sounds between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, in otherwise identical shared words. Next, Lexical variations are those where a different lexical item is used in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah to describe the same thing. Finally, grammatical variations are those which exist in the grammatical system, including morphological and syntactic differences. A detailed outline of all three aspects is presented below.

Phonological variation

This first category covers the large group of words that are the same in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, except for their being pronounced slightly differently in each, with these differences conforming to general rules. This group of words is easily ‘disguised’ in mixed writing where the writer makes use of as much shared vocabulary as possible in order for the text to sound as close to spoken speech as possible. Thus, in terms of spelling and orthography the words appear identical, although they are in fact pronounced differently between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah. This style of writing has been described as ‘strategic bivalency’ (Woolard, 1999; Woolard, K. and Genovese, E., 2007; Mejdell, 2014). This group can be further divided into: expected letter variation, short vowel variation, morphological variation and unclassified variation.

Expected letter variation

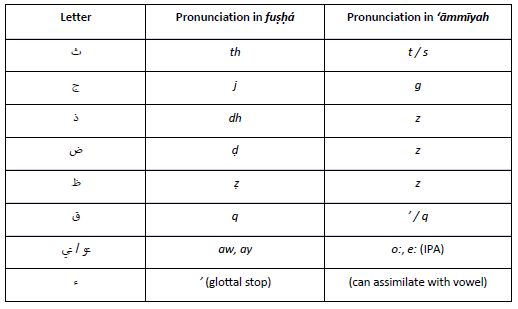

If we look at the Arabic alphabet, we expect and indeed do find it is the same in fuṣḥá and Egyptian ‘āmmīyah, i.e. there are no characters that are exclusive to either form. However, we find in Egyptian ‘āmmīyah that the pronunciation of a specific group of letters varies from that of fuṣḥá, whether in some cases or all. These are: ث ذ ظ ج ض ق و/ي ء as described below:

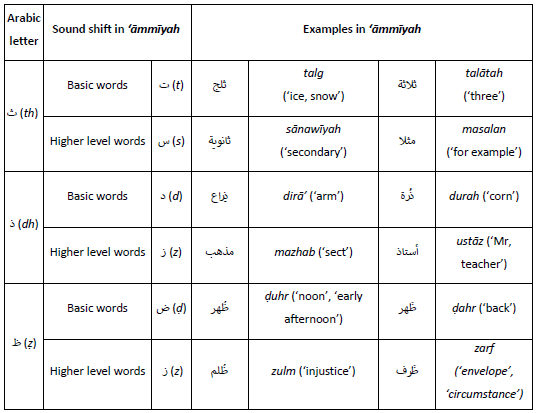

Interdentals: ث ذ ظ[1]

Egyptian Arabic and most other sedentary dialects lost the interdentals ث (th), ذ (dh) and ظ (ẓ), which have shifted to different sounds in basic and higher-level (more formal, technical or scientific) words as follows:

- th has generally shifted to t in basic contexts and to s in higher-level contexts;

- dh has shifted to d in basic contexts and to z in higher-level contexts;

- ẓ has shifted to ḍ in basic contexts and to ẓ in higher-level contexts.

The letter ج in Egypt is normally pronounced as a plosive /g/ )IPA) rather than the voiced postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ (ibid.) in both fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah except in recitations of the Qur’an. /g/ is, in fact, the older pronunciation of ج; i.e. Egyptian Arabic has preserved something which is older than the pronunciation ‘j’ (Woidich and Zack, 2009).

The letter ض is pronounced ḍ as it is in fuṣḥá, except in some cases where it is pronounced as z in ‘āmmīyahg. the pronunciation of ضابط (ḍābit, ‘officer’) as زابط (zābit).

Table 1: Interdental sound shifts in Egyptian ‘āmmīyah

The letter ق pronounced often as the glottal stop (hamzah) ء in ‘āmmīyah but not always. Again, the pronunciation with ‘q’ is usually found in words borrowed from Standard Arabic. Some examples of pronunciation of this letter are:

- قال (’āl, ‘said’) : where the ق is pronounced as the glottal stop (hamzah) ء;

- قضية (‘issue’, ‘case/lawsuit’): where pronunciation ofق can alter the meaning of the word - المرأة قضية pronounced qadīyat al-mar’a, to mean ’women’s issue’ is different to the pronunciation raf‘ ’adīyah, meaning ‘to file a lawsuit’; similarly قوي pronounced qawī to mean ‘strong’, but pronounced ’awī to mean ‘very’

