Arabic heritage students and their language-learning experiences. Limits and highlights

Marco Aurelio Golfetto, Ph.D., Department of Language and Cultural Mediation, Università degli Studi, Milan (Italy)

ABSTRACT

The presence of Arabic heritage students in classroom poses challenges especially in those language-teaching contexts where mainly traditional approaches are in use. This study deals with heritage learners’ (HLs) language education, the methods of teaching/assessing the students are faced with in their career and their success rate. In the first part of the article I focus on the definition of HLs across language and cultural issues based on literature. In the findings session, I analyse the specific situation of a group of HLs who study Arabic in Milan (Italy), by exploring aspects of their secondary and university language instruction. I collect statistic information through quantitative research by using a structured questionnaire. I later compare the data gathered about the HLs’ instruction with that of their non-heritage colleagues by using inferential statistics. For this purpose, I employ parametrical and non-parametrical tests. In the subsequent discussion session, I delve into the surveyed HLs’ language learning experience also in the light of socio-economic conditions and teaching/assessing methods, and by focussing on the importance of early literacy in Arabic for their linguistic success. I finally draw conclusions on possible convergent needs of heritage and non-heritage learners (NHLs) and the potential of the formers’ presence in mixed classes rather than the advantages of “forking out” the courses.

KEYWORDS: teaching of Arabic, heritage learners, language learning tracks, formalistic approach, class organisation

INTRODUCTION: PERSPECTIVES ON HERITAGE

After the initial reflection started in the 1970s when a rage of different labels was still in use, scholars have opted for two different perspectives in the definition of heritage learners (HLs), involving either linguistic or cultural/identity features. A classical definition of the first kind is provided by Valdés (2001, p.38), who focuses on the - at least relative - bilingual nature of the HL: he/she is someone who is raised in a home where a language other than English (meaning the local majority language) is spoken and can speak, or at least understand, this other language in addition to English. Although Valdés already shows interest for these learners’ sensitive orientation toward their heritage community, their sense of membership rather than their actual proficiency is more central in other studies, such as Van Deusen-Scholl’s (2003, p.221): HLs are a heterogeneous group that perceives having a cultural connection to a specific language, regardless of their being fluent native speakers or non-speakers of that language. In line with this perspective, heritage students can differ from one to another from various points of view, such as their “degree of affiliation with ethnic, cultural, and/or religious identity; level of proficiency; experience in country or with culture” (Lee, 2005, p.561).

A continuum ranging from non-heritage learners (NHLs), who have neither proficiency nor ethnic affiliation, to HLs, who have both linguistic knowledge and ethnic, religious or cultural identity related to the heritage language, can thus be found in any setting of foreign language (FL) teaching. The group of ethnic, cultural, or religious HLs with no language proficiency stands between the two other groups, and their collocation in the proximity of each of these ends can greatly vary according to their learning, affective, social and identity motivations, needs and goals, in a number of different scholars’ disciplinary perspectives or with respect to some peculiarities of the target language. For example, in her early study about Japanese HLs, Kondo-Brown (2005) argues that students in whose family Japanese is spoken only by distant members can be better combined with NHLs and must be tracked separately from students with a Japanese-speaking parent, who were already somewhat proficient in the language because they had lived in Japan or studied it at school. On the contrary, Husseinali (2006) gathers in the same group all the religious HLs of Arabic, i.e. those who study Arabic because of their Islamic belief, independently from their actual descent and initial proficiency. Accordingly, provided their sense of belonging and their motivational orientations, they can be safely collected in the same class.

A fully comprehensive model for HLs in its wide meaning is Carreira’s (2004), whose study offers a dual approach to these learners’ identity and needs. Moving from Fishman’s (2001) initial observation that the term “heritage language” in the US is used to refer to immigrant, indigenous and colonial languages, and that the corresponding human environments are characterized by different historical, social, linguistic and demographic realities, Carreira (2004, p.1) points out that the various definitions given can be valid for specific communities and linguistic tasks, but they are not able to embrace all and only such individuals that fall under the label of HLs. A four-fold model is thus proposed that takes into account different possibilities: 1. personal participation to the ethnic community, desire of full or deeper connection with it and transmission of its values from inside; 2. family or ethnic, although not personal or direct, background and desire to learn about the ways of the community from outside and in search of identity; 3. possession of language proficiency whose degree is variable according to the situations and hardly defined in previous studies; 4. family connection to and self-perception of heritage identity despite insufficient fluency, that brings external (formal educational or societal) negation of the status of such an identity. This wide range of considerations seeks for an explanatory adequacy: heritage students are not a homogeneous cluster of learners, but a collection of different types of learners who share the characteristic of having identity and linguistic needs that relate to their family background. These needs arise from having had insufficient exposure to their HL [heritage language] and HC [heritage culture] during their formative years. Satisfying these needs provides a primary impetus for pursuing language learning. (Carreira, 2004, p.21)