- قانون (qānūn, ‘law’): where ق is nowadays normally pronounced

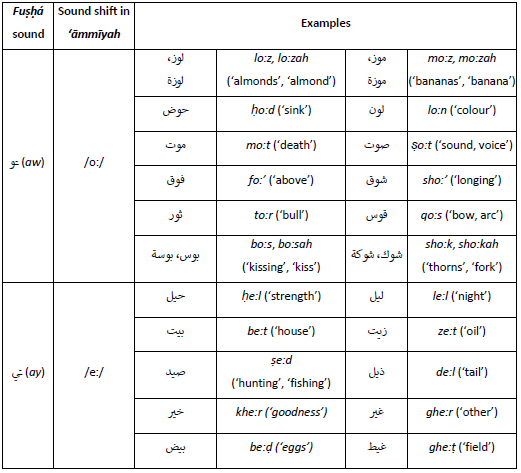

- The diphthongs ـــــَـو /ـــــَي (ay / aw): where in fuṣḥá the و (w) and ي (y) consonants are preceded by a fatḥa making aw and ay sounds respectively, they shift to long vowel sounds unique to ‘āmmīyah, represented by the IPA sounds /oː/ and /eː/ as in Table 2 below. Several examples are given for each sound shift to illustrate how common it is to find this sound shift in ‘āmmīyah, with some examples containing expected letter variations, as outlined above:

Table 2: Diphthong sound shifts in Egyptian ‘āmmīyah

The hamzah glottal stop ء : assimilates with the ā or ī vowel ‘chair’ in some cases when:

- preceded by a fatḥa and followed by sukūng. رأس (ra’s, ‘head’) pronounced as راس (rās), similarly فأس (fa’s, ‘axe’) pronounced as فاس (fās) and كأس(kā’s, ‘cup’) pronounced as kās;

- medial in the active participle فاعل form e.g. صائم (ṣā’im, ‘fasting’) pronounced as صايِم (ṣāyim), similarlyطائر (ṭā’ir, ‘flying’, ‘bird’) pronounced as طايِر (ṭāyir) and نائم (nā’im, ‘sleeping’) pronounced as نايِم nāyim;

- on or beside final alif (e.g. سماء (samā’, ‘sky’) pronounced as سما (sama) and مساء (masā’, ‘evening’) pronounced as مسا (masa or misa).

Table 3: Summary of expected letter variation between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah

Short vowel variation

These are words whose letters are orthographically identical, however the difference in pronunciation between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah is in the (unwritten) short vowels, such as: مَهَمّة (mahammah, ‘task’) and مُهِمّة (muhimmah). This is also, of course, true of a lot of purely fuṣḥá words.

Morpho-phonological variation

This includes a slight variation in pronouncing morphological suffixes or prefixes. A purely phonological variation, it has no grammatical implication i.e. the word order and usage remain the same as in fuṣḥá. Examples include:

- the nisbah adjective ending يّ (īy) in fuṣḥá pronounced without the shaddah as ي (ī) in ‘āmmīyah

- the definite article الـ (al) pronounced as il in ‘āmmīyah, as in البنت pronounced ilbint and الولد pronounced ilwalad

- The feminine marker اء (ā’) in fuṣḥá used for colours is pronounced in ‘āmmīyah without the final hamza and with a shortening of the final ā to become simply a short a as in حمراء ‘red’ pronounced ḥamrā’ in fuṣḥá but ḥamra in ‘āmmīyah.

Syllable variation

This refers to the vowel dropping rules in ‘āmmīyah, such as dropping of the kasrah and shortening of the alif in the feminine singular active particle فاعِلة (fā‘ilah) form, as in: سامِعة (sāmi‘ah, hear/s) which is pronounced sam‘ah in ‘āmmīyah; similarly كامِلة (kāmilah, complete) is pronounced kamlah, and شاملة (shāmilah, comprehensive) is pronounced shamlah.

Unclassified phonological variation

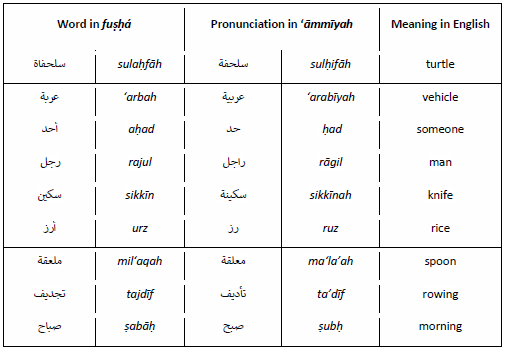

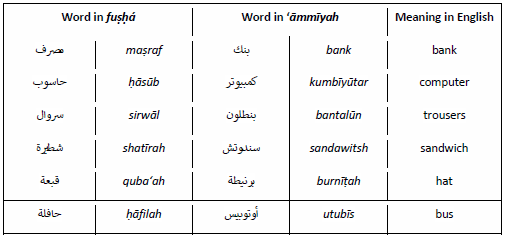

Words that do not have an immediately identifiable overarching category for the variation such as the examples in Table 4 below, and have not been identified as part of a wider group or pattern, although they are simple nouns and appear to have no distinct phonological or morphological variation pattern:

Table 4: Examples of unclassified phonological variation

Lexical variation

Whereas the previous category, that of phonological variation, was limited to variation between single sounds, this second group refers to the variation between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah in single lexical items. From experience teaching Arabic as a Foreign Language using the Integrated Approach i.e. teaching fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah side by side from the very beginning, the author has encountered this type of lexical variation that does not seem to have been categorised before, a view shared by Abdel-Malek (1972b, p.138). This category can be subdivided into morphological variations, preferential/stylistic variations, foreign/loan words, and unclassified variations:

Morpho-lexical variation

Between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah we find shared identical lexical items, such as تفاح (tuffāḥ, ‘apples’), كرسىي (kursī, ‘chair’) and باب (bāb, ‘door’). In terms of variation, we have identified above identical lexical items that contain a defined phonological variation such as for example جامع (jāmi‘, ‘mosque’) pronounced with the expected letter variation as gāmi‘. This category, however, is concerned with non-identical lexical items that share the same meaning and root. The variation in this group differs from the unclassified phonological variation outlined above, in that the variation extends beyond a phonological variation to the morphology of the word itself, and yet the lexical pairs still share the same meaning and root. So for each lexical pair in this category we find a distinct morphological pattern for the fuṣḥá lexical item and at the same time we find that the corresponding ‘āmmīyah lexical item deviates from the fuṣḥá morphological pattern, while retaining the same meaning and root. Some examples of morpho-lexical variations and their morphological patterns in fuṣḥá are given in Table 5 below:

Table 5: Examples of morpho-lexical variation

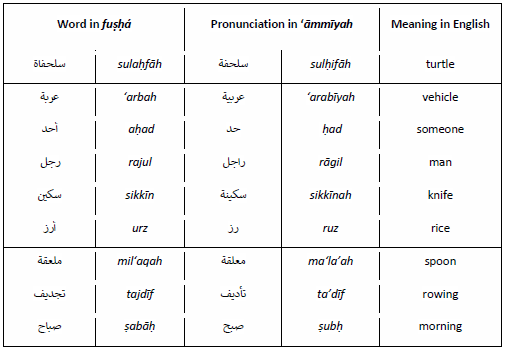

Preferential/stylistic variation

This describes the ‘shared’ group of words between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah in that they exist in both varieties, but tend to be used in one variety rather than the other, therefore acquiring either a fuṣḥá or ‘āmmīyah ‘flavour’ (Abdel-Malek, 1972b). Examples in Table 6 below:

Table 6: Examples of preferential/stylistic variation

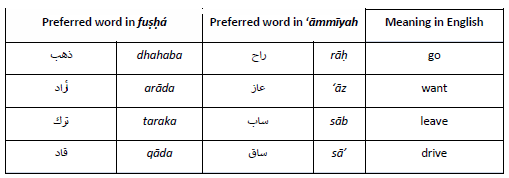

Foreign or loan words

These are commonly-used foreign or loan words in ‘āmmīyah which in some cases have been absorbed into fuṣḥá and in other cases the fuṣḥá has been absorbed into ‘āmmīyah. In most of these cases however, the Arabic form is in fact a neologism designed to replace the foreign borrowing form with a ‘genuine’ Arabic form, as in the examples in Table 7 below, including some examples from Abdel-Malek (1972):

Table 7: Examples of foreign words

Unclassified lexical variation

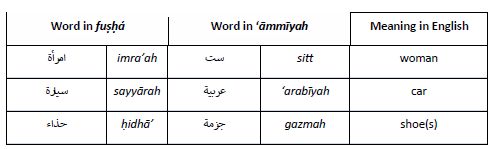

This is the case where different lexical items are used in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, but neither form is shared with the other, such as (ستّ - امرأة؛ عربية - سيارة ؛ جزمة - حذاء)

Table 8: Examples of undefined lexical variation

Grammatical (morphological and syntactic) variation

Perhaps the largest subgroup of differences between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, it includes (but is not limited to): personal, demonstrative and relative pronouns; dual forms; SV-VS order preference; verb conjugations; case and mood inflections; noun and verb negation; number-noun agreement; interrogatives; and verb forms.