Research on the HLs further blossomed through the first decade of 2000s, with a number of essays on their nature, identity, motivations and literacy (see in particular Peyton, Ranard and McGinnis, 2001). Experimental and survey-based research has also tried to cast further lights on their proficiency, language levels, linguistic abilities, and degree of acquisition, confronting HLs with L2L and NHLs (see for example Montrul 2010, 2011 and 2013). Pedagogical theories have been developed that focus on the HLs’ characteristics in order to plan specific frameworks and curricula for different language areas (see Valdés, 2014; Valdés and Parra, 2018). Ground research in different teaching contexts has also widely confirmed its meaningfulness in highlighting HLs’ learning preferences and suggesting possible directions for teaching tracks.

METHODS: THE RESEARCH SETTING

This article aims at analysing the language learning experience of a group of heritage students majoring in Arabic at the Univeristà degli Studi of Milan (Italy).[1] The surveyed group consisted in 40 students enrolled at MA and BA degree courses in Language and Cultural Mediation who accounted for 18.8% of the total subjects attending Arabic classes. Heritage learners are presently meant as students of Arabic who declared that they spoke only Arabic or both Italian and Arabic in their family. 50% of these students were born in Arab countries (Morocco (8), Egypt (7), Tunisia (2), Kuwait (2), Lebanon (1)). One student was born in Chad, whereas the others were all born in Italy. Their ages ranged from 19 to 44.

The questionnaire was administered to HLs and NHLs in the first semester of Academic Year 2018-19 in repeated sessions during regular classes. This study is based on the final array of questions investigating the participants’ learning history: attended high school, curricular study of other FLs, second FL studied at university, attained FL certifications, estimated or objective achieved levels of proficiency in Arabic and so forth, in order to out sketch their language learning pathways.[2]

After the data were encoded, descriptive statistics were used to collect quantitative information about the group, whereas inferential statistics were used to compare information gathered about the HLs with that of their non-heritage peers. Parametrical and non-parametrical tests (such as Mann Whitney tests and Fisher’s exact tests) were used for this purpose.

RESULTS: HLS’ EDUCATION AND PERFORMANCE

High school instruction can have a deep impact on the academic attainments and professional career of subject students in Italy. It can be relevant for their education and profile from different points of view, and mainly in three ways: the cultural stimuli supplied, the degree to which they are used to the study load, and their language education record (as regards both the native language and the foreign one/s).

Secondary education

HLs were surveyed as regards their secondary education. Their attendance of high schools could be rated as of a medium level. In most cases, they were enrolled at secondary schools that would allow them to enter the job market even without pursuing a university degree.

Only 7.5% of them had access to high schools that are best evaluated, such as Liberal Arts, Sciences, or Social Sciences high schools. These schools are appraised in the Italian education system because they offer classical humanistic education, train students by means of an intense intellectual workload and help them develop critical awareness. They mostly use a formalistic approach to teach, by intensively insisting on the importance of linguistic analysis and literary studies, but they are not the best option for modern foreign language education, as students are taught only one language (usually English), in addition to classical ones such as Latin and more rarely ancient Greek.

As for the bulk of surveyed HLs, 42.5% attended a Foreign Languages high school or a Tourism high school. These schools differ from one to another in the humanistic or vocational imprint they offer. However, they are similar from other perspectives. For instance, they can directly lead to employment if students decide to end their education after 5 years of attendance, but they also allow students who decide to pursue university studies afterwards to adequately study a large span of subjects. A major common ground for these schools is obviously language education, which is mainly taught with the communicative approach. Attending students are expected to learn 3 FLs, with the addition of Latin in the case of Foreign Languages high school. Learners are also often encouraged to enhance their language skills by achieving international FL certifications.