Pronouns

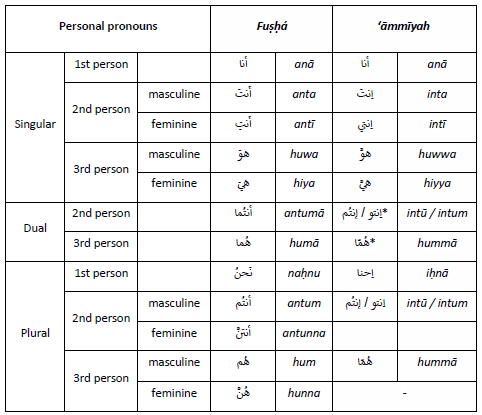

Personal pronouns: the number of distinct personal pronouns in fuṣḥá (12) is larger than the number in ‘āmmīyah (8). The eight personal pronouns of ‘āmmīyah overlap with the personal pronouns in fuṣḥá, and are largely similar, with some phonetic variation as shown in the table below:

Table 9: Personal pronouns in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah

There is no dual pronoun in ‘āmmīyah, so the plural pronouns are used.

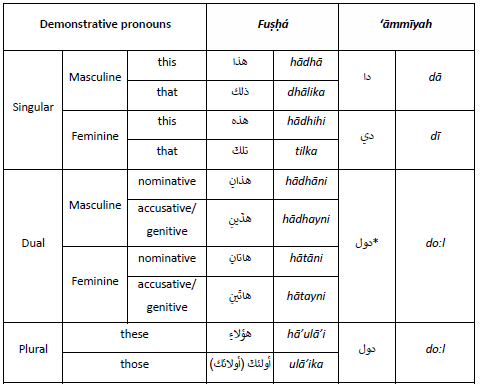

Demonstrative pronouns: the ten demonstrative pronouns in fuṣḥá are reduced to three in ‘āmmīyah (دا - دي - دول) as shown in Table 10 below:

There is no dual demonstrative pronoun in ‘āmmīyah, so the plural demonstrative is used instead.

In terms of agreement in ‘āmmīyah, we see the dual noun taking the plural demonstrative, as in الكتابين دول (il-kitābe:n do:l, 'these (pl.) [two] books (dual)’).

Table 10: Demonstrative pronouns in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah

Additionally, while there is no syntactic difference in the use of the demonstrative pronouns between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah when together with a noun they form a complete equational sentence. However, as a demonstrative-noun phrase their order is reversed. For example:

| ‘This [is a] book’ | da kitāb | دا كتاب | = | hādhā kitāb | هذا كتاب |

| ‘This book [is] beautiful’ | il-kitāb da gamīl | الكتاب دا جميل | = | hādhā al-kitāb jamīl | هذا الكتاب جميل |

Relative pronouns: as with demonstrative pronouns, the number of relative pronouns is greatly reduced in ‘āmmīyah. In fact, there is only one relative pronoun in ‘āmmīyah, compared with nine in fuṣḥá. The grammatical use of the relative pronoun is the same as in fuṣḥá, where it is used in a relative clause with a definite noun, and omitted when the noun is indefinite, as in:

| ‘A man [who] works in a factory’ | راجل بيشتغل* في مصنع | = | رجل يعمل في مصنع |

| ‘The man who works in a factory’ | الراجل اللي بيشتغل* في مصنع | = | الرجل الذي يعمل في مصنع |

The verb عمل - شغل is an example of preferential/stylistic lexical variation. (For the b+ imperfect verb suffix see case and mood inflections below.)

Dual forms

As seen above, while the dual form is present in fuṣḥá, it is largely absent in ‘āmmīyah since there are no dual pronouns, demonstrative pronouns or relative pronouns in ‘āmmīyah. The same is true for verbs, since there are no dual pronouns in ‘āmmīyah, there are no dual verb conjugations. The dual is present in ‘āmmīyah in the case of counted nouns only, which take the the ين ending pronounced as /e:n/ (see Table 2 above and Table 11 below), without modification for gender or case. For example, ‘two books’ is كتابين (kitābe:n) without the use of the number ‘two’ except for emphasis, as is the case in fuṣḥá, in which case it would be اتنين كتابين (kitābe:n itne:n).

SV-VS order preference and agreement

In both fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, both verb-subject or subject-verb order are used. However, in fuṣḥá the preference is V-S order while in ‘āmmīyah the preference is S-V order. Whereas in fuṣḥá the verb in V-S order is singular, in ‘āmmīyah the verb agrees with the subject in number (singular or plural).

Verb conjugations

- Dual: the absence of dual pronouns and the third person feminine plural pronouns in ‘āmmīyah naturally results in no verb conjugations for these pronouns in ‘āmmīyah (instead the dual is conjugated as a plural).

- Imperfect verb conjugation: largely similar, except in ‘āmmīyah we see the dropping of the final ن /n/ in the second person feminine singular conjugationين (īn) in fuṣḥá to ي(ī) in ‘āmmīyah, and similarly the second and third plural conjugations ون (ūn) in fuṣḥá to وا(ū) in ‘āmmīyah. Additionally, the imperfect verb employs the بـ (b) prefix in all conjugations, as in باروح (bārūḥ, ‘I go/am going’).

- Perfect verb conjugation: is largely similar with some minor variations of internal vowels and omission of final vowels except for the second person feminine singular (فَعَلتِ).

- Imperative verb conjugation: is again largely similar, with the minor differences of retaining the long vowel in hollow verbs as in قُل – قول and using long ي for defective verbs as in ادعي – اصحي – صلّي

Noun and verb negation

Nouns, adjectives and adverbs in fuṣḥá are negated with the verb لَيسَ, (laysa, ‘to ‘not’ be') which is conjugated for the 12 personal pronouns, while in ‘āmmīyah nouns, adjectives and adverbs are simply negated with مش (mish, ‘not’). Verbs in fuṣḥá are negated using the negators لم / لا / لن + imperfect verb (with the negators carrying the tense: لم for the past tense, لا for the present tense, and لن for the future or ما + perfect verb tense). In ‘āmmīyah the imperfect and future tense verbs are negated using مش while the perfect verb is negated by adding the ما prefix and ش suffix, along with a ‘helping vowel’ if this results in a 3-consonant cluster, as in:

كَتَبت (katabt, ‘I/you (m.) wrote’) -> ماكَتَبتِش (makatabtish, ‘I/you (m.) did not write’)

The imperfect verb can also take this form of negation, as in:

باكتب (baktib, ‘I write/am writing) ->

ماباكتبش / مش باكتب (mabaktibsh/mish baktib, ‘I do not write/am not writing’)

Future tense marker

While both fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah use a future tense marker + imperfect verb to indicate future tense, and both use a single letter prefix, in fuṣḥá this single prefix is the letter سـ /s/ + imperfect verb, while in ‘āmmīyah it is the letter هـ or حـ /h/ + imperfect verb. Additionally, fuṣḥá has another future tense marker, the word سوف + imperfect verb, which is not used in āmmīyah.

Verb forms

Although the verb forms are largely similar in form and function in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, Form IV isn’t used in ‘āmmīyah and some minor variation occurs in the vowelling, as shown in the table below:

Table 11: Verb forms in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah

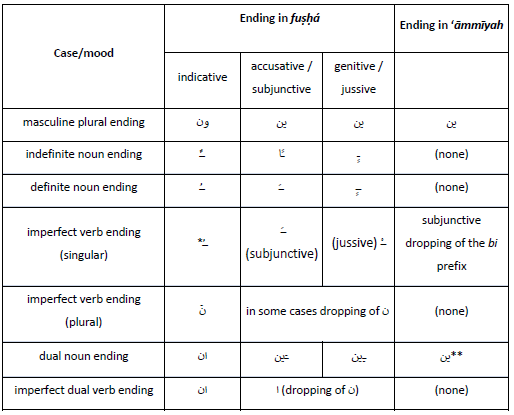

Case and mood inflections (indicative, accusative, genitive and jussive)

We find these mostly absent in ‘āmmīyah, which can explain to some extent the description of ‘āmmīyah as being a ‘simplified’ form of fuṣḥá. However, we do find the b+ prefix added to ‘āmmīyah imperfect verbs, but not in fuṣḥá. Further, the b+ suffix is dropped in the subjunctive mood in ‘āmmīyah. Some examples of variation between case and mood inflections are given in the table below:

Table 12: Examples of case and mood inflections absent in ‘āmmīyah

* Or ــَ (fatḥa) for 2nd person singular feminine ending (ينَ)