A relevant percentage of HLs (27.5%, the highest in absolute terms) attended schools with basic technical or vocational curricula. These schools guide students to quickly attain a job right after achieving their high school diploma and are less focused on both intellectual and language stimulation. In particular, students are taught one (or rarely two) FLs, but the achievement of international certification is often the result of personal commitment rather than a standard requirement or practice.

Finally, another 10% of the HLs attended other schools - usually less appraised - that were not focused on FLs, whereas 12.5% of the respondents came to Italy after attending a high school in their country of birth.[3]

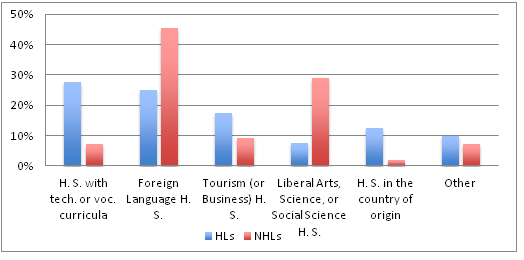

Table 1 and Figure 1 show the secondary schools that the respondents attended, comparing the percentages of HLs and NHLs. Without considering the subjects whose high school education took place abroad, the distribution of the two groups revealed a statistically significant difference (p .0005, using the Fisher’s exact test), with a higher number of NHLs attending better appraised schools.

| HLs | NHLs | |

| Liberal Arts, Science, or Social Sciences high school | 3 (7.5%) | 48 (29.1%) |

| Foreign Language high school | 10 (25%) | 75 (45.5%) |

| Tourism (or Business) high school | 7 (17.5%) | 15 (9.1%) |

| High school with technical or vocational curricula | 11 (27.5%) | 12 (7.3%) |

| Other high school | 4 (10%) | 12 (7.3%) |

| High school in the country of origin | 5 (12.5%) | 3 (1.8%) |

| Total | 40 (100%) | 165 (100%) |

Table 1: High schools attended by HLs and NHLs (frequency)

Figure 1: High schools attended by HLs and NHLs (percentage)

Language Education

Most of the surveyed HLs (67.5%) claimed that they had learned 2 or 3 FLs at their high school. Extreme situations, i.e. HLs who studied only one FL and those who studied 4 or more FLs[4], were less frequent and approximately correspondent in number (17.5% for the former case and 15% for the latter). Since they were currently attending a university degree in which language was central to the curriculum, this result can be again classified as of an average level. Students were exposed to a good amount of FL input, which, in most cases, can be estimated in at least 5 to 11 contact hours per week during their secondary career.

Given the little range of FLs that are usually taught in class at high school, the HLs’ choice was limited to the most common European languages: English, French, Spanish, and - more rarely - German. No - or a negligible - choice was made in favour of FLs using non-Latin alphabets (unless the students had attended high schools abroad). Only a small minority of the HLs studied ancient Greek and they rarely learned languages with noun inflection. See Table 2 for the FLs studied at high schools.

As for the languages studied at university, these were in line with what one may expect from the previous figure. Indeed, in most cases the other required language that was chosen, along with Arabic, was English (55%), whereas the second studied foreign language was French (25%). Beside their relevance on the international scene, these were also the two languages that traditionally played a major political role in the Middle East and North Africa. The “cultural”, rather than professional, nature of this choice is highlighted by the fact that a language such as German, which is usually perceived in Italy as very promising in occupational terms, was studied by only 2.5% of the students, i.e. even less frequently than Chinese (7.5%), Spanish and Japanese (both 5%).

| Frequency | % | |

| English | 38 | 95 |

| French | 19 | 47.5 |

| Spanish | 13 | 32.5 |

| German | 8 | 20 |

| Arabic | 8 | 20 |

| Latin/Greek | 5 | 12.5 |

| Russian | 1 | 2.5 |

| Chinese | 0 | 0 |

| Hebrew | 0 | 0 |

| Japanese | 0 | 0 |

Table 2: Languages studied at high school (frequency and percentage out of the total number of 40 HLs)

An area in which the HLs provided surprising results was that of international foreign language certifications. Although 37.5% of the respondents admitted that they had never taken the opportunity to sit for this kind of testing, 55% claimed that they had achieved 1 or 2 certifications in any of the languages they had studied, whereas 7.5% obtained 3 or more. However disproportionate the results might appear at first sight (see Table 3), inferential statistics revealed that the difference between the two groups of HLs and NHLs was not significant in this regard (p .0625). On the contrary, the Fisher’s exact test highlighted a statistically significant difference (p .0005) among the number of FL certifications that had been achieved according to different high schools, with a disadvantage for those schools that were most often attended by the HLs. This is to say that HLs were as effective in achieving international certifications as their NH colleagues, and, noticeably, they did so partially despite the secondary education they received, which tended to put them at a disadvantage in this respect. This apparent disproportion between poorly supporting schooling and the students’ success rate in achieving FL certifications is even more indicative of the HLs’ awareness of the importance of the international dimension of their professional profile.