** Pronounced as /e:n/ (see Table 2 above)

Number-noun agreement

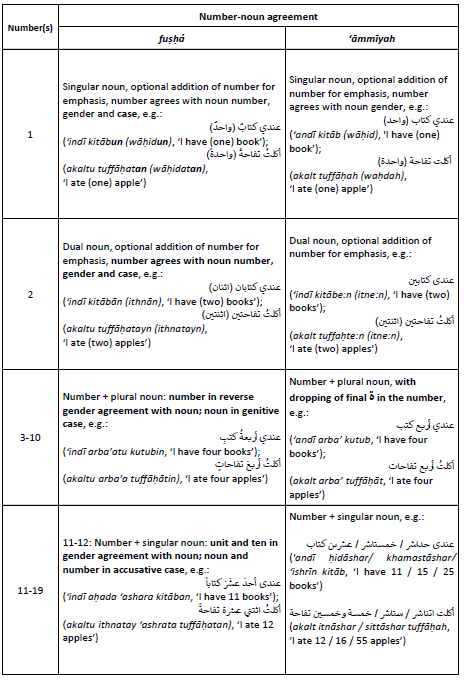

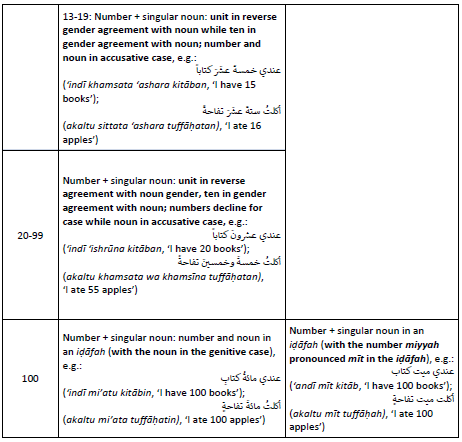

While the numbers themselves remain largely similar between fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, with some phonetic variation in ‘āmmīyah; fuṣḥá has notoriously complicated number-noun agreement rules, which are somewhat simplified in ‘āmmīyah. The table below summarises the agreement rules for each, with differences between them highlighted in bold.

Table 13: Summary number-noun agreement rules for numbers 1-100

Interrogatives

These are different lexical items in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah, although in many cases it is merely a case of phonological variation, as shown in Table 14 below:

| Fuṣḥá | ‘āmmīyah | Meaning in English |

| مَن (man) | مين (mīn) | Who |

| ما (mā) + noun | إيه (e:h) | What |

| ماذا (mādha) + verb | ||

| لِماذا (limādhā) | ليه (le:h) | Why |

| أينَ (ayna) | فين (fe:n) | Where |

| مِن أين (min ayna) | مِنين (mine:n) | Where from |

| مَتى (matá) | إمتى (imtá) | When |

| كيف (kayfa) | إزاي (izzāy) | How |

| كَم (kam) | كام (kām) | How many |

| بِكَم (bi-kam) | بِكام (bi-kām) | How much (cost) |

| هل (hal) | (none, although هل (hal) is used for emphasis/elevation) | Do/does/did |

Table 14: Interrogatives in fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah

In terms of syntactic variation, interrogatives in fuṣḥá are placed at the beginning of the question, whereas in ‘āmmīyah the syntax is more flexible and the interrogatives may be placed at the beginning of the question or after the noun, as in سامي فين؟ (‘Sami [is] where?’) for example.

Concluding remarks

Since the description of Arabic as a diglossic language by Ferguson (1959a), much attention has been paid to investigating the Arabic sociolinguistic situation. In particular, studies have focused on the specific features of Modern Standard Arabic known as fuṣḥá, and the spoken Egyptian (Cairene) dialect known as ‘āmmīyah, albeit treating them as separate entities. Since Badawi’s (1973) identification of Educated Spoken Arabic, several studies have attempted to define this language form and the variation that exists within it, such as (El-Hassan, 1977, 1978; Meiseles, 1980; and Elgibali, 1985) and some have investigated the use of code-switching within it (Eid, 1988; Bassiouney, 2006; Mejdell, 2011-12). Until recently, there has been an assumption that variation exists in speaking with no mention of variation in writing. This is true of most languages generally and not just for Arabic, as confirmed in Sebba et al. (2012). The advent of the internet and in particular social media, has led to an increase in visible variation in Arabic writing, and in turn an interest from sociolinguistic researchers in this phenomenon (Ibrahim, 2010; Doss and Davies, 2013; Kosoff, 2014; and Hoigilt and Mejdell, 2017).

With the increased visibility of variation in Arabic writing, it is imperative perhaps now more than ever, to understand the sociolinguistic situation and frame the discussion around variation in terms of both writing as well as speaking. In fact, Crystal (2006) identifies the internet as a fourth medium for language after spoken, written and sign language, worthy of study in its own right. This paper is part of a wider study that aims to develop a theoretical framework for the analysis of Arabic writing across time, genre and medium. This paper starts from the premise that both fuṣḥá and ‘āmmīyah are part of the same language and that their similarities are greater than their differences. As such, it treats the variation between these two forms as a subset of the language as a whole, worthy of discussion and analysis in order to aid further studies of the variation and mixing that occurs within the wider Arabic language. This study has compared fuṣḥá with Egyptian (Cairene) Arabic, identifying the levels of variation that exists between them and presenting these visually as a pyramid of three levels: Phonological, Lexical and Grammatical (including syntactic and morphological). The aim of presenting the variation in this way is to aid researchers working on variation in identifying the degree to which variation is present and in turn its significance. Moreover, studies of variation in writing such as Mejdell (2014), can use this classification system to determine exactly how variation is achieved by analysing which features from which level/s are employed. It is hoped that the classification tool can be added to, developed and further refined in future studies as well.