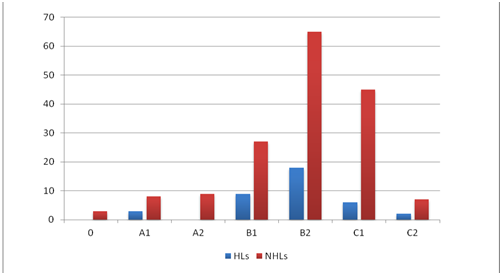

Achievement in language education was also surveyed. In general terms, the HLs’ language proficiency referred to the other requirement language was comparable to that of the NHLs. In response to the question about the language level they achieved in the second target language studied at university according to the CEFR descriptors, the HLs mainly located themselves in the B1-B2 range. Despite an apparent discrepancy at the highest level, the bell-shaped curve resulted comparable, and inferential statistics did not highlight significant differences in this respect (p .1774). See Figure 2.

| HLs | NHLs | |

| No certification | 15 (37.5%) | 48 (29%) |

| 1 or 2 certif. | 22 (55%) | 73 (44.5%) |

| 3 or more certif. | 3 (7.5%) | 42 (25.5%) |

| No response | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) |

| Total | 40 (100%) | 165 (100%) |

Table 3: FL certifications achieved by HLs and NHLs

Figure 2: Proficiency level achieved by HLs and NHLs in the other requirement language (frequency)

A very different situation was that concerning the HLs’ proficiency level in Arabic, at least according to the students’ self-evaluation. HLs and NHLs were requested to try and grade their level in Arabic according to the CEFR guidelines. Although the implementation of the CEFR for Arabic is still on its way,[5] the question was proposed in order to try and survey the students’ self-perception as native speakers of Arabic. The distribution of the responses was quite telling: 41% of the HLs stated to be at a mother tongue level in year 1 (the questionnaire was handed out at the very beginning of their academic career), but this percentage dramatically dropped in the following years, eventually becoming naught at MA level. Somehow, during their academic career, the students had to go through a kind of negative iktishāf about their linguistic identity.[6] On the other side, some rather regular proficiency enhancement was also perceived, that offset the previous disappointing figure. See the arithmetic values in Table 4. The limited number of surveyed subjects and the actual subjectivity of their perception however should lead to prudence in the interpretation of these results.

| BA1 | BA2 | BA3 | MA1 | MA2 | Total | |

| A0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| A1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| A2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| B1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| B2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 10 |

| C1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| C2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Native | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Total | 12 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 40 |

Table 4: HLs’ self-estimated proficiency level of Arabic per academic standing (frequency)

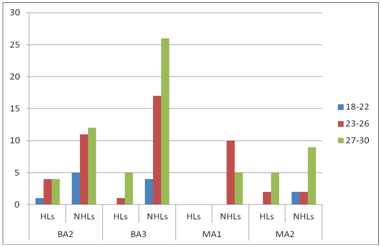

Alongside that of the HLs, also the NHLs’ self-perception of proficiency in Arabic was surveyed. According to inferential statistical tests, the difference of self-perceived proficiency between the two groups was significant (p .0005): as was obvious, HLs perceived themselves as more proficient in “Arabic”, whatever the interpretation of this word might have been. Going further into this, a gap appeared when the difference in the self-evaluation of the two groups was contrasted with the difference in the grades the HLs and NHLs got in their exams. The average scores achieved by the HLs were slightly higher than those achieved by NHLs, but the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (p .6977). See Table 5 and Figure 3 for details. In a way, the HLs’ higher expectations about their proficiency were not supported by their university scores.

| Grades | HLs | NHLs |

| 18-22 | 1 (4.5%) | 11 (11%) |

| 23-26 | 7 (32%) | 40 (39%) |

| 27-30 | 14 (63.5%) | 52 (50%) |

| TOT | 22 (100%) | 103 (100%) |

Table 5: Annual assessments of proficiency levels for Arabic (means and percentage)

Figure 3: Annual assessments of proficiency levels for Arabic (frequency)[7]

DISCUSSION: CRITICAL ISSUES OF THE HLS’ EDUCATION

A set of motives different in nature led the HLs to study Arabic. Their fascination for the heritage language and familiarity with the culture were just two prompting factors, and the initial motivation was further implemented by identity motives and professional orientations. Foreknowledge, previous acquaintance with the language, and a high rate of motivation should foretell these students’ success in learning Arabic. However, the survey pointed to lights and shadows of their linguistic education. HLs proved to be able to overcome predictable initial disadvantage in education aligning themselves to NHLs in most situations: exemplar is the case of FL certifications. Nevertheless, despite being recognized as at least bilingual subjects, they reached a moderate degree of proficiency (mainly B1-B2) in their second required language and achieved average results in MSA that were not statistically different from those of their NH peers. [8] In short, their performance appeared somehow more modest than it could potentially be, especially at entry and lower levels. Concurrent causes might be at the base of this.

The first and most basic one can be connected to the limits of the present survey: as attendance of classes is not compulsory, the total population of students of Arabic might possibly be slightly more extended than that surveyed. HLs who already had high levels of proficiency in Arabic simply might have been overlooked, because they did not attend any of their classes. This anyway is a quite remote possibility.

A second and more feasible reason can consist in the learners’ socio-economic environment, which has far and long been considered a relevant factor affecting schooling and educational achievement (see for example Wagner, 1993, p.107; Sehlaoui, 2008, p.284). As opposed to the most recent wave of immigration from Arabic countries surveyed in the US (see Bale, 2010, pp.133-134), immigrants in Italy usually live in more modest conditions. The good scored percentage of respondents selecting “both Arabic and Italian” as family languages might be indicative of a good rate of integration into the local society, especially if it is in the form of mixed marriages. Nevertheless, the medians of their age were found higher than those of their NH peers for all years at BA level: higher average age in relation to the academic standing is an indicator of the additional difficulties they had to face in their instruction. Far from being only a theoretical issue, the HLs’ uneasy conditions and poorer secondary schooling resulted in a number of potential limits:

- weaker education, less focused on foreign languages and basically oriented to immediate job training with more modest vocational and professional expectations.

- greater difficulty to access information about the local education opportunities: 25% of the surveyed HLs admitted that one of the three most important reasons for which they chose the present degree course was being the only one offering classes of Arabic in their knowledge.

- less acquaintance with attentive language analysis: HLs were less sensitized to deep reflection on morph-syntactic structures and critical analysis of the language, either L2 or FLs. In a word, they were less exposed to the formalistic language teaching approach and thus potentially less effective when they were faced with it at university.

- no previous formal contact with languages using non-Latin alphabets and with other linguistic features that are recurrent in formal Arabic, such as for example the noun/adjective inflection. These features, although not attested in oral Arabic and dialects, are typically introduced at an early stage of the teaching of formal Arabic when the target students are non-natives. This confronts the HLs with an initial amount of difficulties that they are often not willing to cope with in the very beginning, thus quickly losing motivation in class activities.

A third and more relevant reason for the lower-than-expected language results was undoubtedly connected to previous insufficient literacy in Arabic: this is considered a usual feature for Arabic HLs and it involves not only the written domain of the language, but also its oral dimension. As pointed out by Zabarah (2016), HLs’ knowledge of their native dialect is often incomplete and their skills are still developing, being usually limited to family and daily context usage. Most frequently HLs lack written literacy in native tongue and, if this is present, it can be limited to the religious sphere. The specific surveyed situation confirmed that when previous literacy in Arabic took place, it was mainly provided by the close social environment. Arabic classes, in both their curricular and non-curricular form, are indeed extremely rare in Italian high schools at present, whereas Arabic weekend programs or masjid schools are quite exceptional and not infrequently contrasted due to political reasons. As a consequence, the surveyed HLs hardly had previous formal alphabetization in their mother tongue. Effects of this incomplete literacy in Arabic also exceed the proficiency in the sole target language. It was highlighted that bilingual learners academically outperform their monolingual peers when they are “literate in their native tongue”. As suggested, literacy - meaning “more than just the ability to read and write. It includes reading, writing, speaking, listening, viewing, and representing visually. It also includes computer literacy” (Sehlaoui, 2008, p.283) in a heritage language is in fact a crucial matter for acquiring L2, as it is for acquiring any FL in general. If literacy is incomplete in the heritage language, this will affect consequently the entire process of language acquisition. Thus, HLs should become adequately proficient in their actual native variety in order to acquire literacy in MSA in a more natural way.