Another clear area for further study is the application of this paper’s classification of variation to other dialects and varieties of Arabic, in order to build up a clearer, more systematic and comprehensive view of the contemporary Arabic language situation. Previously Ferguson (1959b) has noted that similarities do exist between the various dialects, and understanding the degree of similarity and variation between them can help us rediscover the techniques used by native speakers such as classicising and levelling (Blanc, 1960) and hybridisation (Abu-Melhim, 1992) which raises to a high extent their mutual intelligibility (Ezzat, 1974). This especially since more recent studies of cross-dialectal communication have shown that MSA use in cross-dialectal situations has decreased in recent decades, with more participants than previously observed using more of their local dialect to communicate in cross-dialectal situations, with a high level of mutual intelligibility (Soliman (2014). In order to understand the techniques employed by native speakers in cross-dialectal situations, as well as to inform our teaching of Arabic as a foreign language, it is imperative to begin to understand variation in Arabic in a systematic and comprehensive way, which this study offers a tool for achieving.

Address for correspondence: smk58@cam.ac.uk

References

Abdel-Jawad, H. 1981. Lexical and phonological variation in spoken Arabic in Amman. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Abdel-Malek, Z. 1972a. The closed-list classes of colloquial Egyptian Arabic. Paris: Mouton.

Abdel-Malek, Z. N. 1972b. The Influence of diglossia on the Novels of Yuusif al-Sibaaʿi. Journal of Arabic Literature. 3, pp. 132-141.

Abdel-Massih, E. T., Abdel-Malek, Z. N., Badawi, E. M. and McCarus, E. N. 1979. A comprehensive study of Egyptian Arabic. Volume three, a reference grammar of Egyptian Arabic. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Center for Near Eastern and North African Studies, University of Michigan.

Abu-Melhim, Abdel-Rahman Husni. 1992. Communication across Arabic dialects: code-switching and linguistic accommodation in informal conversational interactions. Ph.D. thesis, Texas A&M University.

Badawi, El-Said. 1973. Mustawayat al-arabiyya l-mu’assira fi misr. Cairo: Dar al-ma’arif.

Bassiouney, R. 2013. Arabic sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bassiouney, R. 2006. Functions of code-switching in Egypt: evidence from Monologues. Leiden: Boston.

Blanc, H. 1960. Stylistic variations in spoken Arabic: a sample of interdialectal educated conversation. In: Ferguson, C.A. ed. Contributions to Arabic linguistics. Cambridge: Harvard University, pp.81-156.

Cowell, M. 2005. A reference grammar of Syrian Arabic. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Crystal, D. 2006. Language and the internet. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doss, M. and Davies, H. 2013. Al-‘ mmīyah al-Miṣrīyah al-Maktūbah: Mukhtārāt min 1401 ilá 2009. Al-Qāhirah: al-Hay’ah al-Miṣrīyah al-‘āmmah lil-Kutub.

Eid, M. 1988. Principles for code-switching between Standard and Egyptian Arabic. In Al-‘Arabiyya. 21(1/2), 51-79.

Eid, M. 1982. The non-randomness of diglossic variation. Glossa. 16(1), pp.54-84.

Elgibali, A. 1985. Towards a sociolinguistic analysis of language variation in Arabic: Cairene and Kuwaiti dialects. PhD thesis, University of Pittsburgh.

El-Hassan, S. A. 1978. Variation in the demonstrative system on educated spoken Arabic. Archivum Linguisticum. 9(1), pp.32-57.

El-Hassan, S. A. 1977. Educated spoken Arabic in Egypt and the Levant: a critical review of diglossia and related concepts. Archivum Linguisticum. 8(2), pp.112-132.

Ezzat, A. G. E. 1974. Intelligibility among Arabic dialects. Beirut: Beirut Arab University.

Ferguson, C. 1959. Diglossia. Word. 15, pp.325-340.

Ferguson, C. 1959b. The Arabic Koine. Language. 35(4), pp.616-630.

Gadalla, H. 2000. Comparative morphology of standard and Egyptian Arabic. Muenchen: Lincom Europa.

Harrell, R. 1957. The phonology of colloquial Egyptian Arabic. American Council of Learned Societies. Probgram in Oriental Languages. Publications. Series B: Aids, no. 9. New York: American Council of Learned Societies.

Hoigilt, J., and Mejdell, G. (eds). 2017. The politics of written language in the Arab world: writing change. Studies in Semitic languages and linguistics 90. Leiden: Brill.

Holes, C. 1990. Gulf Arabic. Croom Helm descriptive grammars. London: Routledge.

Ibrahim, Z. 2010. Cases of written code-switching in Egyptian opposition newspapers. In: Bassiouney, R. ed. Arabic and the media: Linguistic analyses and applications. Leiden: Brill, 23-45.

Khalafallah, A.A. 1969. A descriptive grammar of Saidi Egyptian colloquial Arabic. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

Kosoff, Z. 2014. Code-switching in Egyptian Arabic: a sociolinguistic analysis of Twitter. Al-‘Arabiyya. 47, pp. 83-99.