Another issue that might be accounted as a further reason for the divergence between general expectations and HLs’ performance was possibly the focus of the teaching and testing methods used in class, that were not specifically modeled on both the HLs’ previous learning experience and their actual entry level of literacy. Given the secondary instruction received, HLs are less inclined than their peers to traditional and formalistic approaches in class. On the contrary, they are more suitable for a communicative approach, i.e. an approach that emphasises interaction as both the means and the goal of the study, and more firmly oriented to gaining quick, effective competence in the target language by focusing on oral and textual functional competence. As a matter of fact, although the teaching approach at university is increasingly evolving towards communicative patters, it is still oriented to literacy more than to oral proficiency, and the focus of the classes relies on MSA from the very beginning. Assessment is also consequently focused on the written and literary variety, and the attention paid to dialects is an exception rather than a standard. This makes the learning a less natural process for HLs, especially in the initial phase, and revolutionizes their linguistic identity in the long term.

Finally, it should be noticed that there is at least another reason that justifies the gap between expectations and linguistic performance at the assessment. Unsatisfactory results have been related to HLs’ misconceptions regarding their own language abilities (Zabarah, 2016). In this regard, HLs’ difficulties have been highlighted even in oral assessment (Albirini et al., 2011), where the students usually judge themselves more naturally and easily inclined to higher levels of proficiency. Literature and assessing results confirmed that incomplete proficiency in oral skills is also an eventuality for this kind of students. When attending courses of Arabic, HLs may overlook the existing language gap between the variety they already know and MSA. They are obviously not unaware of the existence of diglossia and variation, but they partially lack awareness of the demanding task and real workload they are going to face. This explains faster demotivation when they see their expectations frustrated, despite their initial motivation is as intense as – if not more intense than - that of NHLs. An educational agreement (that clarifies the students’ expected learning duties and rights) and educational curricula and settings more precisely designed around the target students’ needs could effectively help contain the attrition rate.

CONCLUSIONS: CLASS ORGANISATION OPPORTUNITIES

The findings of the present study have shown that HLs’ language achievements and performance can be affected, to a good extent, by the high school education they received. These effects persist at university level so that HLs developed peculiar methodological needs and expectations about the teaching of Arabic, especially because their literacy and previous exposition to the target language were limited. They need (and have right to) comparable - although not necessarily the same - conditions of leaning as NHLs, in terms of same potential of tools, stimulation and follow-up, as regards quality and appropriateness. An ultimate verdict on whether a separate track is recommended for HLs of Arabic or not falls beyond the aim of this paper. In fact, this study has highlighted elements that may support both positions and, in any case, the eventual decision of an independent track for Arabic HLs would depend on the number of HLs that request it and the availability of the necessary funding in the specific educational institution. In the case of Italy, this would be hardly possible at present.

As a whole, the idea of a separate academic track, at least in the initial stage of the career, is a well-established reality for many other languages, and “forking out” courses for HLs and NHLs is at times referred to also in the literature about Arabic (Huseinali, 2006, p.407; Temples, 2010, pp.124-125) as it expects to allow classes with more homogeneous profiles and learning needs, faster acquisition, and higher motivation and retention rates. Evidence from the education experiences presently surveyed confirmed that HLs can best learn when faced with approaches aimed at communicative models. In particular, oral skills should be mostly focused on in the initial phase of teaching. Traditional approaches, such as those centered on grammar and translation, might be more appraised for NHLs, due to their previous acquaintance with them in secondary education. Nevertheless, these approaches seem less convincing for HLs, as they make it more difficult to recall linguistic foreknowledge and fill the gap between mastered (or partially mastered) dialect and MSA.

On the other hand, the idea of possibly homogeneous HLs’ classes can be easily challenged for many reasons, such as their different initial degree of proficiency, native dialect, objectives, religious orientation, and so forth. Furthermore, as was previously expounded, HLs and NHLs may have partially communal learning difficulties in the very beginning of the track. Although HLs are clearly advantaged in the lexical and phonological domains, if they lack previous written literacy, some language features, such as the novelty of a non-Latin alphabet and declensions of nouns/adjectives, confront them and NHLs with the same problems. Not infrequently, also morphology and basic syntax remain a sensitive issue for most HLs, with difficulties that are actually shared by both groups.