Meiseles, G. 1980. Educated spoken Arabic and the Arabic language continuum. Archivum Linguisticum 11(2), pp.118-43.

Mejdell, G. 2014. Strategic bivalency in written ‘mixed style’? A reading of Ibrahīm ʿĪsā in Al-Dustūr. In: Durand, O., Langone, A. D. and Mion, G. (eds). Alf Lahga Wa Lahga: Proceedings of the 9th Aida Conference.

Münster: Lit Verlag, pp.273-278.

Mejdell, G. 2011-12. Diglossia, code-switching, style variation and congruence: notions for analysing mixed Arabic. Al-‘Arabiyyah. 44-45, pp.29-39.

Mejdell, G. 2006. Mixed styles in spoken Arabic in Egypt: somewhere between order and chaos. Leiden: Brill.

Mitchell, T.F. 1978. An introduction to Egyptian colloquial Arabic. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mitchell, T.F. and El-Hassan, S. 1994. Modality, mood and aspect in spoken Arabic: with special attention to Egypt and the Levant. London: Kegan Paul International.

Norlin, K. 1987. A phonetic study of emphasis and vowels in Egyptian Arabic. Lund University Department of Linguistics. General linguistics, Phonetics, Working paper 30. Lund: Department of Linguistics and Phonetics.

Sebba, M., Mahootian, S., and Jonsson, C. Language mixing and code-switching in writing: approaches to mixed-language written discourse. Routledge critical studies in multilingualism 2, pp. 271—296.

Soliman, R. K. 2014. Arabic cross-dialectal conversations with implications for the teaching of Arabic as a second language. Ph.D. thesis, University of Leeds.

Willmore, J. 1927. Handbook of spoken Egyptian Arabic comprising a short grammar and an English Arabic vocabulary of current words and phrases. 3rd ed. enl. and rev. ed. London: David Nutt.

Wise, H. 1975. A transformational grammar of spoken Egyptian Arabic. Oxford: Philological Society, Great Britain.

Woidich, M. and Zack, L. 2009. The g/ǧ-question in Egyptian Arabic revisited. In: Al-Wer , E. and de Jong R. (eds.). Arabic dialectology: in Honour of Clive Holes on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday. Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill, pp.41–60.

Woolard, K. and Genovese, E. 2007. Strategic bivalency in Latin and Spanish in early modern Spain. Language in Society. 36(4), pp.487-509.

Woolard, K. 1999. Simultaneity and bivalency as strategies in bilingualism. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 8(1), pp.3-29.

Zribi, I., Boujelbane, R., Masmoudi, A., Ellouze, M. Belguith, L., and Habash, N. 2014. A Conventional Orthography for Tunisian Arabic. The Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14), May 2014. [Online]. [Accessed 5 April 2020]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270568583_A_Conventional_Orthography_for_Tunisian_Arabic

APPENDIX: Transliteration Scheme

The Transliteration scheme used in this study is the Library of Congress Romanisation scheme for Arabic[2], copied verbatim in Table A1 below. For writers with Standard English forms, e.g. ‘Yusuf Idris’, these forms are used, rather than strict transliterations. For transliteration of ‘āmmīyah terms, the phoneme /g/ is used for ج and for the pronunciation of the diphthongs /aw/ and /ay/ in ‘āmmīyah the IPA symbols /o:/ and /e:/ are used (see Table A1 below). In transliterations of ‘āmmīyah, some adaptations have been made, such as using wi- for the connective و instead of wa- and il for the definite article الـ rather than al.

| Letters of the alphabet | Romanisation |

| ا | omit |

| ب | b |

| ت | t |

| ث | th |

| ج | j |

| ح | ḥ |

| خ | kh |

| د | d |

| ذ | dh |

| ر | r |

| ز | z |

| س | s |

| ش | sh |

| ص | ṣ |

| ض | ḍ |

| ط | ṭ |

| ظ | ẓ |

| ع | ‘ |

| غ | gh |

| ف | f |

| ق | q |

| ك | k |

| ل | l |

| م | m |

| ن | n |

| هـ ، ة | h |

| و | w |

| ي | y |

| Vowels and Diphthongs | Romanisation |

| ــَ | a |

| ــُ | u |

| ــِ | i |

| ــَا | ā |

| ــَى | á |

| ــُو | ū |

| ــِي | ī |

| ــَوْ | aw (IPA /o:/ in ‘āmmīyah) |

| ــَيْ | ay (IPA /e:/ in ‘āmmīyah) |

Table A1: Library of Congress Romanisation scheme for Arabic

[1] from Adapted http://sites.middlebury.edu/arabicsociolinguistics/files/2013/02/class5_phonetics_consonants.pdf

[2] https://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/arabic.pdf