To conclude, a number of advantages can instead be highlighted for mixed HLs-NHLs classes. In a mood for a growing appreciation for local variants of Arabic, HLs can become a useful resource in class for the teacher. The presence of heritage students allow teaching Arabic variation live, providing all the learners with the same authentic language experience they will soon find in real world. It allows the teacher to present the variation device in learners’ syllabuses from the very beginning, basing the linguistic acquisition on a more natural language, as recommended by the CEFR guidelines. If they are properly instructed in and aware of the strategies to use with their reservoir of knowledge (Carreira, 2004, p.16), HLs can also actively support the NHLs through peer tutoring, in simple dialogical and communicative settings or more complex language tasks. Curricular and methodological flexibility will be in any case essential.

Address for correspondence: marco.golfetto@unimi.it

REFERENCES

Albirini, A., Benmamoun, E., and Saadah, E. 2011. Grammatical features of Egyptian and Palestinian Arabic heritage speakers’ oral production. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 33, pp.273-303.

Badawi, al-S. M. Al-Thunā’iyya al-tarbawiyya wa-qaḍiyyiat al-ḥāfiz fī ta‘līm al-‘arabiyya li-abnā’ al-mahjar. Baḥth muqaddam ilà liqā’ Brūksil ḥawla ta‘līm al-‘arabiyya li-abnā’ al-muhājirīn al-‘arab yūnīū 1985. In: Badawi, al-S. M., and ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, M. Ḥ, ed. Buḥūth lughawiyya wa-tarbawiyya fī qaḍāyā al-‘arabiyya al-mu‘āṣira wa-mushkilātihā. Al-Qāhira: Dār al-salām li’l-ṭibāʻa wa’l-nashr wa’l-tawzīʻ wa’l-tarjama, 2015, pp.29-49.

Bale, J. 2010. Arabic as a heritage language in the United States. International Multilingual Research Journal. 4, pp.125-151.

Carreira, J. M. 2004. Seeking explanatory adequacy: A dual approach to the term “heritage language learner”. Heritage Language Journal. 2(1), pp.1-25.

Fishman, J. A. 2001. 300-plus years of heritage language education in the United States. In: Peyton, J. K., Ranard, D. A, and McGinnis. S. eds. Heritage languages in America: preserving a national resource. Long Beach: McHenry, pp.81-99.

Giolfo, M. and Salvaggio, F. 2017. Mastering Arabic variation: a common European framework of reference integrated model. Rome: Aracne Editrice.

Husseinali, G. 2006. Who is studying Arabic and why? A survey of Arabic students’ orientations at a major university. Foreign Language Annals. 39(3), pp.395-412.

Kondo-Brown, K. 2005. Differences in language skills: Heritage language learner subgroups and foreign language learners. The Modern Language Journal. 89(4), pp.563-581.

Lee, J. S. 2005. Through the learners’ eyes: Reconceptualizing the heritage and non-heritage learner of the less commonly taught languages. Foreign Language Annals. 38(4), pp.554-567.

Montrul, S. 2010. How similar are L2 learners and heritage speakers? Spanish clitics and word order. Applied Psycholinguistics. 31, pp.167-207.

Montrul, S. 2011. Morphological errors in Spanish second language learners and heritage speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 33(2), pp.155-161.

Montrul, S. 2013. How “native” are heritage speakers? Heritage Language Journal. 10(2), pp.153-177.

Peyton, J. K., Ranard, D. A, and McGinnis. S. eds. 2001. Heritage languages in America: preserving a national resource. Long Beach: McHenry.

Sehlaoui, A. S. 2008. Language learning, heritage, and literacy in the USA: The case of Arabic. Language, Culture and Curriculum. 21(3), pp.280-291.

Soliman, R. 2017. The implementation of the common european framework of reference for the teaching and learning of Arabic as a second language in higher education. In: Wahbah, K.M., Taha, Z.A., and England, L. eds. Handbook for Arabic language teaching professionals in the 21st century. Volume II. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp.118-137.

Temples, A. L. 2010. Heritage motivation, identity and the desire to learn Arabic in U.S. early adolescents. Journal of the National Council of Less Taught Languages. 9, pp.103-132.

Valdés, G. 2001. Heritage language students: Profiles and possibilities. In: Peyton, J. K., Ranard, D. A, and McGinnis. S. eds. Heritage languages in America: preserving a national resource. Long Beach: McHenry,, pp.41-49.

Valdés, G. 2014. Heritage language students. In: Wiley T. J., Peyton J. K., Christian D. et al. eds. Handbook of heritage, community, and Native American languages in the United States: research, policy, and educational practice. London: Routledge, pp.19-26.

Valdés, G. and Parra, M. L. 2018. Towards the development of an analytical framework for examining goals and pedagogical approaches in teaching language to heritage speakers. In: Potowski, K. ed. Routledge handbook of Spanish as a heritage language. London: Routledge, pp.301–330.

Van Deusen-Scholl, N. 2003. Toward a definition of heritage language: Sociopolitical and pedagogical considerations. Journal of Language, Identity § Education. 2, pp.211-230.

Wagner, D. A. Literacy, culture, and development: becoming literate in Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Wahba, K. M., Taha, Z. A., and England, L. eds. 2006. Handbook for Arabic Language teaching professionals in the 21st century. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wahba, K. M., Taha, Z. A., and England, L. eds. 2017. Handbook for Arabic Language teaching professionals in the 21st century. Volume II. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zabarah, H. 2016. College-level Arabic heritage learners: do they belong in separate classrooms? Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages. 18, pp.93-120.

APPENDIX

Section 3: Personal information and education

Q38: Your genre: M F

Q39: Your age: ___

Q40: Your Academic Standing: BA1 BA2 BA3 MA1 MA2

Q41: What language/s is/are spoken in your family: Italian Arabic Both (Italian and Arabic) Other (please, specify _____________)

Q42: What High school did you attend: Liberal Arts high school or Science high school Foreign Language high school Tourism or Business high school Social Science high school High school with technical or vocational curricula High school in the country of origin Other (please, specify _____________)

Q43: How many FLs did you study at High school: ___

Q44: What FLs did you study at High school: English German Spanish French Russian Arabic Latin and/or Ancient Greek Other (please, specify ___________)

Q45: What is your other requirement FL at university, beside Arabic: English French German Spanish Russian Chinese Japanese Other (please, specify ___________)

Q46: What level did you achieve in this other requirement language: Native A1 A2 B1 B2 C1 C2

Q47: How many FL certifications did you achieve: 0 1-2 3 or more

Q48: What is your average annual assessment for Arabic: No exams yet 18-22 23-26 27-30

Q49: What proficiency level do you expect to have achieved in Arabic (according to the CEFR framework)? Native A1 A2 B1 B2 C1 C2

Q50: […]

Q51: Why did you choose a degree course in Mediation: It offers a curriculum oriented to professions In order to study a European and a non-European language at the same time In order to study Law and Economics, beside FLs In order to study Arabic linguistics and Arabic literature In order to study the Arabic culture It was the only place I knew for studying Arabic

[1] All the attending students were required to major in two languages (beside Arabic, another European or non-European language) and the related cultures, and to study a range of professionally oriented subjects, in order to achieve graduation.

[2] The items of the final section of the administered questionnaire are given in the Appendix.

[3] It is debated whether immigrant students who graduated at a high school in the country of origin where the target language is officially in use can be considered HLs. The subjects of the present survey were considered as such, but the specificity of this subgroup could have been taken into consideration separately if the number of students had been more quantitatively relevant.

[4] Not all of these languages were studied to the same extent and depth: up to 3 FLs can be required for high school curriculum, but students can study optional languages in afternoon classes. This is usually the case in LCTLs.

[5] For two recent issues on the Common European Framework of Reference as applied to Arabic see Giolfo and Salvaggio (2017) and Soliman (2017).

[6] The drop may well occur because students already perceiving themselves as native speakers did not attend classes. But it is also possible that a newly acquired perception of distance between the native variant and Standard Arabic played a relevant role in this perception.

[7] BA1 was 0, as the students had not sat any exams yet.

[8] Specifically, in the surveyed setting the exam scores resulted from an average evaluation of the assessment of grammar and translation skills from/to MSA (where HLs traditionally find themselves in greater difficulty) and that of their dialogical skills, which was mostly shaped by teaching and assessing models aiming at proficiency (and thus should be more in line with the expected skills of native speakers). This latter part of the exams was again focussed mainly on MSA, but it also partially assessed other varieties (Egyptian or Moroccan dialects).